Corals are among the most fascinating and essential living organisms on our planet. These complex creatures are the architects of the sea, constructing vibrant underwater cities that support a quarter of all marine life. Corals are also vulnerable. As climate change intensifies, rising ocean temperatures, mass coral bleaching events and habitat loss are putting their future at risk.

Research into coral biology has accelerated in recent years, driven by the urgent need to protect these irreplaceable ecosystems. Studying corals is not an easy task—many species only reproduce once a year, they grow slowly and they live in complex and remote marine environments. Through perseverance and innovation, researchers continue to uncover critical information, providing insights into how corals live, reproduce and adapt.

Here are 5 recent and surprising discoveries about corals that offer hope for protection efforts and a better future for reefs:

#There's more coral biodiversity than we thought

Research from the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP) has revealed that an unexpectedly large proportion of coral species are harbouring a genetic secret.

Each species of coral might look visually unique to the human eye, but at a genetic level, the difference between one species and another is not as clear-cut. This means that corals of one species can crossbreed with another to form new 'cryptic' groups.

Now, through review and research led by The University of Queensland and the Australian Institute of Marine Science, we know that the extent of these hidden coral groups on our Great Barrier Reef is as high as 68%.

Awareness of these hidden reproductive groups is incredibly important for restoration efforts, that aim to breed and plant new corals onto the Reef. By knowing the genetic limits, or possibilities, and importantly, where they occur on the Reef, we can more carefully select and outplant corals for restoration.

Researchers continue to uncover critical insights into how corals live, reproduce and adapt. Credit: Marie Roman, Australian Institute of Marine Science.

#Corals have a huge range of heat tolerance

Scientists have found a huge variety of heat tolerance within corals from across the length and breadth of the Great Barrier Reef.

