Was the pandemic a moment of cultural divide, or were Brits "all in it together"?

The National Institute for Health and Care's Emergency, Preparedness and Response Health Protection Research Unit (EPR HPRU) is a partnership between King's College London, Public Health England and the University of East Anglia.

This piece is taken from an essay collection showcasing the unit's critical role in the UK's response to Covid-19.

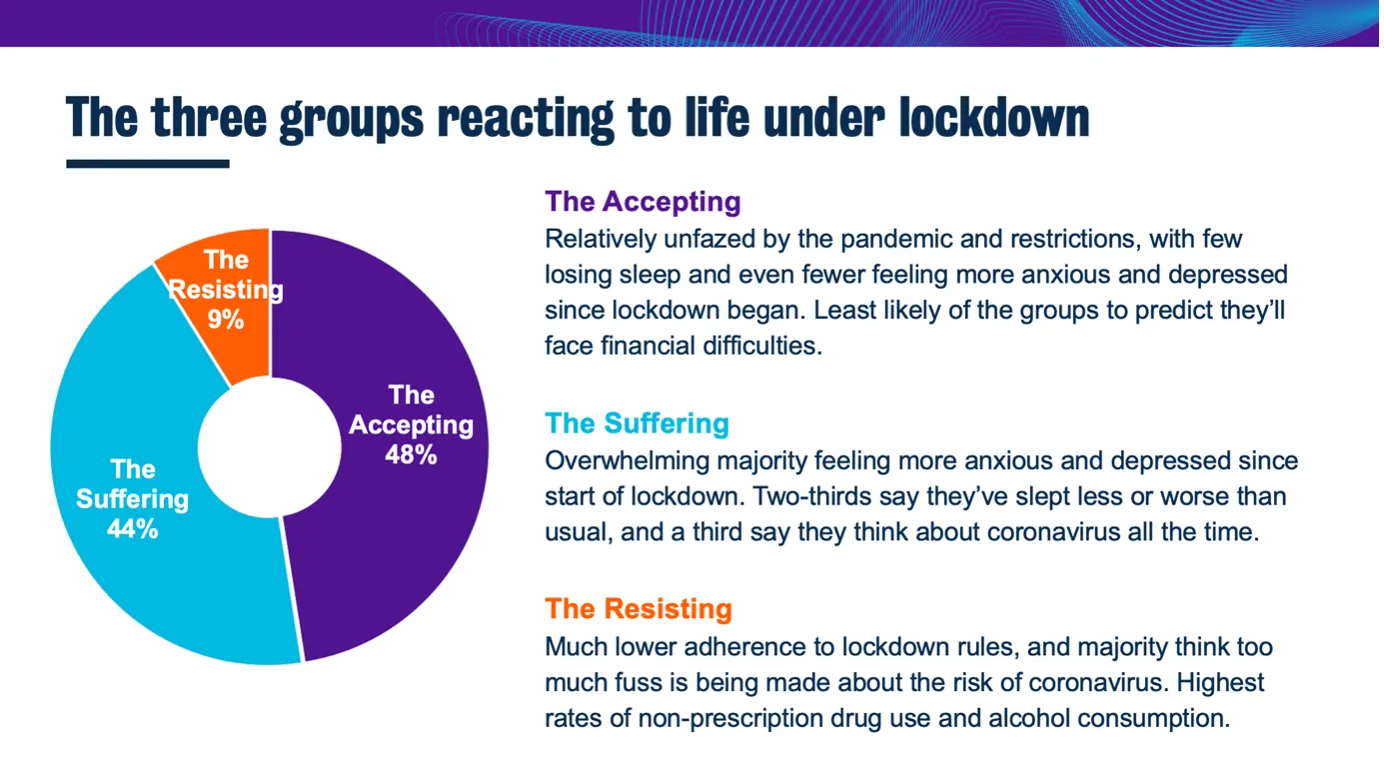

At the beginning of the pandemic, in April 2020, we identified three main clusters within the population: the "Accepting", the "Suffering" and the "Resisting". You can get an idea of their very different experiences of Covid-19 through their responses to just a few questions (see Figure 1).

For example, when asked about their experiences of lockdown, nearly all of the "Suffering" group said they were more anxious or depressed since the measures were announced, compared with just eight per cent of the "Accepting". And a third of the "Suffering" said they thought about coronavirus all the time.

