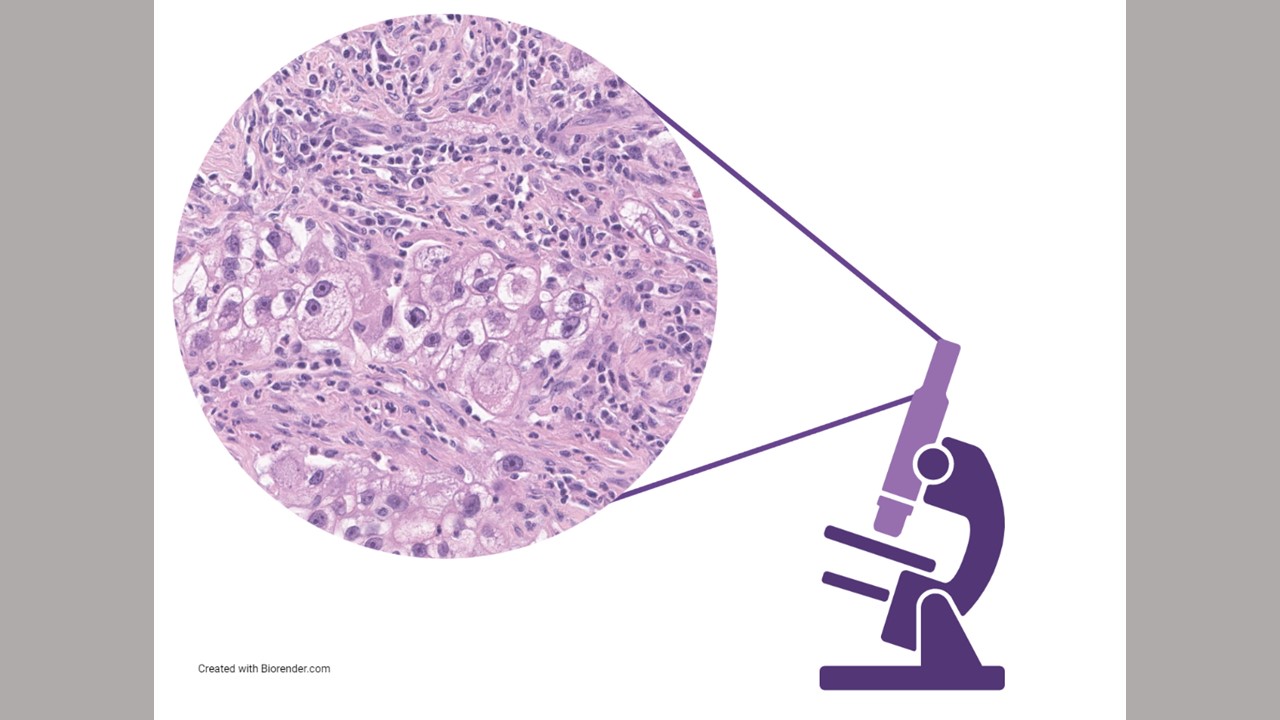

Pathologists look through a microscope to evaluate H&E slides for tumor infiltrating immune cells and necrosis in patients with kidney cancer who go on to receive immunotherapy. Credit: Julie Stein Deutsch via Biorender

The number of immune cells in and around kidney tumors, the amount of dead cancer tissue, and mutations to a tumor suppressor gene called PBRM1 form a biomarker signature that can predict - before treatment begins - how well patients with kidney cancer will respond to immunotherapy, according to new research directed by investigators at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and its Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy.

In reviews of 136 kidney tumor biopsies taken for previous studies, investigators found that patients who had three positive factors - presence of immune cells in and around tumors, known as tumor-infiltrating immune cells, absence of dead cancer tissue, called necrosis, and a mutation in the PBRM1 gene - had the best overall survival at five years compared with patients who did not have this combination of factors. A report about the work was published online Feb. 21 in the journal Cell Reports Medicine.

Therapies for patients with metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma, a type of kidney cancer, are rapidly evolving and include immunotherapy-based regimens, says lead study author Julie Stein Deutsch, M.D., a clinical fellow in dermatopathology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. However, there is an unmet need for biomarkers that can help match patients to the regimens most likely to help, she says. Such markers have been investigated in lung and other cancers, but have not shown the same predictive ability in patients with kidney cancers.

The classic hematoxylin and eosin-stained (H&E) pathology slide - the gold standard for diagnosing and staging cancer in medical practices worldwide - has largely been overlooked as a possible source of biomarker information, Deutsch says. "There are many studies investigating biomarkers for response to immunotherapy using advanced technologies that require expensive machines and experienced technicians. The ability to use information from an H&E slide, pretreatment, to predict overall survival of patients receiving this therapy is extremely powerful, and is something that can be used in resource-poor settings as well," she says.

