The letters of a British woman who toured Australia and New Zealand raising funds for a southern solar observatory are among the latest pieces of Australia's science history to be shared from the Academy's archives.

Canberra's Shine Dome is home to the Australian Academy of Science Basser Library and Fenner Archives collections, which together significantly contribute to documenting the history of science in Australia.

The Fenner Archives contain primary documents from the lives of many of the Academy's eminent fellows. These field books, letters, photographs, draft works and sketches are accessible to researchers by appointment.

One researcher who visited the archives earlier this year was Curator of Social History, Dr Hannah Paddon from the Canberra Museum and Gallery (CMAG), who accessed and viewed documents from the Walter Duffield collection (MS095) which date from the early 1900s.

Her research visit was in preparation for the exhibition Outer Space: Stromlo to the Stars, commemorating Mount Stromlo's 100th anniversary-a project made more challenging due to record losses during the three bushfires Mount Stromlo had suffered in the last century.

The Duffield collection at the Academy captures the persistent and world-wide campaign, spear-headed by Dr Duffield, to see a solar observatory established in Canberra.

Dr Paddon's visit and subsequent loan request to have physical documents from the archives be part of the upcoming exhibition resulted in further research and digitising of the collection.

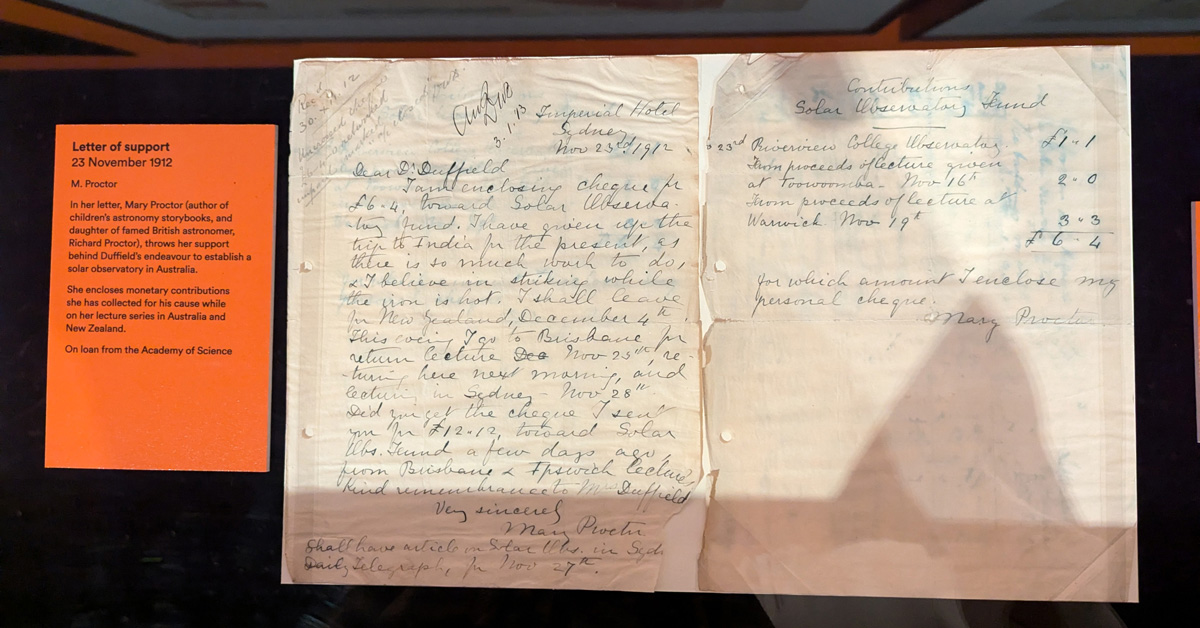

In the exhibition, a total of 10 documents from the Fenner Archives are now on public display for the first time.

The exhibition opened earlier this month and will run until 16 November 2025.

The collection

Dr Walter Duffield was the first director at the Mount Stromlo Observatory. His collection at the Academy provides a clear picture of the amount of international support there was for the building of the observatory and the sustained petitioning that happened over 15 years.

His scrapbook, also housed at in the Fenner Archives, was made available online through Trove this year thanks to the Community Heritage Grant from the National Library of Australia.

The book chronicles how his advocacy for an observatory started early as a recent graduate in 1907 and continued until his death in 1929.[1]

He argued, as did the international scientific community, that there needed to be a solar telescope in the South Pacific to fill a gap in solar observations globally.[2]

The wonderful result of researchers visiting our archives is that treasures can be revealed and further highlighted. It was among Dr Duffield's wider papers that Dr Paddon found another example of his international collaboration.

Among bequest and fundraising letters, Dr Paddon highlighted the importance of one author: Mary Proctor.

Proctor was an English science promoter, something a modern audience would now regard as a professional science communicator.

She toured Australia and New Zealand at the invitation of Dr Duffield from 1912 to 1914, promoting the need for an observatory and fundraising on their behalf.

The Fenner Archives hold her 1912 letter to Dr Duffield.