The "Accepting", on the other hand, were much less likely to have experienced some of the key negative impacts identified in the survey. Only 12 per cent said they had slept less or less well than before the lockdown, compared with an incredible 64 per cent of the Suffering.

These two groups made up most of the population, compared with the "Resisting", who represented nine per cent of UK adults. This group – still around five million people – were particularly likely to have argued with their family or housemates and had both drank more alcohol than they normally would or used non-prescription drugs.

Three in five of the "Resisting" also thought that "too much fuss" was being made about the risk of coronavirus, and a third expected life to return to normal within two months – much higher than the other groups.

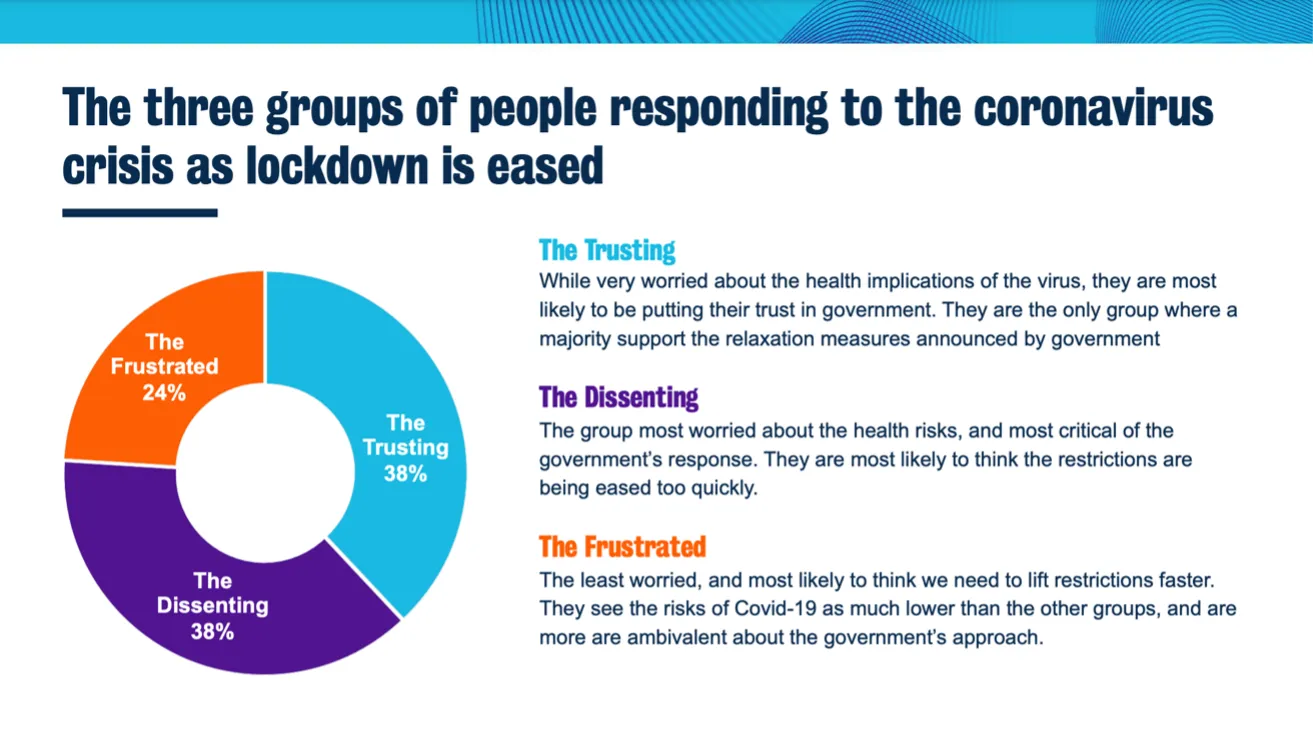

As the months went by and this prediction proved wide of the mark, tensions grew about the UK's route out of the crisis, and the focus shifted to how the government was managing the easing of the restrictions (see Figure 2).

Where once the country had been united on the decision to go into lockdown, this consensus fractured as we emerged, with the public's views starting to line up more with their underlying political identities.