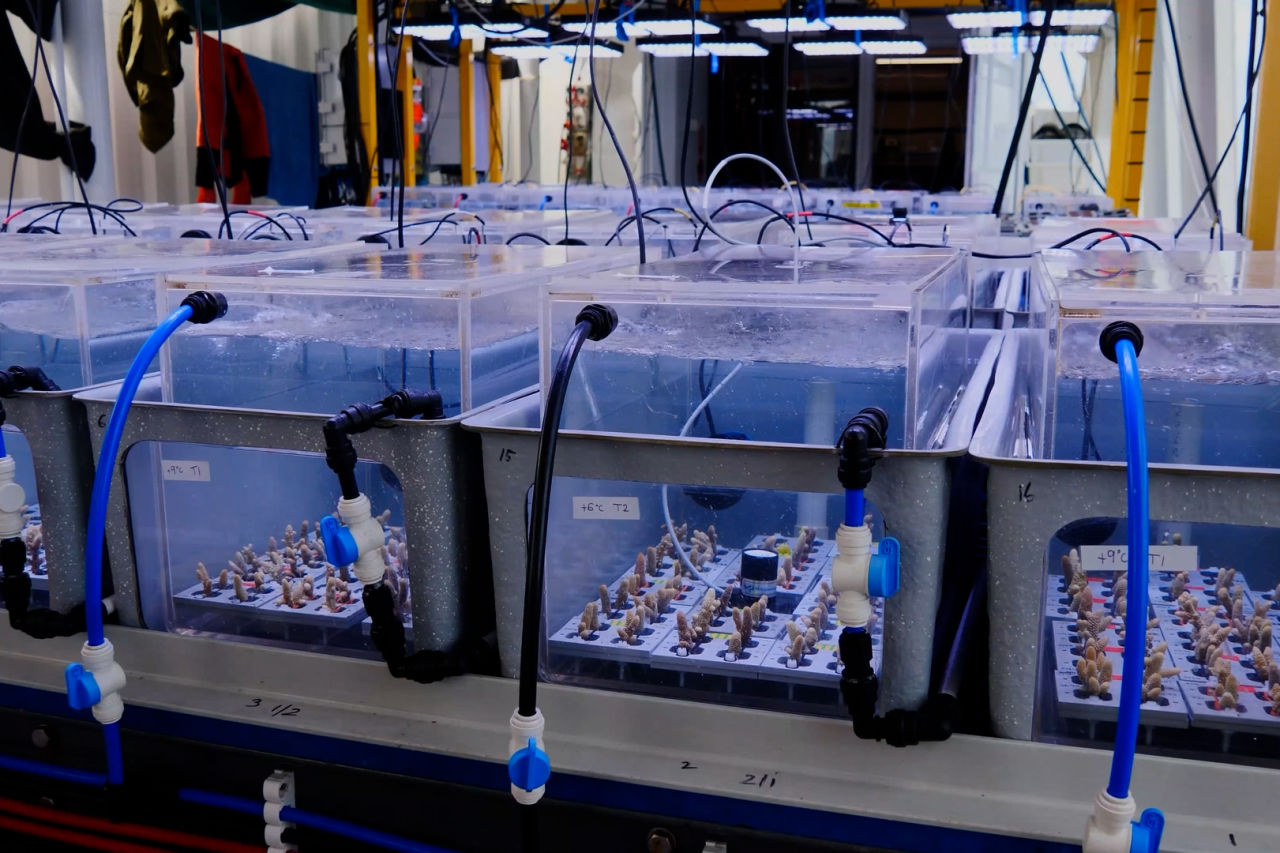

RRAP researchers from Southern Cross University and the Australian Institute of Marine Science found that corals of the same species can have vastly different heat tolerance, even when growing side by side. The tolerance threshold differed by up to 8 degrees in some locations. This variation is driven by genetics, environmental factors, and symbiotic algae.

The discovery offers a potential lifeline for reefs facing increasing heat stress. Identifying this natural adaptation provides valuable insights for reef conservation, including selective breeding and restoration programs aimed at improving reef resilience.

The heat tolerance threshold of corals can vary up to 8 degrees in some locations. Credit: Australian Institute of Marine Science.

#Corals need to be closer than expected to reproduce

A study into coral reproduction has discovered the closer the better, according to co-funded RRAP research led by The University of Queensland and CSIRO.

Corals increase their reproductive success by simultaneously releasing millions of egg-sperm bundles during mass spawning events, improving the chances these bundles will find a matching species and fertilise.

Researchers measured fertilisation success during spawning and discovered that corals in Palau need to be within 10 meters of each other for effective reproduction, ideally even closer. At 10 meters, fertilisation rates dropped below 10% and became nearly zero at 20 meters. Coral bleaching events are rapidly decreasing coral density, making reproduction more difficult. Understanding this data can help guide coral restoration and coral planting efforts.

Coral spawning events are key to scaling up and accelerating restoration. Credit: Gary Cranitch.

#Corals chemically find their forever home

When reproductive bundles fertilise into larvae during spawning, they don't just drift and settle anywhere. These free-swimming baby corals use natural chemical signals from the reef to find the perfect place to settle. Discovering more about this process could help us to better restore coral reefs.

RRAP researchers have been deep-diving into the particular cues for Great Barrier Reef coral species, uncovering the exact chemical cues and bacteria that guide and encourage these particular baby corals to safe and ideal settlement sites. If the right signals aren't present, larvae will keep searching or delay settling. This behavioural insight can help researchers create better conditions for growing corals for restoration and thereby improving the chances of new coral growth in damaged reef areas. Adding to these settlement cues, researchers have also been designing cradle-like devices that can improve baby corals' odds of survival and safely house newly settled corals after they've been planted on the Reef.

A free swimming larvae settles on a suitable rock surface. Credit: Peter Harrison.

#Some coral species can walk

While most corals stay anchored in their forever home, some species, like mushroom corals, can relocate themselves. Using time-lapse cameras, researchers at the Queensland University of Technology have observed corals shifting slowly across the seafloor.

They move by inflating and deflating their bodies, similar to how jellyfish can pulse through the water. This movement is slow - only a few inches per day - but significant for their size.

This discovery challenges the idea that corals are stationary and suggests that coral mobility is a built-in survival strategy that could help mushroom corals as our climate changes. Instead of staying in one spot, they migrate to settle in deeper, cooler and calmer waters as they grow. This reduces competition, increases population density for reproduction and can better insulate them from sea surface temperature changes.

Top image: Research is providing insights into coral that could help us better protect them. Credit: Australian Institute of Marine Science.

The Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program aims to reduce critical uncertainty around a suite of possible interventions, to help develop a safe, cost-effective, and acceptable toolkit for restoration and adaptation. Program Partners include: the Australian Institute of Marine Science, the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, CSIRO, The University of Queensland, Queensland University of Technology, Southern Cross University and James Cook University.