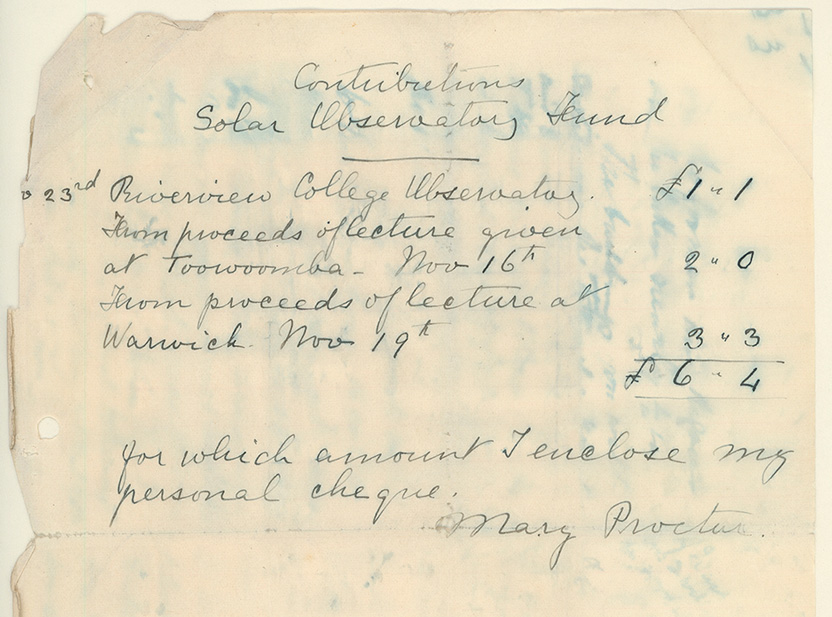

The two pages consist of a hastily written note and accounting of funds. It records her forwarding £6''4 for the Solar Observatory fund.

The letter was sent while on the Australian leg of her lecture tour, and the second page of her letter clarifies that the money Proctor is sending is coming from proceeds of her lecture series in Toowoomba on 16 November, and from proceeds three days later, from a lecture in Warwick.

It also notes £1''1 came from the small Riverview College Observatory in NSW which had been open for only four years.[3]

While six pounds does not sound too impressive to us today, the UK's National Archives currency converter indicates that £6''4 roughly converts to £484.67 in 2017[a], which roughly equates to A$949 today.

Using the same estimations, Proctor's earlier amount of 12 pounds would be in the ballpark of $1,928.00 today.

An important early science author, journalist and speaker, Proctor's visit to Australia and New Zealand was well covered in the newspapers at the time.[4]

Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne Martin Bush estimates that her tour possibly contributed a total close to £200 by the end of 1913 and believes that although not the largest financial contributor to the Solar Observatory project, her tour happened at an integral point for the Australian public.[5]

Her 1912 letter is special as it provides firm figures raised at two of her Australian lectures and shows her scientific lectures were well received by Australian audiences.

The letter is also a testament to difficulties of international fundraising in the 20th century with an annotation on the top left reading 'Rec.d 30.xii.12 Uncrossed cheque £6-4-0 returned unpaid, marked 'a/c closed', followed by possibly the words 'Acc Due 3.1.13' and may provide further weight to why Proctor was checking if her prior cheque had been received yet.

Despite the fund transfer difficulties for Dr Duffield, the letter does provide an early Australian example of how 'science celebrities' were used to promote a cause and fundraise in the 20th century, even rarer as the lecturer was a woman.

Readying items for participation in an exhibition

Proctor's hastily written letter is also one of five initial items loaned to CMAG for display, making this exhibition a special occasion where Mary Proctor's handwriting can be seen in person on public display.

As well as highlighting the important authors, the loan of material has also provided greater documentation of the condition of specific documents as they underwent a review for inclusion in a condition report before leaving the Shine Dome.

This process documents and records the position and degree of any damage or deterioration of each document and reveals Mary Proctor's letter is in relatively fair condition for being over one hundred years old!

It also provided insight into how the document was handled and stored. The inspection revealed that at some stage the letter's thin pages were pinned together.

Much of Dr Duffield's collection appears to have at one time been exposed to water with ink, mostly a highly dissolvable purple ink, having migrated to many neighboring documents.

It remains unclear what happened to the collection, but considering many family heritage documents are destroyed in leaks and floods, the Academy and the wider community is very fortunate to still have access to this document and the collection.

Mary Proctor's letter and Dr Duffield's wider collection are a testament to the importance of ongoing researcher engagement and the treasures still hiding in the archival boxes of the Fenner Archives.

The loan of material also ensured documents that had not yet been digitised were scanned in-house to a high standard with equipment made possible through the generous support of Academy supporter Professor David Anstice. Four Mount Stromlo Manuscript booklets, which are also part of the exhibition, would have proven challenging to scan without this equipment.

Support our work

If you would like to support the preservation of Australia's scientific legacy and help us to bring more of our collections and conversations online, for everyone please donate or contact us at [email protected]