Hence our analysis found the "Trusting" – who, despite their concerns about the virus, had the most faith in the government's plan to relax the measures – were overwhelmingly Conservative voters, while the "Dissenting" – who were most critical of the government's response and thought the measures were being eased too quickly – were largely Labour voters.

A third, smaller group – the "Frustrated" – were more evenly balanced in terms of political support and felt the restrictions were being relaxed too slowly, in part because they were more likely to be suffering from the economic impacts of the lockdown.

The crisis seemed set to become another element of our often-divisive politics and our nascent "culture war", where politics reach into more aspects of our lives, and where our views become increasingly set by which political "tribe" we're in.

In practice, our Covid-19 attitudes did not turn out to be quite the cultural divide that many expected – because they did not align well with other key cultural divides, such as our attitudes to Brexit.

The most prominent lockdown-sceptic voices – from Julia Hartley-Brewer, Allison Pearson and Toby Young, to Steve Baker, Daniel Hannan and Nigel Farage – also shared a distrust of the European Union. Nigel Farage even launched a new political party, Reform UK, whose initial focus was promoting lockdown scepticism. But our analysis of lockdown and Brexit divides among the broader public showed there was a very poor values fit between lockdown scepticism and Brexit support.

Those who prioritised civil liberties over combatting the virus – lockdown sceptics – disproportionately prioritise what the values model calls "hedonism", "stimulation", "power" and "achievement". By contrast, those who were more accepting of limits on freedoms during the pandemic overwhelmingly valued "security", "conformity", "universalism" and "benevolence".

These different sets of values do not fit at all well with the values divide that characterised Brexit. In the case of the EU referendum vote, people who valued universalism were the strongest supporters of Remain, and those valuing security and tradition were the strongest backers of Leave. But these two value sets and groups found themselves somewhat united in support of lockdowns – and lockdown scepticism remained a relatively niche front in our supposed "culture wars" (see Figure 3).

