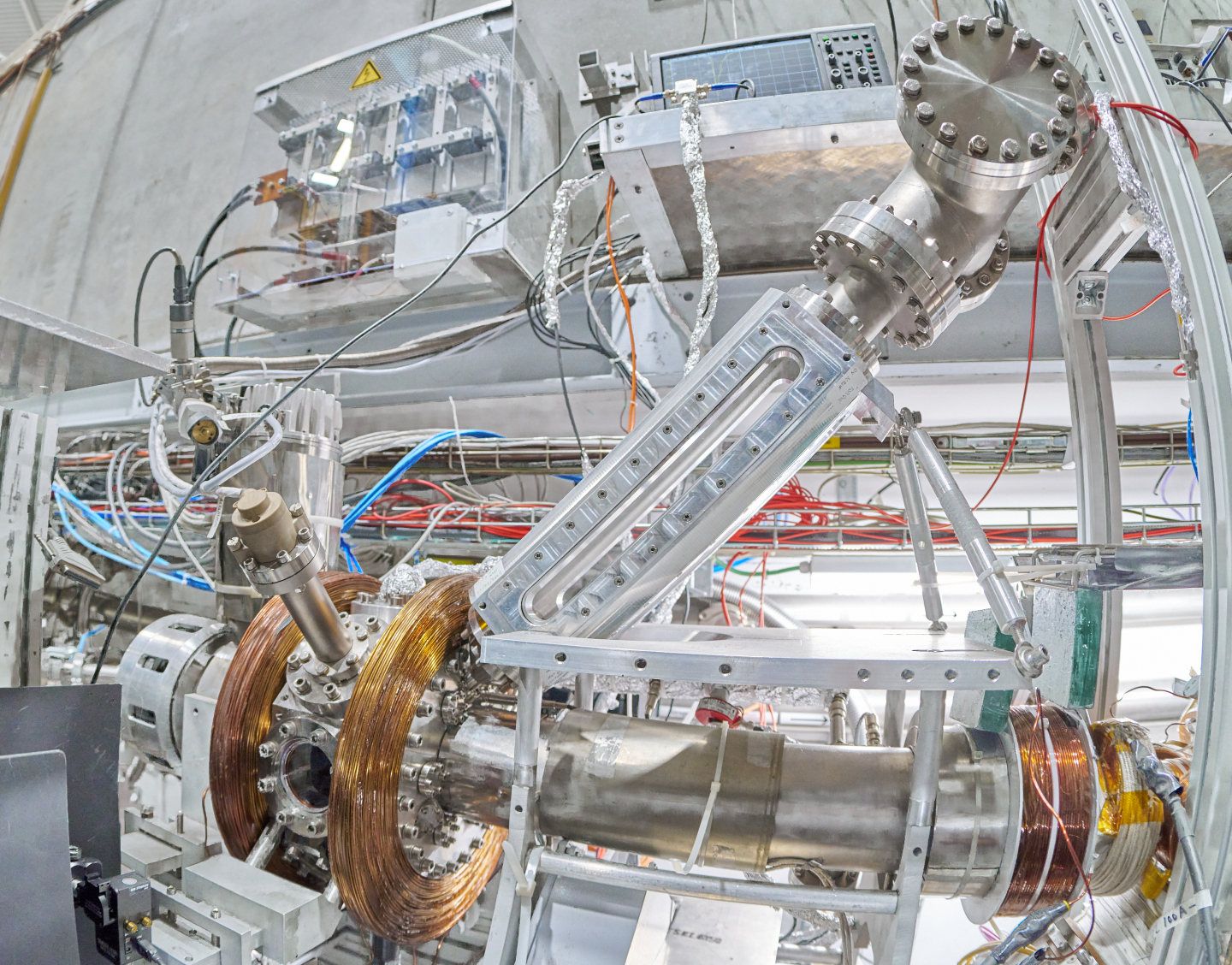

The set-up used by the AEgIS team to laser-cool positronium. (Image: CERN)

AEgIS is one of several experiments at CERN's Antimatter Factory producing and studying antihydrogen atoms with the goal of testing with high precision whether antimatter and matter fall to Earth in the same way. In a paper published today in Physical Review Letters, the AEgIS collaboration reports an experimental feat that will not only help it achieve this goal but also pave the way for a whole new set of antimatter studies, including the prospect to produce a gamma-ray laser that would allow researchers to look inside the atomic nucleus and have applications beyond physics.

