"You shouldn't try to make yourself into something you're not."

That was the advice William Paris was given by his academic supervisor in graduate school. At the time, he was studying European philosophers - but finding his interest waning.

"I began realizing these figures couldn't answer the questions I was interested in," says Paris, a new assistant professor in the University of Toronto's department of philosophy in the Faculty of Arts & Science.

"I was asking questions like, 'What is the relationship between slavery and modern politics now? How is it that racism continues to be a problem, even though it has been thoroughly delegitimated ideologically and scientifically?' It felt like I was trying to push a square peg into a round hole."

Following his supervisor's words - and his own passions - Paris became a scholar of Africana philosophy, exploring thinkers from Africa as well as philosophers of the African diaspora who settled in the Caribbean, North America and around the world.

"Africana philosophy asks questions around, 'How does racism reproduce itself? What does national belonging mean?' It tries to understand the relationship between race, colonialism and empire."

Who are some of these philosophers?

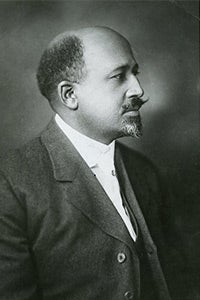

W.E.B. Du Bois

There are several, but Paris wishes more people knew about W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) and Frantz Fanon (1925-1961).

An American sociologist, historian, author and activist, Du Bois is regarded as the most important Black protest leader in the United States during the first half of the 20th century. He was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

"Du Bois is essential for asking the questions like 'what does it mean to say that a society has racial problems or that society is structurally racist?'" says Paris.

Considered ahead of his time, Du Bois was an early champion of using social science data to solve social issues for the Black community. His writing, including The Souls of Black Folk, became required reading in African American studies.

"He's not just a great lyricist," says Paris. "He's an incredible philosopher who gives insight into what it means to try to figure out a relationship between philosophy and social science that can lead us to more liberatory forms of life."

Fanon, meanwhile, was a psychiatrist and political philosopher from Martinique who was concerned with the psychosocial repercussions of colonialism on colonized people. His major contributions to de-colonial thinking stemmed from his experiences working at the Blida-Joinville Hospital in Algeria during the Algerian War of Independence (1954-1962).

He later created a model for community psychology, believing that many mental health patients would fare better if they were integrated into their families and communities, rather than being treated in institutionalized care settings.

"For him, it was never about blaming people for their unhealthy behaviors," says Paris. "It was about reconstructing a society that embraces the human creatures we are so that we can have healthy relationships with one another.

"I'm drawn to these Africana thinkers who are also interested in scientific study," adds Paris. "They weren't just talking about their lived experience. They wanted to develop objective methods that can allow us to grasp what the problem is - and then transform it."

Du Bois and Fanon are sometimes referenced in his course, "Philosophy and Social Criticism," which focuses on how our notions of justice change over time.

"We've finished the first unit which is about critiquing the present - what does it mean to understand the time you're living in?" says Paris.

Frantz Fanon

The course includes discussions of contemporary philosophers such as Martin Hägglund and his book This Life, in which he argues that spiritual questions of freedom are inseparable from economic and material conditions, and that what matters is how we treat one another in this life and what we do with our time.

"Then we read Theodor Adorno and his essay called 'Free Time,' where he argues that the very fact that we have to call our time 'free' means that it's not actually very free."

The course also addresses philosophy as it relates to climate change and the role of politics.

"Often our democracy focuses on how we meet the needs of the existing population, but we're increasingly talking about what world are we handing down to our grandchildren who are not here yet." says Paris.

In addition to teaching, Paris and some academic colleagues host a monthly podcast called "What's Left for Philosophy" that's described as, "Four Marxist friends discussing philosophy, politics, and culture."

"We're trying to make philosophy accessible to those who don't study philosophy - or even to those who do - in an effort to rediscover the joy of thinking," says Paris.

With rotating hosts and guests, there's no competition to see who knows or understands more. Instead, it's a relaxed atmosphere where the ideas, theories and discussion flow freely.

"We're just here to think together," says Paris. "It's actually a way for me to decompress."

Paris is also working on a book called Racial Justice and Forms of Life: Towards a Critical Theory of Utopian Epistemology.

The book begins with the question: Why is it so hard to complete the project of racial justice in countries, primarily in the West?

"The manner in which we arrange our lives makes it so that racial hierarchy and domination are almost inevitable consequences, so we shouldn't be surprised our efforts in modifying problems of racial justice keep being stymied," says Paris.

"I'm arguing that we need to develop new habits and new modes of knowing that can allow us to understand how we can develop a new form of life. It's important for us to get beyond the pessimism of, 'All we can do is modify the status quo and accept disappointment,' and ask the real question of what it would mean to move past disappointment and actually complete a project of freedom."