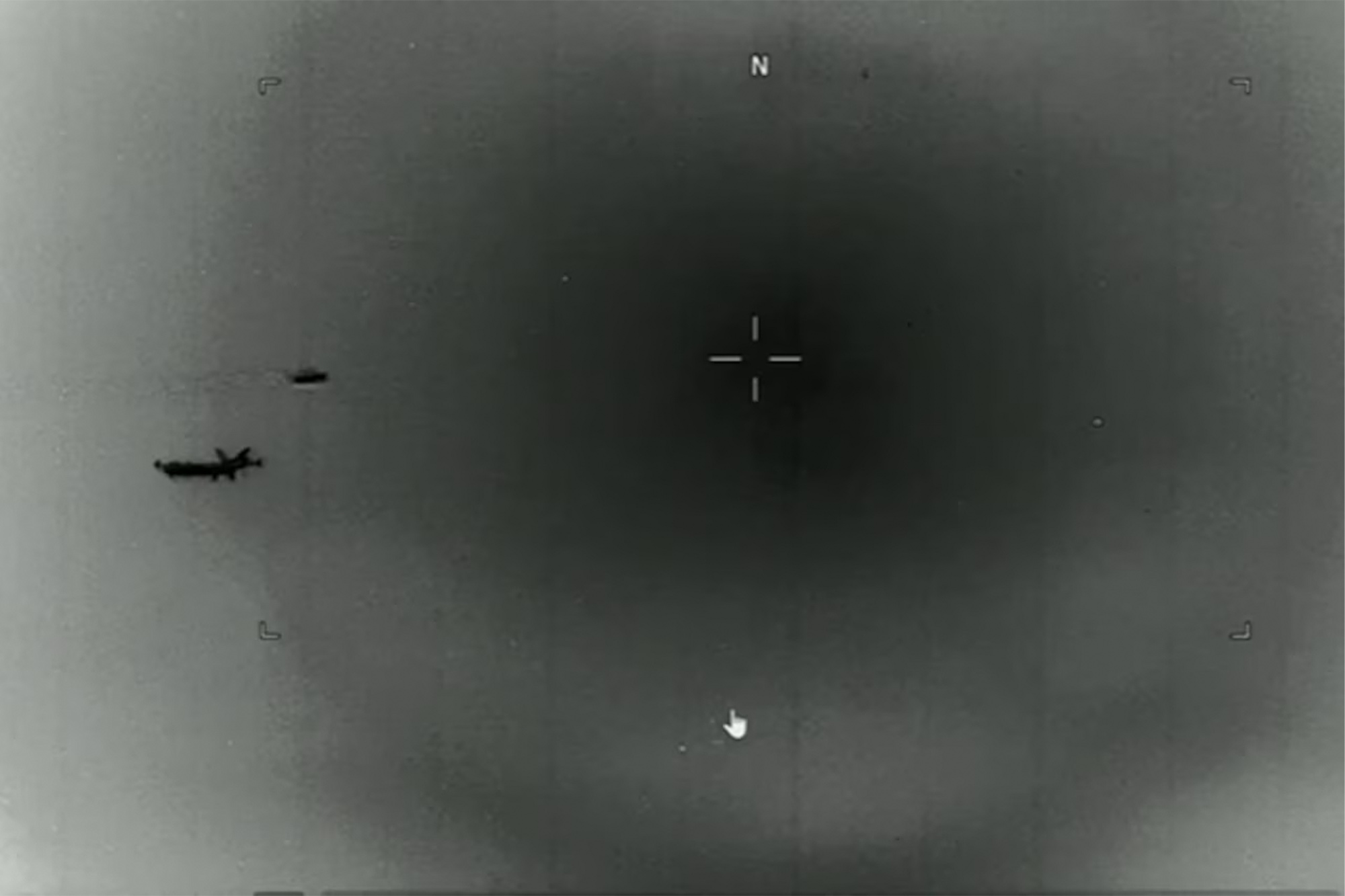

A declassified black-and-white image from the recent NASA hearing shows an example of an unidentified aerial phenomena. A video was being recorded of a drone in flight over the Middle East when an object, seen above the drone, passed by. The object remains unidentified. (U.S. Department of Defense photo)

Even though the United States government has acknowledged the existence of unidentified aerial phenomena - perhaps better known in popular culture as "unidentified flying objects," or UFOs - for many professors and researchers, the topic is still cringe-worthy.

So it's perhaps unexpected that almost a fifth of academics in a recent, anonymous survey said they've witnessed something in the skies they can't explain.