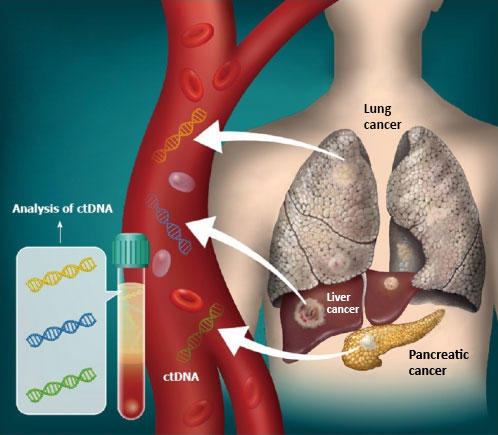

To create antihydrogen (a positron orbiting an antiproton), AEgIS directs a beam of positronium (an electron orbiting a positron) into a cloud of antiprotons produced and slowed down in the Antimatter Factory. When an antiproton and a positronium meet in the antiproton cloud, the positronium gives up its positron to the antiproton, forming antihydrogen.

Producing antihydrogen in this way means that AEgIS can also study positronium, an antimatter system in its own right that is being investigated by experiments worldwide.

Positronium has a very short lifetime, annihilating into gamma rays in 142 billionths of a second. However, because it comprises just two point-like particles, the electron and its antimatter counterpart, "it's a perfect system to do experiments with", says AEgIS spokesperson Ruggero Caravita, "provided that, among other experimental challenges, a sample of positronium can be cooled enough to measure it with high precision".

This is the feat accomplished by the AEgIS team. By applying the technique of laser cooling to a sample of positronium, the collaboration has already managed to more than halve the temperature of the sample, from 380 to 170 degrees kelvin. In follow-up experiments the team aims to break the barrier of 10 degrees kelvin.

AEgIS' laser cooling of positronium opens up new possibilities for antimatter research. These include high-precision measurements of the properties and gravitational behaviour of this exotic but simple matter-antimatter system, which could reveal new physics. It also allows the production of a positronium Bose-Einstein condensate, in which all constituents occupy the same quantum state. Such a condensate has been proposed as a candidate to produce coherent gamma-ray light via the matter-antimatter annihilation of its constituents - laser-like light made up of monochromatic waves that have a constant phase difference between them.

"A Bose-Einstein condensate of antimatter would be an incredible tool for both fundamental and applied research, especially if it allowed the production of coherent gamma-ray light with which researchers could peer into the atomic nucleus." says Caravita.

Laser cooling, which was applied to antimatter atoms for the first time about three years ago, works by slowing down atoms bit by bit with laser photons over the course of many cycles of photon absorption and emission. This is normally done using a narrowband laser, which emits light with a small frequency range. By contrast, the AEgIS team uses a broadband laser in their study.

"A broadband laser cools not just a small but a large fraction of the positronium sample," explains Caravita. "What's more, we carried out the experiment without applying any external electric or magnetic field, simplifying the experimental set-up and extending the positronium lifetime."

The AEgIS collaboration shares its achievement of positronium laser cooling with an independent team, which used a different technique and posted their result on the arXiv preprint server on the same day as AEgIS.

Further material:

About AEgIS:

The AEgIS collaboration is composed of several research groups from CERN, Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (units of Milano, Pavia and the Trento Institute for Fundamental Physics and Applications), the University of Oslo, the Universite Paris-Saclay and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the University of Liverpool, the Warsaw University of Technology, the University of Trento, the Jagiellonian University of Krakow, the Raman Research Institute of Bangalore, the University of Innsbruck, the University and the Politecnico of Milan, the University of Brescia, the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, the University of Latvia, the Institute of Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences and the Czech Technical University of Prague.