Ten-month-old Amir Hayden sits on his mother's lap inside a sound-proof booth at UCSF Benioff Children's Hospitals audiology clinic in Oakland, as audiologist Sarah Coulthurst, MS, takes him through a hearing test of different tones. He doesn't react.

Amir's mother, Alisa Ellingberg, already suspects something is wrong.

Amir has just recovered from bacterial meningitis, a potentially deadly infection that causes swelling around the brain and spine. Up to 35% of children who survive the illness are left with hearing loss, partly because the infection can result in damage to the inner ear's cochlea, the organ that carries sound to the auditory nerve and up to the brain.

"It kicked us into high gear," says Coulthurst, co-director of UCSF Benioff Oakland's cochlear implant team, of Amir's hearing test.

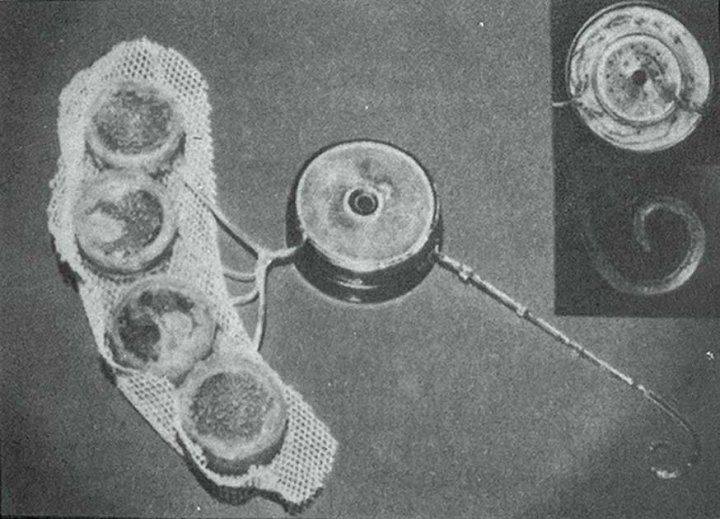

Her co-director, Dylan Chang, MD, PhD, UC San Francisco professor in residence and ears, nose and throat surgeon, quickly sees Amir and orders more scans as a multidisciplinary expert team assesses the boy. The scans confirm meningitis has left Amir deaf. Damage from the infection now risks entombing his cochlea nerve in a bony shell within days, permanently cutting off his only chance to perceive sound again with a surgically embedded device known as a cochlear implant. It's a race against time.

"We have to implant him on Monday," Coulthurst remembers Chang saying.

The team diagnoses and prepares Amir to receive a cochlear implant in each ear in just eight days - a hospital record.