Walking into Second Chance is like finding 10 different homes all trying to take up the same floorspace. Chandeliers clutter the ceiling, chairs and couches fill the floor, lamps lay claim to spare surfaces. It's a treasure trove of Baltimore artifacts, each well-loved and ready to be resold.

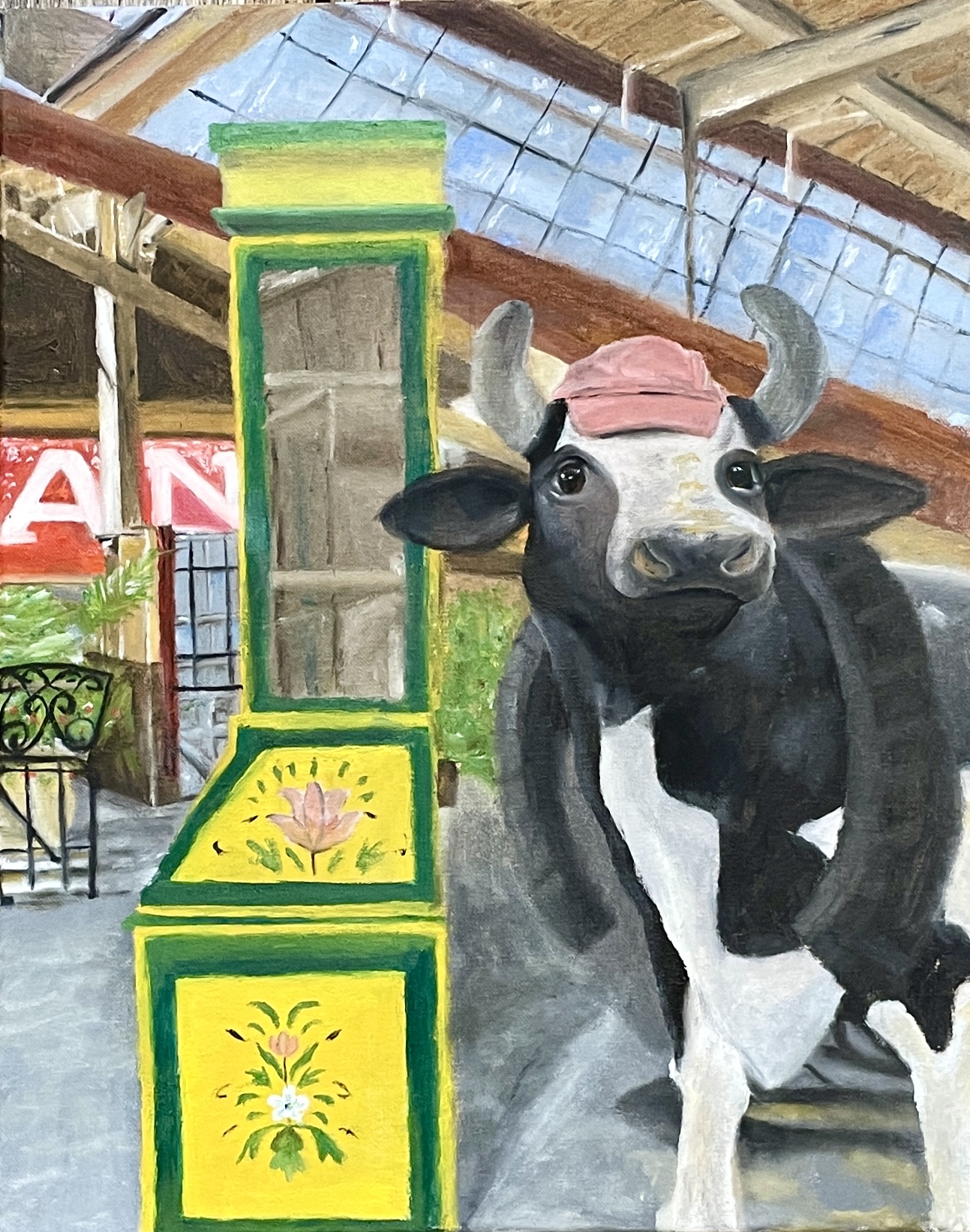

"I saw a cow," says Marcus Hart, a junior at the Peabody Institute. "He was wearing a baseball hat and I was sold. He just drove my creative spirit."

Image credit: Marcus Hart

Hart was among the students who participated in last semester's oil painting classes with Margaret Murphy, director of JHU's Center for Visual Arts. As part of their curriculum, the amateur painters visited Second Chance, a nonprofit that deconstructs old homes and resells the salvaged parts. Shoppers can walk out with everything from a baby grand piano to old growth lumber. Or, if they're taking a class with the Center for Visual Arts, they might find themselves leaving something behind.

For the next month, student pieces from Oil Painting II and III depicting Second Chance furniture will be on display in the non-profit's warehouse. These paintings are joined by photographs of Second Chance workers taken by students in instructor Christiana Caro's documentary photography class. Together, the exhibition captures the nonprofit's eclectic energy, honoring the objects and people of Baltimore.

Although the Second Chance warehouse can be, in Murphy's words, "a bit overwhelming," she feels her students did a fantastic job picking their subjects and compositions.

"This place is just so full of everything imaginable," Murphy says. "In a studio, we deliberately arrange forms to create 'good' compositions based on established rules. However, in the field, we lack this control. Students must become selective observers, searching for compelling arrangements. The assignment takes my students out of their comfort zone, allowing for an experience they can't have in the classroom. Good compositions are everywhere if you are looking."

Video credit: Aubrey Morse / Johns Hopkins University

Murphy first met Second Chance's owner, Mary Blake, in a water aerobics class. After hitting it off, Murphy confessed how much she loved Second Chance, prompting Blake to suggest a collaboration.

From there, it was just a matter of getting all the easels, students, and art supplies from the JHU Film Center to Baltimore's Carroll-Camden Industrial Area.

"Everyone just walked around until they felt a spot that spoke to them," says senior Michelle Nazareth, who painted several cabinets. "You'd turn a corner and there'd be someone painting on the ground."

The assignment helped students hone several of their artistic skills, including composition, perspective, and the ability to paint on-site. But according to Hart, the best takeaway was how Second Chance challenged his and his classmates' creativity.

"Even areas of your life that are kind of unsuspecting ... could be a very beautiful piece of inspiration," Hart says. "Here, it was just random household objects ... and yet there's some of the most difficult compositions that we've created and some of the most diverse. It's pushed everybody in a lot of different directions."

Each still life focused on a different subject, from the building's skylights to its rows of recliners. Many students struck up conversations with the warehouse's associates as they worked, learning about Second Chance's efforts to provide job training and workforce development programs to the Baltimore region.

"We were able to really interact with the space and the people," Hart says. "We were here on days that it wasn't open but [the associates] were working regardless, and they were very interactive with us. I thought that was delightful. There's just a such a sense of community."

Murphy hopes that this assignment inspires her students to spend more time exploring Baltimore, but if nothing else, they now know a great place to find props for their next paintings.

"Most of them had not been here before," Murphy says. "Now [they] know about it and I'm sure will come back."

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University