And it's perhaps a problem that they'd rather not discuss it openly.

Last week, an independent NASA panel reported that the lack of quality data on the phenomena, as well as negative public opinions about whether the research should be pursued, are the two biggest barriers to knowing more.

Bethany A. Bell, an associate professor in School of Education and Human Development at the University of Virginia, is one of the academics who is open to asking questions.

Bethany A. Bell, an associate professor in UVA's School of Education and Human Development, was eager to join the research team to help reduce the taboo of the subject area. (UVA School of Education and Human Development photo)

Bell joined primary authors Marissa E. Yingling and Charlton W. Yingling of the University of Louisville on their quest to know what scholars might be thinking about UFOs, but not willing to say out loud.

"My decision to join the team was mainly curiosity and interest in helping move a historically 'taboo' topic into intellectual spaces," said Bell, who chairs the Department of Education Leadership, Foundations and Policy.

In light of the NASA report, which now uses the government-preferred term "unidentified anomalous phenomena," the professors' May 23 publication of findings in the journal Humanities and Social Science Communications couldn't have been timelier.

The Survey and the Stigma

Hard to document, much less replicate for further study, the mysterious sightings often occur quickly, remotely and at night.

Those who choose to report an encounter do so at their own risk. Society has long been trained to respond with skepticism, if not outright hostility. Given the stigma, serious-minded people such as academics have learned to keep unexplainable encounters to themselves.

"Universities are institutions within the larger society - they are influenced by societal and cultural norms," Bell said. "It seems that historically, when the topic of UFOs began to appear, UFOs became synonymous with extraterrestrial beings - something that the majority of people consider in the same realm as Bigfoot or 'ghosts' and other paranormal phenomena."

In this green "night vision" photo, also released at the NASA hearing, a triangular or guitar-pick shaped object takes to the sky. The U.S. military can't account for it. (U.S. Navy photo)

But ever since the government added its imprimatur to investigate with last year's congressional hearings, the first on the topic in 50 years, the three university professors wanted to take the temperature of their fellow academics.

The team sent their survey to tenured and tenure-track faculty in 14 disciplines at 144 U.S. doctoral universities classified as conducting "very high research activity" by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education.

In addition to the types of academics one might expect, such as astronomers and physicists, the researchers wanted to hear from faculty in the social sciences, humanities and arts.

The team asked the academics how curious they were about the topic, how aware were they of related news developments and how interested they might be in conducting research, among other questions.

Even though the survey allowed for anonymity, the response rate was relatively small. Of the nearly 40,000 academics who received the email, only 1,549 returned answers.

Many of the professors apparently thought the survey was spam. After all, who asks about such things?

Some reacted unkindly. One wrote, "Tenure might be tricky for you - good luck."

Surprising Findings and Next Steps

In all of the instances in which the survey asked about awareness of news developments, most people said they were "not at all aware" - perhaps pointing to the taboo of discussion and sharing of the subject matter within their circles.

Curiosity was the biggest driver for those who said they had kept up with the news.

But what surprised the researchers most was the response to the question, "Have you or anyone close to you ever observed anything of unknown origin to you that might fit the U.S. government's definition of a UAP?"

About a fifth - 18.9% - said yes, while another 8.7% said maybe.

The researchers were also surprised by some of the responses to open-ended questioning.

The team didn't ask for specific experiences. Instead, they asked if there was anything else respondents wanted them to know.

One academic reported, "My entire family and I witnessed a UFO around 1976. It was over our house in the rural northeast (state redacted). Two of my siblings saw it, while the rest of us in the house felt it shake and heard a loud noise. We were eating dinner and the shaking was so intense that we all ran outside."

Another said, "I saw an unidentified flying object as a child in (state redacted) (with my sibling) - which my parents didn't believe. The news reported that others saw it, too."

A third respondent said they had witnessed two sightings.

"I used to tell people, but they thought I was crazy or lying - so now I'm silent."

Though the researchers didn't set out with an agenda, Bell said she was heartened by how respondents privately expressed the idea that learning more could have strong value.

When asked, "In your view, who stands to gain from the release of UAP-related information? Please select all that apply," about 54% responded "all humanity."

"Given that faculty in our sample think academic evaluation of UAP and related research are important, we hope that this study adds credibility to discussing the topic openly," Bell said. "Without engaging in a conversation about what is occurring in our federal government, how can faculty begin to evaluate information related to this topic?"

She said the next step is for academics from numerous disciplines to be "at the table."

To her mind, whether UAP exist is no longer the question. The question is: What are they?