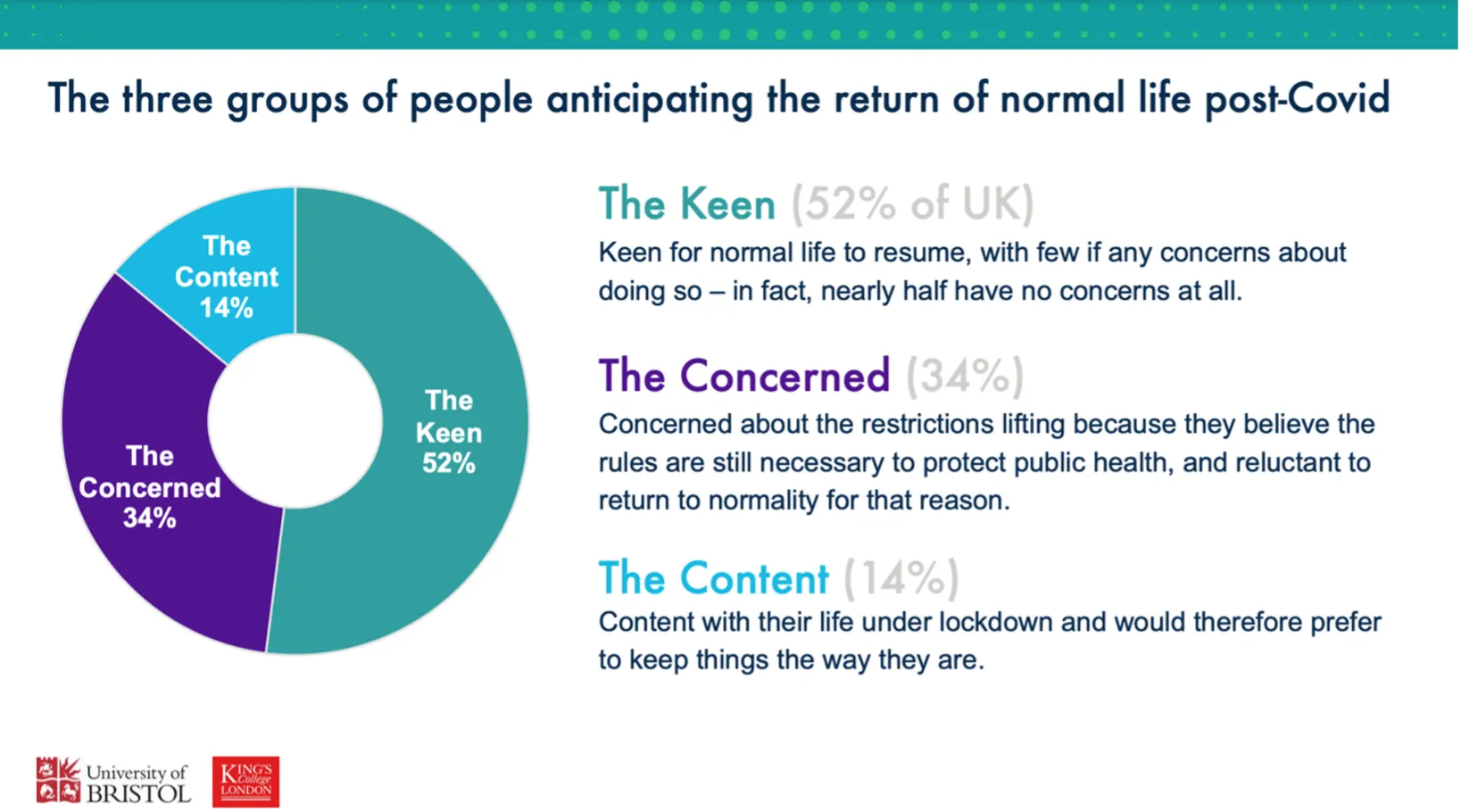

Our attitudes continued to shift, as a return to normal life seemed more realistic. After a winter lockdown, the success of the vaccine rollout meant that a clearer path out of the UK's pandemic was now visible, and by May 2021 the key question was whether the public were keen to get back to normal life, concerned about society opening up too quickly, or pretty content with locked-down living.

The "Keen" were the largest group we identified, making up one half of the population, while the other half split into two groups with very different reasons for being more reticent. The bigger group – the "Concerned", who represent around a third of the public – remained worried about catching Covid-19, the emergence of new strains, and whether we'd vaccinated enough people to justify opening up.

But there are also one in seven people – the "Content" – who said they were quite enjoying aspects of our new way of living. They were saving money, liked working from home, and were just happy meeting fewer people than they used to.

In it together or deeply divided?

Throughout all the shocks and turbulence of the past two years, with their drastically different impacts on different sections of the population, there was an important constant – the extraordinarily high level of compliance with Covid-19 restrictions.

Even though many were struggling, the overwhelming majority of people continued to follow the rules, even if they themselves were at a relatively lower risk from the virus. But not everyone got the recognition they deserved.

Young people, by and large, adhered to the restrictions as much as everyone else. And despite sacrificing formative life experiences and seeing their education and careers suffer, they were still more likely to be seen as selfish rather than selfless in how they behaved during the pandemic.

Such resentment was thankfully hard to detect among our collective national effort – but it did exist. In July 2020, half the population said they felt angry with people they know because of how they'd behaved during the crisis. A quarter said they'd had arguments as a result, and one in 12 said they were no longer speaking to someone because of pandemic disagreements.

Over a year later, as a more permanent end to the UK's crisis looked more likely, there were still signs of discontent. In November/December 2021, around one in 10 people said they would potentially support violent protests if the UK government either refused to impose a lockdown when doctors and scientists advised it was needed or if it imposed a lockdown they didn't agree with.

That may sound shocking, but we could have perhaps expected worse given the extent of the upheaval the country has endured. We fared pretty well when you consider that, according to our findings, more people would support violent demonstrations in response to a war – or even a tax increase – they didn't agree with.

It's undoubtedly the case that small segments of the population have been pushed towards extreme views through their experience of the pandemic – in either seeing restrictions as an outrageous attack on civil liberties, or believing the government and society betrayed or abandoned them through careless actions or bad strategy. Throughout the pandemic, our studies showed the key role that our fractious social media environment played in splintering off small sections of the public.

But in the end, despite the extraordinary measures the pandemic required, we seem to have avoided the worst of Covid-19 attitudes aligning with, and giving new impetus to, other deep divides and political identities. We may not have been completely in it together, but we could have come out of it a lot worse.

Bobby Duffy is a Professor of Public Policy and Director of the Policy Institute at King's College London