Australian financial services and credit licensees have an obligation to report breaches to ASIC under the reportable situations regime. ASIC uses this information to identify and address emerging trends of non-compliance and take regulatory action where appropriate.

Reforms to the reportable situations regime in 2021 expanded what was reportable and pushed for more timely and consistent reporting. However, a recent ASIC surveillance shows that there is still more work to do.

We encourage all licensees, not just those in the review, to review their current arrangements for complying with reportable situations against our findings, as well as the better practices we set out, and make the necessary improvements.

ASIC's review

ASIC reviewed the compliance arrangements of 14 licensees of different sectors and sizes who had low numbers of reportable situations, or had not reported at all.

The review looked at:

- the reportable situations these licensees had submitted between October 2021 and June 2024

- their incident registers over a three-month period in 2023, and

- their measures for complying with the regime.

Findings

The review revealed a number of poor practices among licensees:

- Licensees were generally slow to report to ASIC. The key driver of these delays was that licensees took a long time to identify breaches in the first place and begin investigating.

- When ASIC reviewed why this was happening, ASIC found that there were deficiencies in licensees' incident management, particularly how they identified, escalated and recorded incidents.

- Most licensees had gaps in how they monitored their own compliance with the regime.

- These poor practices had real impacts on consumers. The failures to promptly identify breaches meant that licensees were very slow to rectify breaches and remediate customers.

ASIC is seeking compliance outcomes to address these deficiencies from the licensees in the review. We will take enforcement action where appropriate.

