Recall germinal centers formed in response to a secondary infection generate a second line of defense, rebuffing memory B cells in favor of training naive ones.

Certain infectious diseases, such as COVID or the flu, evolve constantly, shapeshifting just enough to outmaneuver our immune systems and reinfect us repeatedly. But subsequent reinfections often don't lead to the most severe outcomes-for very good reason. Upon first exposure to a pathogen, our immune systems churn out specially trained B cells, which have learned to identify and eliminate the virus. Later, those B cells remain primed and ready to produce powerful recall antibodies.

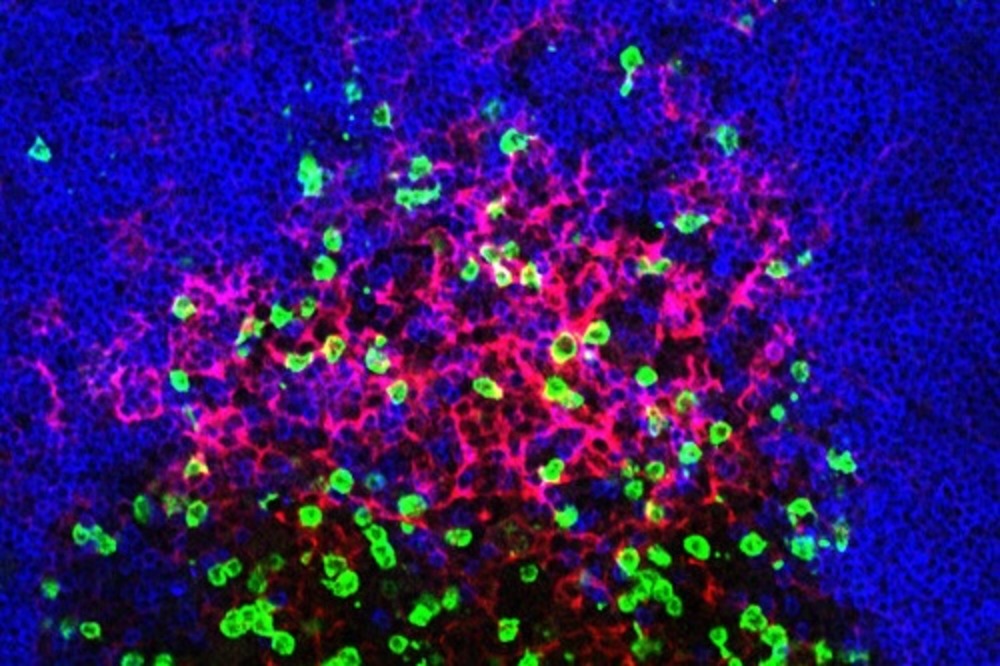

Scientists long thought that the body ultimately cleared these types of infections essentially by getting old immune cells up to speed: refining those previously trained in germinal centers, which are the specialized structures in our lymph nodes and spleen where B cells learn to identify and eliminate threats. But recent work suggests that "recall germinal centers"-those formed upon re-exposure-are actually generating a different, second line of defense. By drawing heavily on naive and untrained B cells, these reactivated centers focus on developing entirely new antibodies, while the experienced B cells spring directly into action.

A new study in Immunity explains how this two tiered system benefits the immune response, with results that have implications for vaccine boosting strategies.

"We investigated the underlying principles that explain how the body responds to repeat exposures, whether to a vaccine or virus, and how recall germinal centers shape that response," says first author Ariën Schiepers, a graduate student in the laboratory of Gabriel Victora.

For the study, Victora, Schiepers, and colleagues examined mice repeatedly immunized with the same antigen and assessed the antigen-binding abilities of recall B cells. What they discovered was that existing antibodies, derived from B cells that had weathered the first infection, were actively preventing B cells with overlapping specificities from entering recall germinal centers. And when they boosted mouse models with variants of the original virus, they found out why this system makes sense. In response to a viral variant, the recall germinal centers were guiding naive B cells toward the new antigenic target. This prevents the immune system from investing in B cells from a prior infection-and repeatedly churning out antibodies that target a bygone virus.

"It's an elegant feedback system, with antibodies generated in the first response aiding in shaping new antibodies toward the variant," Schiepers says. "Recall germinal centers are like librarians adding new titles to the immune system's library, ensuring it does not just retrieve the same old book again and again."

The findings suggest implications for booster shots. While traditional boosters work well for childhood vaccines by increasing antibody levels, the approach becomes more complex with evolving viruses. Boosting with a variant antigen may reduce overlap with previous antibodies and allow the immune system to better target new variants. "This demonstrates exactly why there's a real advantage in boosting against a variant," Schiepers says.