Discovery by international team, including Rutgers researcher, proves theory that some ancient hominins were neighbors

More than a million years ago, on a hot savannah teeming with wildlife near the shore of what would someday become Lake Turkana in Kenya, two completely different species of hominins may have passed each other as they scavenged for food.

Scientists know this because they have examined 1.5-million-year-old fossils they unearthed and have concluded they represent the first example of two sets of hominin footprints made about the same time on an ancient lake shore. The discovery will provide more insight into human evolution and how species cooperated and competed with one another, the scientists said.

"Hominin" is a newer term that describes a subdivision of the larger category known as hominids. Hominins includes all organisms, extinct and alive, considered to be within the human lineage that emerged after the split from the ancestors of the great apes. This is believed to have occurred about 6 million to 7 million years ago.

The discovery, published today in Science, offers hard proof that different hominin species lived contemporaneously in time and space, overlapping as they evaded predators and weathered the challenges of safely securing food in the ancient African landscape. Hominins belonging to the species Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei, the two most common living human species of the Pleistocene Epoch, made the tracks, the researchers said.

"Their presence on the same surface, made closely together in time, places the two species at the lake margin, using the same habitat," said Craig Feibel, an author of the study and a professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences and Department of Anthropology in the Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences.

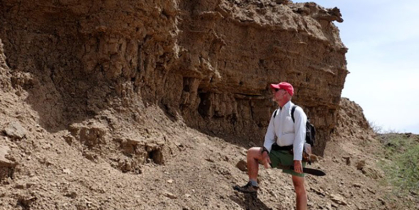

Feibel, who has conducted research since 1981 in that area of northern Kenya, a rich fossil site, applied his expertise in stratigraphy and dating to demonstrate the geological antiquity of the fossils at 1.5 million years ago. He also interpreted the depositional setting of the footprint surface, narrowing down the passage of the track makers to a few hours, and showing they were formed at the very spot of soft sediments where they were found.

If the hominins didn't cross paths, they traversed the shore within hours of each other, Feibel said.

While skeletal fossils have long provided the primary evidence for studying human evolution, new data from fossil footprints are revealing fascinating details about the evolution of human anatomy and locomotion, and giving further clues about ancient human behaviors and environments, according to Kevin Hatala, the study's first author, and an associate professor of biology at Chatham University in Pittsburgh, Pa.

"Fossil footprints are exciting because they provide vivid snapshots that bring our fossil relatives to life," said Hatala, who has been investigating hominin footprints since 2012. "With these kinds of data, we can see how living individuals, millions of years ago, were moving around their environments and potentially interacting with each other, or even with other animals. That's something that we can't really get from bones or stone tools."

Hatala, an expert in foot anatomy, found the species' footprints reflected different patterns of anatomy and locomotion. He and several co-authors distinguished one set of footprints from another using new methods they recently developed to enable them to conduct a 3D analysis.

"In biological anthropology, we're always interested in finding new ways to extract behavior from the fossil record, and this is a great example," said Rebecca Ferrell, a program director at the National Science Foundation who helped fund this portion of the research. "The team used cutting-edge 3D imaging technologies to create an entirely new way to look at footprints, which helps us understand human evolution and the roles of cooperation and competition in shaping our evolutionary journey."

Feibel described the discovery as "a bit of serendipity." The researchers uncovered the fossil footprints in 2021 when a team organized by Louise Leakey, a third-generation paleontologist who is the granddaughter of Louis Leakey and daughter of Richard Leakey, discovered fossil bones at the site.

The field team, led by Cyprian Nyete, mainly consists of a group of highly trained Kenyans who live locally and scour the landscape after heavy rains. They noticed fossils on the surface and were excavating to try and find the source. While cleaning the top layer of a bed, Richard Loki, one of the excavators, noticed some giant bird tracks, then spotted the first hominin footprint. Leakey coordinated a team in response that excavated the footprint surface in July 2022.

Feibel noted it has long been hypothesized that these fossil human species coexisted. According to fossil records, Homo erectus, a direct ancestor of humans, persisted for 1 million years more. Paranthropus boisei, however, went extinct within the next few hundred thousand years. Scientists don't know why.

Both species possessed upright postures, bipedalism and were highly agile. Little is yet known about how these coexisting species interacted, both culturally and reproductively.

The footprints are significant, Feibel said, because they fall into the category of "trace fossils" - which can include footprints, nests and burrows. Trace fossils are not part of an organism but offer evidence of behavior. Body fossils, such as bones and teeth, are evidence of past life, but are easily moved by water or a predator.

Trace fossils cannot be moved, Feibel said.

"This proves beyond any question that not only one, but two different hominins were walking on the same surface, literally within hours of each other," Feibel said. "The idea that they lived contemporaneously may not be a surprise. But this is the first time demonstrating it. I think that's really huge."