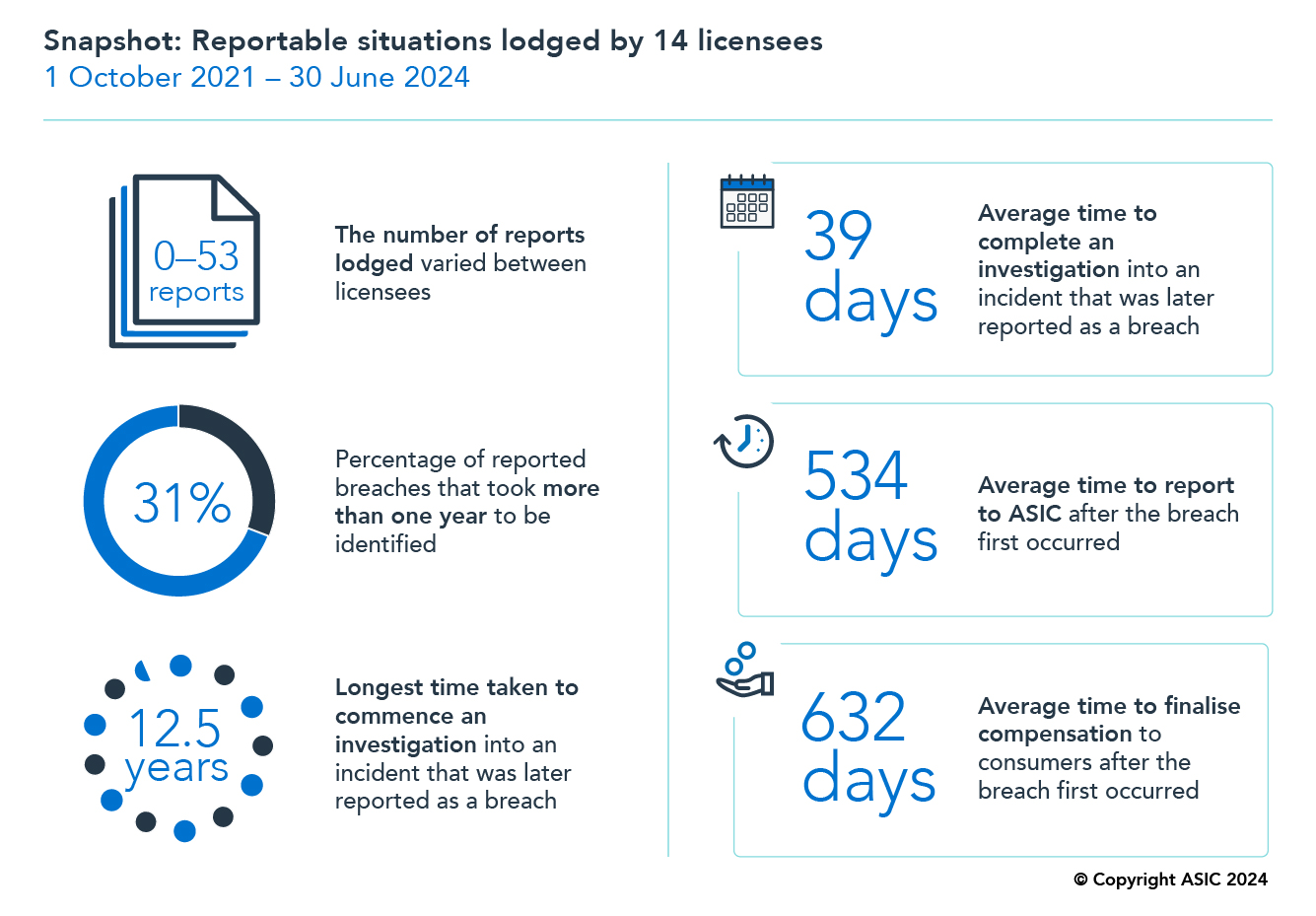

Snapshot: Reportable situations lodged by 14 licensees - text version

1 October 2021 - 30 June 2024

- 0-53 reports the number of reports lodged varied between licensees

- 31% percentage of reported breaches that took more than one year to be identified

- 12.5 years longest time taken to commence an investigation into an incident that was later reported as a breach

- 39 days average time to complete an investigation into an incident that was later reported as a breach

- 534 days average time to report to ASIC after the breach first occurred

- 632 days average time to finalise compensation to consumers after the breach first occurred

Key questions for all licensees

To improve their compliance, licensees should ask themselves the following key questions, and uplift their own arrangements in light of the poor and better practices outlined below.

1. Are you identifying incidents and breaches?

Why this matters

If licensees are not identifying incidents, they cannot assess whether the incidents are breaches or reportable situations. This undermines their ability to comply with the reportable situations regime and their regulatory obligations more broadly.

What we found

Capacity to identify an incident

Poor practice: Most licensees in the review identified and recorded very few incidents - over a three-month period, half of the licensees recorded fewer than five incidents in their incident registers. Even allowing for different sectors, business models and compliance measures, this is very low. It suggests deficiencies in incident identification, which in turn affects breach identification.

Better practice: Licensees should have clear, well-understood and documented processes for identifying incidents and breaches, and make adherence to these a priority. Licensees need to consider how best to monitor their activities so that they can identify incidents and do so in a timely fashion. All licensees are required to have adequate training, resources and systems - including adequate and effective compliance measures and risk management systems to ensure compliance with their licence obligations.

Definition of an incident

Poor practice: Some licensees used complex or restrictive definitions of an incident, while others didn't have a definition at all. Some licensees set high minimum thresholds around financial or other impacts. All these practices reduced licensees' ability to identify incidents.

Better practice: Licensees should establish a simple, broad definition of an incident, written in plain language, and supported by clear guidelines and examples.

Case study: Definitions - simple vs complex

A licensee that recorded a high number of incidents (relative to other licensees in the review) had the simplest and broadest definition:

'An incident is an event that occurs where something has gone wrong.'

In contrast, another licensee's definition was complex and much harder to understand:

'An incident is an event that occurs when the actual outcome of a business objective differs from the expected outcome due to inadequate or failed processes, people, systems or external events which leads to a financial loss or impact on compliance, our customers, employees, operations, information management or brand. A near miss is an event that arises because the control environment failed to detect or prevent the event from occurring. However, due to the circumstances or good fortune, the event does not result in financial or other non-financial impact, but it had the potential to do so'.

Supporting staff

Poor practice: While all licensees placed responsibility on staff members to identify and report incidents, some did not provide adequate guidance to their staff to identify incidents, or to bring them to the attention of breach reporting staff. For some licensees, training on incident identification and handling was provided only at induction, if at all.

