On the day that 13-year-old James collapsed, he gave his parents, Bryan and Anne Gast, a hug and a kiss and headed to his first-period class. It was an ordinary day in April 2022.

But minutes later, his parents heard the devastating news.

"Children came to tell us that James was joking around and that he had slammed his head on the ground while trying to jump a bench," said Bryan Gast, who teaches science. "He wasn't conscious."

Bryan and Anne were with their son immediately. They both work at the school, where James attended seventh grade.

Someone called 911. The next thing they knew, an ambulance was transporting James to UC Davis Children's Hospital.

A CT scan would reveal what actually happened to James that morning: He had bleeding in his brain due to a ruptured aneurysm (a weakened area of a blood vessel). James hadn't jumped a bench at all. He had just collapsed, slumping over a bench.

James's neurosurgeon, Ben Waldau, describes it in medical terms: James had a ruptured anterior communicating artery (ACOM) aneurysm. The aneurysm was partially thrombosed, which means a blood clot had formed inside the cerebral artery, restricting blood flow. The aneurysm was giant, more than 25 millimeters, the diameter of a quarter coin. James needed treatment.

"I was shocked more than anything. The thing that hit us most was when one of the neurosurgeons told us that he would be in the intensive care unit for the next month. We were not prepared," Anne said.

Preparing for surgery

There were no signs or symptoms beforehand that James had anything wrong with his brain. He was healthy and had never had headaches. He had no genetic predispositions that they were aware of.

But their previously healthy son had brain surgery scheduled for the next morning.

"He was sedated, intubated on a ventilator, and they gave him a lot of medication so his blood pressure stayed low. Then it was just a waiting game, hoping he would make it through the night," said Bryan.

Waldau had hoped he could clip the aneurysm, a type of microsurgery in which a metal surgical clip is used to close off an aneurysm in the brain. But he wouldn't know what was possible until James was on the operating table. And then, Waldau faced another challenge.

"I could not initially approach the aneurysm because the intracranial pressure was elevated, and his brain was significantly swollen. The swelling blocked the surgical corridor to the aneurysm," Waldau said.

Additional medication and changes in head positioning were required to help bring the swelling down to make the approach possible.

"We used our standard brain relaxation techniques. Then we were able to perform a microsurgical clipping of the aneurysm," Waldau said.

But James was not out of the woods. After the surgery, James developed weakness on the left side of his body, and his brain continued to swell, which can lead to damage and even death if left untreated.

"They needed to give his brain a chance to relax and his brain couldn't do that within the confines of his skull," said Bryan.

James underwent a hemicraniectomy, an operation in which a section of the skull is removed, for high intracranial pressure. The operation was successful. A cranioplasty would be conducted about two months later, a surgery in which pediatric neurosurgeon Marike Zwienenberg replaced his skull once the swelling receded.

The road to recovery

The next seven weeks were dedicated to James's recovery in the hospital.

James had goals to meet: He would need to be weaned off his medication and taken off of the ventilator. He would need to relearn how to swallow, talk, walk, and strengthen his left side.

Rehab began with the UC Davis inpatient team. He received more than three hours of speech, occupational and physical therapy each day.

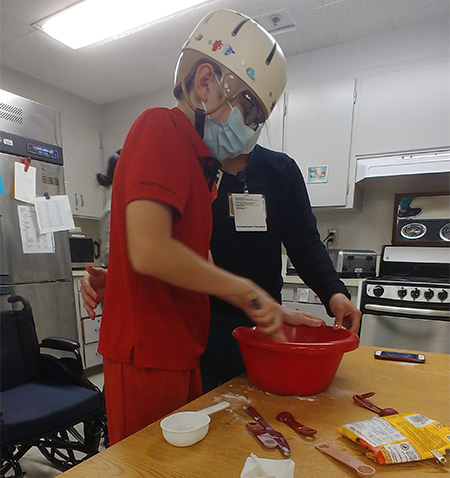

Physical therapy consisted of time in the gym and walks outside. In occupational therapy, he worked on his left visual field and strengthened his left arm and hand for completing the activities of daily living.

"He enjoyed playing games that targeted his attention, problem-solving and memory," remembered James's speech therapist Michelle Ramirez. "James progressed steadily and made great improvements."

Anne and Bryan spent their days at the hospital, listening in on daily rounds with James's care team.

"They did a good job of answering our questions and providing their rationale for their decisions," said Anne. "And the team took good care of us. His nurses would sit with us and check in to see how things were going."

By May 25, after 52 days of hospitalization, James was able to return home.

A bright future ahead

James has continued to make great strides, relearning to ride a bike and taking piano lessons. He has gone back to the rock-climbing gym, a pastime he enjoyed before his world changed so drastically.

He was able to return to school full-time for his eighth-grade year. He participated in his school's holiday performance of "It's Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas," singing and dancing with his classmates. Those watching the holiday scene would never know that James had overcome so many challenges to be there.

James continues to have regular neurosurgery check-ins with Waldau. His family still stays in touch with members of his care team.

"I look forward to updates from Anne about James's performances, promotions and his chance for new 'firsts' — getting out of bed without a helmet, first swim, first time riding a bike, first day of school," Ramirez said. "James is an inspiration to all who know and have worked with him. His parents made his immense progress possible through their advocacy and support."