An interdisciplinary study led by the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) reveals that women living in the region of Nubia (present-day Sudan) developed skeletal changes adapted to bearing heavy loads on their heads starting in the Bronze Age over 3500 years ago. The results, published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, shed light on a largely invisible practice that has been ignored by written history and which has been carried out primarily by women for millennia.

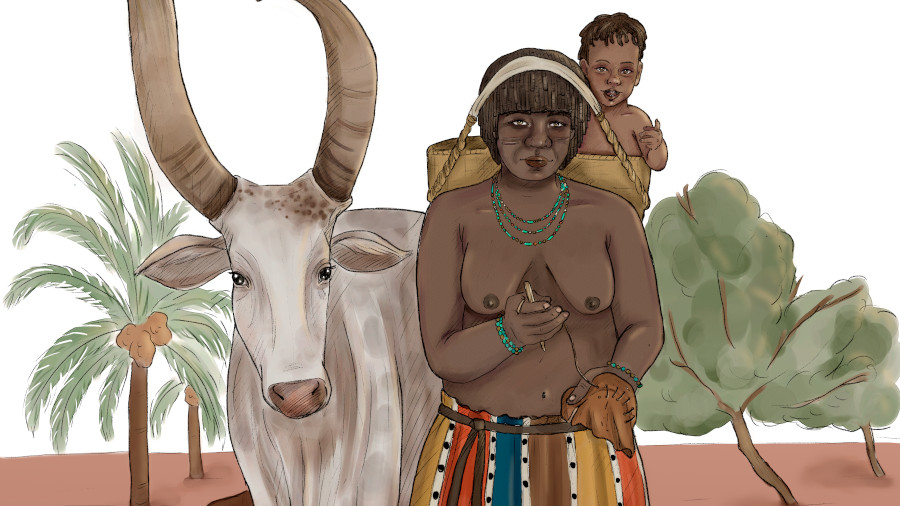

For generations, the most common images of physical labour in prehistory have been dominated by depictions of men. However, a recent study published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology challenges this male-centered view: in what is now Sudan, more than 3,500 years ago, Nubian women from the Kerma culture (2500-1500 BCE) were already carrying heavy objects — and sometimes even children — on their heads daily, using techniques passed down through generations, such as head straps known as tumplines.

The research, led by Jared Carballo from the UAB Department of Antiquity and Middle Ages Studies and affiliated to Leiden University in the Netherlands, and Uroš Matić from the University of Essen, Germany, combines the anthropological analysis of skeletal remains with ethnographic and iconographic studies of various African and Mediterranean cultures, including representations of Nubian women in Egyptian tombs. The aim of the study was to understand how daily labour shapes the body and how load-carrying tasks were distributed between men and women.

The study of 30 human skeletons (14 women and 16 men) buried at the Bronze Age site of Abu Fatima, located near Kerma, the capital of the kingdom of Nubia – also called Kush and a rival of ancient Egypt –revealed significant sex-based differences, thanks to the material provided by the excavations by the Sudanese-American Mission led by Sarah A. Schrader and Stuart T. Smith, co-authors of the research. While men showed signs of strain in the shoulders and arms, especially on the right side — likely from shoulder-carrying — women exhibited specific skeletal changes in the cervical vertebrae and areas of the skull associated with the prolonged use of head straps that transferred weight from the forehead to the back.

One of the clearest examples was the woman classified as "individual 8A2": a woman who died over the age of 50 and was buried with luxury items such as an ostrich feather fan and a leather cushion. Biochemical analysis of her dental enamel indicates she was born elsewhere, suggesting she was a migrant. Her skull displays a significant depression behind the coronal suture and severe cervical osteoarthritis, consistent with a prolonged use of tumplines. It is likely that, in addition to migrating from her homeland, she spent much of her life transporting heavy loads in the rural Nile environment — perhaps even carrying children from her family or community. A way of life as common as it is overlooked by written history.

"This way of life is as common as it is overlooked by written history", explains Jared Carballo. "In some way, the study reveals how women literally have carried the weight of society on their heads for millennia."

This study supports a growing perspective that sees the human body as a biological archive of lived experiences. In this sense, bone modifications are not simply the result of ageing; they also reflect social patterns, such as the division of labour and gender roles. Therefore, anthropological concepts like "body techniques" (ways in which people use their bodies in different societies in everyday activities such as walking, running, or using tools) or "gender performativity" (differences in movements dues to imitation or social conventions) offer a framework for interpreting how repeated tasks shape bones and configure bodies according to identity.

Such practices, also observed in representations of Nubian women in later Egyptian tombs and still documented today in rural communities across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, have long been invisible in historical narratives. However, as this research shows, their impact was so profound that they literally reshaped the anatomy of those who performed them. Head-loading was not only a physical effort but also a material expression of inequality and resilience.

As a result, the study opens new avenues of research into women's mobility, the physical implications of motherhood, and the economic and logistical roles of women in rural societies. "Abu Fatima thus offers a new window into the deep past of the fascinating Nile Valley and a powerful reminder of how heavy the silences around women in history still are", Jared Carballo concludes.

The research included the participation of archaeologists from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Leiden University, the University of Essen, and the University of California Santa Barbara.

Article reference:

Carballo-Pérez, J., Matić, U., Hall, R., Smith, S.T., Schrader, S.A. (2025). Tumplines, baskets, and heavy burden? Interdisciplinary approach to load carrying in Bronze Age Abu Fatima, Sudan. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 77: 101652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2024.101652