Better practice: Licensees should provide regular training to staff to reinforce regulatory requirements and internal policies and procedures. Licensees should maintain a workplace culture where staff are encouraged to be vigilant, raise and escalate incidents, and feel comfortable when doing so.

Incident identification channels

Poor practice: Although all licensees reported that they use several channels to identify incidents and breaches (e.g. staff or business unit reporting, quality assurance, Line 2 or 3 reviews, complaints), some incident registers showed incidents from just one or two sources. For one licensee, almost all recorded incidents were from external sources such as complaints. This likely indicates that their internal channels are not working properly.

Better practice: Licensees should have measures in place to identify, record and escalate incidents and possible breaches from several channels. In addition, licensees should have reporting that enables them to monitor the effectiveness of these arrangements. This should include the volume and distribution of incidents across different channels.

Assessing complaints for incidents and breaches

Poor practice: We saw indications that complaints-handling staff may not be aware of what constitutes an incident or a breach, or how to record and escalate it. Some licensees did not appear to consider that a single complaint may give rise to an incident or a breach and become reportable. Some licensees only reviewed their complaints monthly, which does not support timely incident management. Discussions with some licensees also suggested a risk that they are not adequately identifying and recording complaints in the first place.

Better practice: Licensees should carefully consider whether each customer complaint constitutes an incident, breach or reportable situation. They should also conduct regular root cause analysis to reduce the risk of continuing or reoccurring breaches. Complaints should be interpreted broadly in line with the definition outlined in Regulatory Guide 271 Internal dispute resolution (RG 271).

Case study: A failure to consider the implications of a complaint in a timely way

A licensee received a complaint from a customer who received an annual statement that contained incorrect information. Staff provided the customer with an alternative process to generate a revised statement. Staff did not raise an incident, and there was no investigation into the root cause or wider impact of this issue.

It was not until the licensee had received a further eight complaints that the issue was raised with the head of compliance. This was more than two months after the first complaint was received.

Subsequent investigations revealed the error affected a much larger number of customers - approximately 16% of the licensee's customer base. The licensee then addressed the issue and reported the breach to ASIC. They noted that they had made several changes to their processes, including complaints assessment, because of this incident.

Quality assurance activity

Poor practice: We saw examples where significant time passed before quality assurance activities or file reviews were carried out. This led to delayed identification and also created the risk of ongoing or recurring breaches. In some cases, quality assurance activities appeared limited in scope, with insufficient coverage, making it less likely that incidents or breaches would be identified. Some licensees told us that their quality assurance activities were not risk based, thereby not targeting the riskiest activity or staff members. We also saw indicators that quality assurance was not properly integrated into incident management, breach reporting or the compliance function, reducing the likelihood that learnings would be shared and acted on.

Better practice: Licensees' quality assurance activities should be timely, comprehensive, targeted and well-integrated with the licensee's incident management framework and breach-reporting function. Licensees should 'close the loop', ensuring that identified issues are addressed and learnings shared.

2. Are you escalating and investigating incidents and breaches comprehensively and in a timely way?

Why this matters

Timely escalation and, where necessary, investigation supports the regime's objectives, which are prompt rectification and remediation of issues, and reporting to ASIC. Timely escalation and investigation also reduces the risk of incidents or breaches continuing or reoccurring, and helps the root cause of an incident or breach to be identified quickly.

What we found

Recording, escalating or acting on incidents and breaches

Poor practice: Some incident-handling frameworks likely contributed to overall delays. For example, timeframes that were excessively long or poorly defined, such as asking staff to act 'as soon as possible' after they had identified an incident. It was not clear that licensees monitored timeframes and acted on delays, which indicates a level of acceptance for internal non-compliance.

Better practice: Licensees should have defined timeframes across the incident and breach life cycle. Timeframes should be clear and suitably short. Adherence to timeframes should be monitored and reported on. If an investigation is necessary, it should start immediately, and not be delayed while an issue is being rectified.

