The universe has been expanding ever since the Big Bang almost 14 billion years ago, and astronomers believe a kind of invisible force called dark energy is making it accelerate faster.

Author

- Rossana Ruggeri

Lecturer and ARC DECRA Fellow, Queensland University of Technology

However, new results from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), released today, suggest dark energy may be changing over time.

If the result is confirmed, it may overturn our current theories of cosmology - and have significant consequences for the eventual fate of the universe. In extreme scenarios, evolving dark energy could either accelerate the universe's expansion to the point of tearing it apart in a "Big Rip" or cause it to collapse inward in a "Big Crunch".

As a member of the DESI collaboration, which includes more than 900 researchers from 70 institutions worldwide, I have been involved in the analysis and interpretation of the dark energy results.

A new picture of dark energy

First discovered in 1998 , dark energy is a kind of essence that seems to permeate space and make the universe expand at an ever-increasing rate. Cosmologists have generally assumed it is constant: it was the same in the past as it will be in the future.

The assumption of constant dark energy is baked into the widely accepted Lambda-CDM model of the universe. In this model, only 5% of the universe is made up of the ordinary matter we can see. Another 25% is invisible dark matter than can only be detected indirectly. And by far the bulk of the universe - a whopping 70% - is dark energy.

DESI's results are not the only thing that gives us clues about dark energy. We can also look at evidence from a kind of exploding stars called Type Ia supernovae, and the way the path of light is warped as it travels through the universe (so-called weak gravitational lensing).

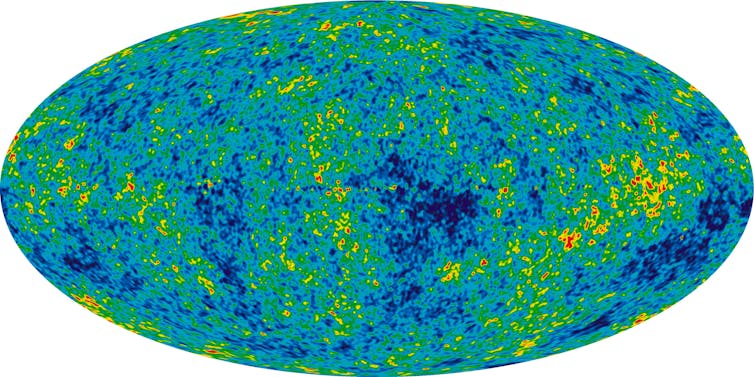

Measurements of the faint afterglow of the Big Bang (known as the cosmic microwave background) are also important. They do not directly measure dark energy or how it evolves, but they provide clues about the universe's structure and energy content - helping to test dark energy models when combined with other data.

When the new DESI results are combined with all this cosmological data, we see hints that dark energy is more complicated than we thought.

It seems dark energy may have been stronger in the past and is now weakening. This result challenges the foundation of the Lambda-CDM model, and would have profound implications for the future of the universe.

How DESI maps the universe

The DESI project is based at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona. Its goal is to create the most extensive 3D map of the universe ever made.

To do this, it uses a powerful spectroscope to precisely measure the frequency of light coming from up to 5,000 distant galaxies at once. This lets astronomers determine how far away the galaxies are, and how fast they are moving.

By mapping galaxies, we can detect subtle patterns in their large-scale distribution called baryon acoustic oscillations. These patterns can be used as cosmic rulers to measure the history of the universe's expansion.

By tracking these patterns over time, DESI can map how the universe's expansion rate has changed.

DESI is only halfway through a planned five-year survey of the universe, releasing data in batches as it goes.

The new results are based on the second batch of data, which includes measurements from more than 14 million galaxies and brightly glowing galactic cores called quasars. This dataset spans a cosmic time window of 11 billion years - from when the universe was just 2.8 billion years old to the present day.

New data, new challenges

The new DESI results represent a major step forward compared with what we saw in the first batch of data. The amount of data collected has more than doubled, which has improved the accuracy of the measurements and made the findings more reliable.

Results from the first batch of data gave a hint that dark energy might not behave like a simple cosmological constant - but it wasn't strong enough to draw firm conclusions. Now, the second batch of data has made this evidence stronger.

The strength of the results depends on which other datasets it is combined with, particularly the type of supernova data included. However, no combination of data so far meets the typical "five sigma" statistical threshold physicists use as the marker of a confirmed new discovery.

The fate of the universe

Still, the fact this pattern is becoming clearer with more data suggests that something deeper might be going on. If there is no error in the data or the analysis, this could mean our understanding of dark energy - and perhaps the entire standard model of cosmology - needs to be revised.

If dark energy is changing over time, it could have profound implications for the ultimate fate of the universe.

If dark energy grows stronger over time, the universe could face a "Big Rip" scenario, where galaxies, stars, and even atoms are torn apart by the increasing expansion rate. If dark energy weakens or reverses, the expansion could eventually slow down or even reverse, leading to a "Big Crunch".

What's next?

DESI aims to collect data from a total of 40 million galaxies and quasars. The additional data will improve statistical precision and help refine the dark energy model even further.

Future DESI releases and independent cosmological experiments will be crucial in determining whether this represents a fundamental shift in our understanding of the universe.

Future data could confirm whether dark energy is indeed evolving - or whether the current hints are just a statistical anomaly. If dark energy is found to be dynamic, it could require new physics beyond Einstein's theory of general relativity and open the door to new models of particle physics and quantum gravity.

![]()

Rossana Ruggeri is part of the DESI Collaboration. She receives funding from her ARC DECRA grant. She is affiliated with QUT and UQ.