Immunotherapies that target PD-1 (programmed cell death 1), a protein found on immune cells, can unleash an immune response against cancer cells and has become a vanguard of cancer therapy, says senior author Janis Taube, M.D., M.Sc., co-director of the Tumor Microenvironment Laboratory at the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy and director of the Division of Dermatopathology. However, she points out that anti-PD-1 immunotherapies do not work in all patients. The new findings could be used to help preselect patients for the most appropriate therapy, says Taube.

Investigators examined H&E slides from 136 metastatic tumor samples, before treatment, from patients with renal cell cancers to determine the biomarker potential of this commonly available material. They reviewed 63 biopsies obtained before treatment from patients who received the immunotherapy nivolumab as a first cancer treatment or later treatment; 58 biopsies from patients receiving later-line nivolumab or the chemotherapy drug everolimus; and 15 biopsies from patients who hadn't received therapy before, who received nivolumab plus the immunotherapy ipilimumab. Researchers scored the specimens for the amount of tumor-infiltrating immune cells (here called TILplus) and presence of necrosis (dead tissue).

In the first group of 63 biopsies, and in samples from all three groups of patients who received immunotherapy, patients with specimens that had immune infiltrates (e.g., tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells) interfacing with tumor (TILplus score of 1) showed improved overall survival compared with those without (i.e., specimens with TILplus score of 0). Median overall survival was 47.9 months in those with a TILplus score of 1 versus 16 months in those with a score of 0. Median progression-free survival was 7.5 months in those with a TILplus score of 1 versus 2.7 months in those with a score of 0. However, TILplus score was not associated with overall survival among patients receiving everolimus, indicating the findings were specific to immunotherapy.

The presence of necrosis was found to modify the benefits of having immune system infiltration in the tumor. In two groups of biopsies studied, patients whose tumors had substantial necrosis (greater than 10% surface area) had lower overall survival compared with patients who had the same TILplus score but whose tumors lacked necrosis. This finding was observed in patients from two cohorts. Again, combining TILplus and necrosis scores was not predictive of outcomes for patients receiving everolimus.

"This is important, because traditionally, areas of necrosis are often excluded from biomarker studies because it can't be used for genomic or transcriptomic studies since the tissue is dead," Deutsch says. "We show there is important information in that necrotic area that's conferring some sort of negative disadvantage to patients. It's important not to overlook these areas when you're investigating biomarkers that predict how patients are going to do."

Finally, investigators looked at mutations in the PBRM1 gene and how that impacts the other factors. Such mutations were correlated with overall survival but were not associated with TILplus. However, a statistical analysis of all three factors found that the combination of H&E scoring with PBRM1 mutation status stratified patients into three groups. Patients who had all three positive factors - a TILplus score of 1, necrosis score of 0 and a PBRM1 mutation - had the best overall survival at five years. Patients with two of the three features demonstrated intermediate survival, while those with only one feature had the worst survival.

When investigators performed a literature search, they were unable to find other studies that used H&E features as part of tumor characterization using multimodality approaches. "This demonstrates the underutilization of these insights in biomarker discovery for immunotherapies," Deutsch says.

Taube says next steps will include validating the findings in larger groups of patients and potentially prospectively in a clinical trial.

In addition to Taube and Deutsch, study co-authors were Evan J. Lipson, Ludmila Danilova, Suzanne L. Topalian, Jaroslaw Jerdych, Ezra Baraban, Yasser Ged, Nirmish Singla, Toni K. Choueiri, Saurabh Gupta, Robert J. Motzer, David McDermott, Sabina Signoretti and Michael Atkins. Other institutions participating in the research were Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and the Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in Washington, D.C.

The work was supported by The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research, Bristol-Myers Squibb, a Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center Core Grant (P30 CA006973), the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA142779), the National Institutes of Health (grants T32 CA193145 and R50 CA243627), Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Kidney SPORE (2P50CA101942-16 and Program 5P30CA006516-56), the Kohlberg Chair at Harvard Medical School and the Trust Family, Michael Brigham, Pan Mass Challenge, Hinda and Arthur Marcus Fund, Loker Pinard Funds for Kidney Cancer Research at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy.

Taube reported grants and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Akoya Biosciences, consulting for Merck, AstraZeneca, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Regeneron, Lunaphone and Compugen outside this work. Deutsch and Taube filed an institutional patent on machine learning for scoring pathologic response to immunotherapy. These relationships are managed by The Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.