Case study: Delays in escalation

A licensee's incident management process was not designed to support timely escalation and resolution.

- Line 1 staff had 14 days to record incidents from when they were first identified.

- Line 1 assessment staff then had 21 days to determine if an incident should carry a compliance flag and be considered by the Line 2 compliance team.

- The Line 2 compliance team responsible for breach reporting then had a further seven days to start an initial investigation.

Based on the timeframes, more than a month could pass before an incident was brought to the attention of the breach reporting team to start an investigation into whether a breach or likely breach had occurred and was significant, and up to 42 days could pass from the date of incident identification before they started their investigation.

Based on an analysis of their reportable situations, this licensee took on average 487 days from the first instance of the breach to commence an investigation.

3. Do you capture important information about incidents and breaches in a single register?

Why this matters

A detailed and mandatory register of incidents and breaches prompts licensees to gather relevant information and conduct thorough investigations. Maintaining a single, comprehensive register helps licensees to understand the nature of their incidents and breaches and to capture necessary insights. It also helps licensees to monitor for systemic issues and the number and frequency of similar breaches.

What we found

Quality of incident and breach registers

Poor practice: Some registers contained little or no information on key aspects of incidents and breaches such as what had happened, critical timeframes, losses incurred, customers affected or the root cause. Other licensees recorded these details across multiple registers or documents. Some licensees did not record all incidents, telling us they relied on staff discussions to resolve incidents, and did not document decisions. These practices make it more difficult to demonstrate compliance. They also make it less likely that the licensee will conduct a full investigation and root cause analysis.

Better practice: To ensure that licensees can satisfy themselves that they have done all things necessary to properly identify, record and report to ASIC reportable situations, including systemic breaches, licensees' breach registers should contain the information in the reportable situations prescribed form (summarised in Table 8 of Regulatory Guide 78 Breach reporting by AFS licensees and credit licensees (RG 78)).

4. Have you got the necessary arrangements in place to monitor your compliance with the regime?

Why this matters

Monitoring compliance helps licensees ensure that they meet legal obligations and respond to regulatory changes. Proactively monitoring and tracking compliance allows licensees to identify and mitigate risks of non-compliance that may result in costly legal issues, reputational damage and consumer losses. Regular monitoring of activities that span the whole breach life cycle will give senior management the oversight to ensure compliance arrangements remain effective.

What we found

Reporting to senior management

Poor practice: In many cases, there was limited reporting of incidents and breaches to senior management. Examples of inadequate reporting included providing only a one-line description for each reportable situation lodged, or providing no description at all. Another example involved only minimal information on the volume and type of incidents and their status. These practices prevent proper scrutiny of incident management and breach reporting.

Better practice: Licensees should have robust governance and accountability structures around their breach reporting obligations, supported by reporting that promotes information and intelligence sharing to senior management. Licensees should regularly monitor, benchmark and internally report on the number of incidents and breaches, any trends, and timeliness across the various stages of incident management. Reporting should include analysis of root causes and systemic issues, to enable management to proactively detect significant or emerging issues and ensure that existing issues are adequately addressed.

Reviews into compliance

Poor practice: Several licensees only conducted a review into their compliance after being prompted by ASIC to do so. Some had not undertaken a review at all, but had reviews scheduled. Where licensees did a review, many simply looked at their policies and procedures, and did not consider the effectiveness of the breach reporting function in practice or look at the end-to-end breach reporting cycle (including incident management).

Better practice: Licensees should conduct regular reviews or audits of the entire breach-reporting cycle, and test compliance arrangements in principle as well as the actual outcomes of those arrangements.

Background

ASIC conducted a review of the policies, processes and practices that 14 licensees had in place to comply with their reportable situations obligations under s912DAA of the Corporations Act 2001 and/or s50B of the National Credit Consumer Protection Act 2009, as at November 2023. We met with licensees for an extensive discussion of their arrangements in the quarter ending June 2024. We reviewed licensees' incident registers for the three-month period from July to September 2023. We also reviewed all reports lodged by licensees from 1 October 2021 to 30 June 2024.