In Florida, as little as 15 percent of the unique ecosystem known as the Florida scrub remains due to human land use. The ecosystem, which occurs in sandy patches throughout the state, has the highest number of endemic species—those found nowhere else in the world—in the southeastern United States. Many of the endemic plants are now endangered species.

As part of an effort to protect the Florida scrub, biologists in the University of Miami's College of Arts and Sciences are studying how microbes that live in its soil can impact the health and distribution of native plants. The plants include highlands scrub hypericum (Hypericum cumulicola), wedge-leaved button-snakeroot (Eryngium cuneifolium), and Florida jointweed (Polygonella basiramia), all of which are listed as federally endangered species.

"Our goal is to try to understand why plant species occur in different places on the Florida landscape and how much of that is driven by the soil microbiome," explained Michelle Afkhami, an associate professor of biology and one of the principal investigators of the study, which is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF). "A fundamental question in ecology is: Why do species occur where they do? This matters a lot because if you're trying to predict what will happen with climate change or other human impacts in a changing world, you need to understand what factors are driving why species are where they currently are."

A better understanding of the microbiome could aid in efforts to conserve and restore the Florida scrub. Many people are familiar with the idea of microbes living in the human body, but microbes exist almost everywhere, including in plants, Afkhami explained.

To measure the impacts of the soil microbiome, the team collected soil samples from 30 different patches of Florida scrub at the Archbold Biological Station, a field research station located about 140 miles northwest of Miami. Each patch has different environmental features, which the scientists believe have created different microbial characteristics. In the University of Miami Greenhouse, the researchers have planted native plant species in pots containing these differing microbiomes. By comparing the growth of plants with and without different soil microbiomes, the team aims to measure the effects of the microbes.

"We've found that the microbiome is actually really important for the persistence of plant species on the landscape, so if you alter the microbiome, you could be impacting whether these species can persist," Afkhami said.

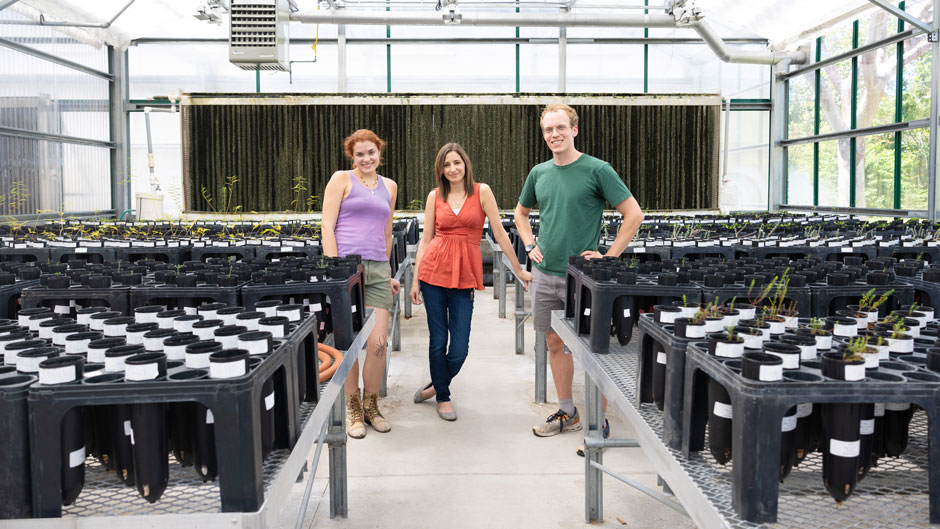

The study is a collaboration between Afkhami and Christopher Searcy, an associate professor of biology, along with Joshua Fowler, a postdoctoral research associate, and Gwen Pohlmann, a post-baccalaureate research associate.

This research has also spurred a related study, led by Fowler, that focuses on microbes in soil that is found in former citrus groves. The sandy, well-drained soils of the Florida scrub, which support so many native plants, also provide ideal conditions for citrus trees. In the past, Florida's citrus industry converted this habitat into groves. Yet today, with the citrus industry declining, conservationists want to restore the Florida scrub.

Fowler's research compares microbes in soil from the Florida scrub to microbes from active and fallow citrus groves to evaluate how the citrus groves impact the microbiome.

"People are starting citrus restoration and thinking about how we can steer soil microbiomes toward something that would better support the performance of native plants and biodiversity in general," Fowler explained.

To pursue this study, Fowler was recently awarded the Archbold Biological Station's David S. Maehr Florida Wildlife Corridor Applied Science Fellowship, which is made possible through the support of Bellini Better World. The study is part of a broader effort to conserve a wildlife corridor that connects native habitats across Florida. Fowler is collaborating with researchers from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and the Archbold Biological Station, as well as private landowners.

The studies in the University greenhouse are not the only ones in the Department of Biology that may help to restore some of Florida's natural habitats. Other researchers are actively involved in studies that have implications for environmental protection.

"There is a lot of interesting research going on throughout the department that's trying to address this reality of human and natural ecosystems co-occurring and how we restore habitats," Afkhami said. "A lot of the ecosystems in South Florida have amazing, unique biodiversity, but also are highly imperiled because we have such large human populations."