It is widely believed that Earth's atmosphere has been rich in oxygen for about 2.5 billion years due to a relatively rapid increase in microorganisms capable of performing photosynthesis. Researchers, including those from the University of Tokyo, provide a mechanism to explain precursor oxygenation events, or "whiffs," which may have opened the door for this to occur. Their findings suggest volcanic activity altered conditions enough to accelerate oxygenation, and the whiffs are an indication of this taking place.

Take a deep breath. Do you ever think about the air entering your lungs? It's mostly inert nitrogen, and the valuable oxygen our lives depend on only accounts for 21%. But this hasn't always been the case; in fact, several mass extinction events correspond to times when this figure changed dramatically. And if you go back far enough, you'll find that before about 3 billion years ago, there was hardly any oxygen at all. So what changed, and how did it happen?

The scientific consensus is that about 2.5 billion years ago, the Great Oxygenation Event (GOE) took place, most likely due to a proliferation of microorganisms exploiting favorable conditions and facing little competition. They would have essentially converted the carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere into an oxygen-rich one, and following that came complex life, which favored this new abundance of oxygen. But it seems there were some precursor oxygenation events prior to the GOE that may indicate the exact nature and timing of changes in the conditions necessary for the GOE to begin.

"Activity of microorganisms in the ocean played a central role in the evolution of atmospheric oxygen. However, we think this would not have immediately led to atmospheric oxygenation because the amount of nutrients such as phosphate in the ocean at that time was limited, restricting activity of cyanobacteria, a group of bacteria capable of photosynthesis," said Professor Eiichi Tajika from the Department of Earth and Planetary Science at the University of Tokyo. "It likely took some massive geological events to seed the oceans with nutrients, including the growth of the continents and, as we suggest in our paper, intense volcanic activity, which we know to have occurred."

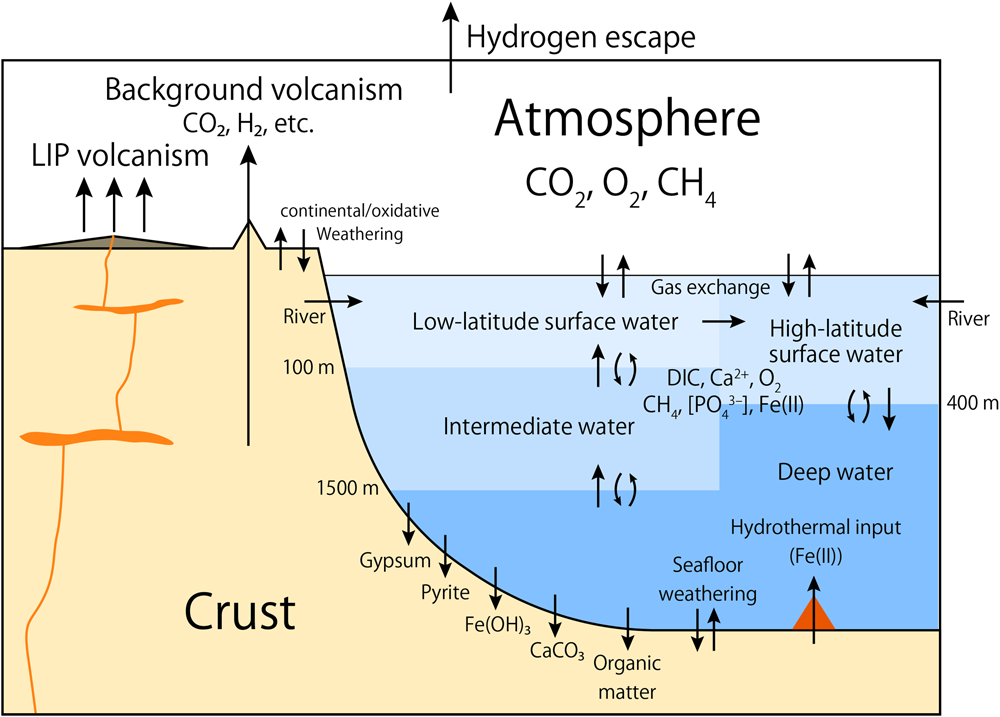

Tajika and his team used a numerical model to simulate key aspects of biological, geological and chemical changes during the late Archean eon (3.0-2.5 billion years ago) of Earth's geologic history. They found that large-scale volcanic activity increased atmospheric carbon dioxide, thereby warming the climate, and increased nutrient supply to the ocean, thus feeding marine life, which in turn temporarily increased atmospheric oxygen. The increase in oxygen was not very steady, though, and came and went in bursts now known as whiffs.

"Understanding the whiffs is critical for constraining the timing of the emergence of photosynthetic microorganisms. The occurrences are inferred from concentrations of elements sensitive to atmospheric oxygen levels in the geologic record," said visiting research associate Yasuto Watanabe. "The biggest challenge was to develop a numerical model that could simulate the complex, dynamic behavior of biogeochemical cycles under late Archean conditions. We built upon our shared experience with using similar models for other times and purposes, refining and coupling different components together to simulate the dynamic behavior of the late-Archean Earth system in the aftermath of the volatile volcanic events."