If you have a sore shoulder, physical therapy is likely to make you feel better. But traditionally, it has been difficult for physical therapists to quantify exactly how much better a patient gets.

Now imagine you enter a clinic, and after describing your symptoms and having an exam, the physical therapist shows you a graph charting the progress of people with the same condition. The curve's trajectory details how you will improve and how many sessions it will take based on data from hundreds or thousands of patients who share your profile.

Patients in the Sargent College of Health & Rehabilitation Science BU Physical Therapy Center at the Ryan Center for Sports Medicine & Rehabilitation have started receiving such personalized charts. It's part of a quest for sharper, data-fueled insights into patient outcomes. Since September 2016, the clinic has been working with the Rehab Outcomes Management System (ROMS), a database and analysis software program developed by clinicians at Intermountain Healthcare in Utah. BU was one of the first institutions in the country to adopt the commercial version of ROMS. The system does for physical therapy what analytics has done for sports management (think of the movie and book Moneyball): using statistical evidence to drive decisions. Now, the BU facility, a Sargent clinical education center that operates independently and is open to the public, is using data to inform decisions on clinical approaches to common ailments, pursue new lines of research, and update the best practices taught to Sargent students.

"It helps us accurately track patient progress and help get people better faster," says James Camarinos, director of the center, which averages 2,200 new patients every year and around 25,000 physical therapy sessions annually.

With ROMS, BU clinicians collect information from patients about how they feel at every visit using standardized questions based on a patient's condition: patients with neck pain would be asked, for example, about the intensity of their pain and whether they experience discomfort bathing and dressing. The program turns their answers into data that clinicians can analyze to study the efficacy of treatment approaches for common ailments and make more precise predictions about outcomes, which can help set the right expectations for a patient experiencing pain.

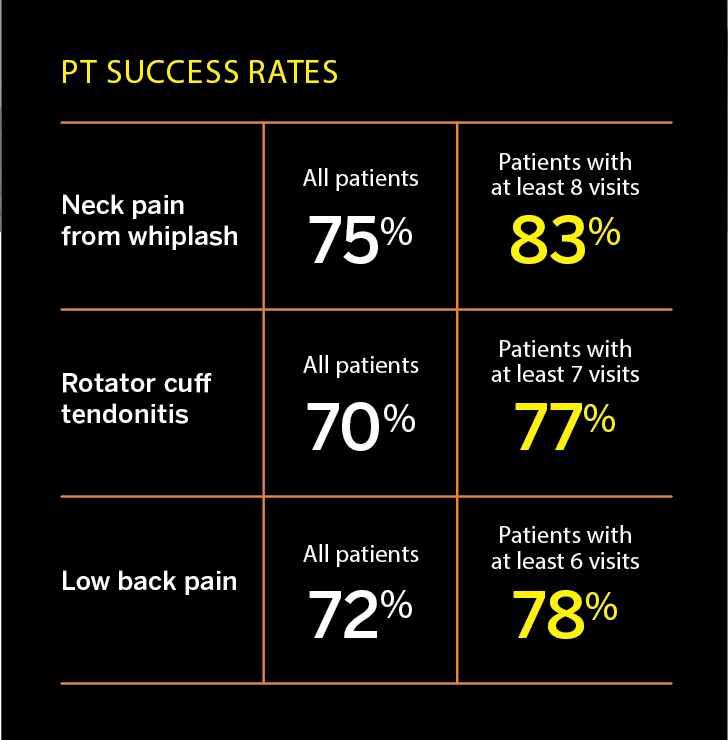

"If you come to our clinic for rotator cuff tendonitis, there's a likelihood of success of 70 percent on the outcomes we use, and these are a good proxy of everyday function," says Camarinos. But delving into the data further shows that for those who average seven visits, the chance of success rises to 77 percent. It's a way to convey to patients the benefits of sticking with physical therapy after the first few visits to the clinic. "We're making that statement not just based on experience alone," he says, "which is of course highly valuable, but also based on data science."

That opportunity to use data analysis to ask new questions about the effectiveness of physical therapy treatments is especially important at a time when healthcare providers are looking to find cost-effective ways to deliver quality results, says Lee Marinko (Sargent'08), a Sargent clinical associate professor of physical therapy and athletic training.

Prior to the adoption of ROMS, information about how patients felt was incomplete and imprecise, Marinko says. "The problem with not collecting standardized outcomes is that everybody gets better when they go to physical therapy, because they just feel better. But what is it about what we do that really makes them better?"

Traditionally, physical therapists used patient satisfaction scores, as well as measurements of physical impairment, like the range of motion in a knee or shoulder. Through such measurements, a therapist could discern improvements. But the quality of such readings was variable: different physical therapists asked different questions, for instance, and they did not ask them at every visit.

Today, says Marinko, BU's clinicians can analyze data they collect to identify factors that could improve care and compare the experiences of their patients to others with the same conditions nationwide. One project that Marinko and her colleagues are pursuing, for example, is studying how long it takes for a patient to see a physical therapist after calling the clinic, and correlating that answer with patient results. How much difference can it make to get a patient into sessions right away? The new data will help answer that question.

Another question is about patient copayments. "Insurance copayments have changed dramatically, with more of the burden coming to the patient," says Marinko, who is also a clinician at the center. "If you have to pay more, do you come for fewer visits and therefore not get as good of an improvement?"

With six Ryan Center physical therapists also holding teaching positions at Sargent and students often completing internships at the center, advances pioneered in the clinic quickly find their way into the classroom-and vice versa. Marinko points to a ROMS analysis that identified risks in certain patients who should be referred to a doctor to reduce the chance they will suffer a prolonged disability. The insights led to better, more personalized care and in turn, have informed the best practices Marinko teaches her students.

"The data allow us to ask questions to improve care and then change the way we teach our students," Camarinos says. "It's an established thing in medicine, that we know that it can take up to 17 years to get a new discovery into real-life practice. We hope to shrink that timeline."