The cannabis-derived product CBD has been hailed "the wonder drug of our age" , offering potential health benefits without the high. From juices and coffee to truffles and ice cream, CBD products have flooded the market for consumers looking for an answer to health problems from anxiety to insomnia.

Author

- Lauren Alex O'Hagan

Research Fellow, School of Languages and Applied Linguistics, The Open University

But with CBD products in the UK and EU falling under "novel foods" regulations rather than pharmaceutical standards, they aren't subjected to the same rigorous safety and quality controls as drugs. The UK's Committee on Toxicology has even flagged potential health risks, such as liver injury , leading the Food Standards Agency to issue safety guidance .

The regulatory gaps and health concerns of today reflect those of the 19th century when cannabis products were commercialised by the food industry.

In the 1830s, William Brooke O'Shaughnessy , an Irish doctor, discovered that cannabis was effective in treating muscle spasms and stomach cramps. French psychiatrist Jacques-Joseph Moreau later explored its potential for mental illness. This led many 19th-century doctors to champion cannabis as a cure-all.

It wasn't long before patent medicine manufacturers began using cannabis as a common ingredient in their formulas. But soon, cannabis wasn't just in pharmacies - it was in food.

Surprisingly, this shift was not driven by the food industry, but by the free church environment in Sweden as part of efforts to combat tuberculosis - a leading cause of death across all social classes in the country at the time .

Paul Petter Waldenström, leader of the Swedish Mission Covenant, wrote a letter to Svenska Morgonbladet about a woman reportedly cured of tuberculosis by a homebrewed gruel made with hempseed, rye flour and milk. His endorsement helped popularise the remedy and many started making their own "Waldenström gruel" , as it became known.

Sensing a business opportunity, entrepreneur J. Barthelson developed a powdered commercial version with the elegant French name Extrait Cannabis. He marketed it as a dietary remedy for tuberculosis, chest diseases and low energy. As demand grew, competitors quickly jumped on the bandwagon, using fearmongering tactics to persuade consumers that they were putting their lives at risk without it.

The rise and fall of Maltos-Cannabis

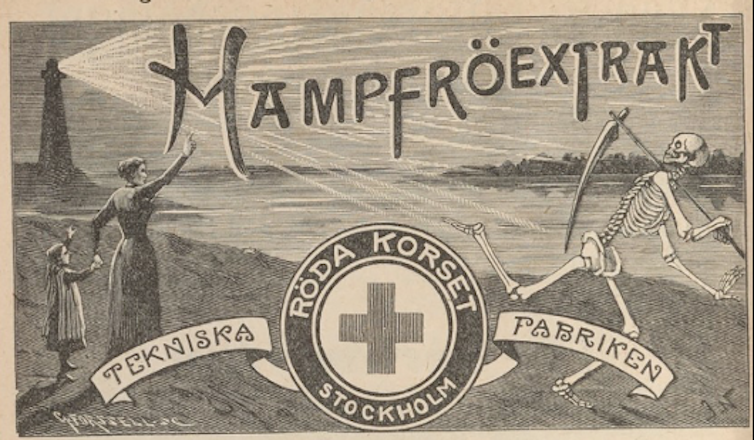

The most striking cannabis-infused product of the era came from the Red Cross Technical Factory. Their "health drink", Maltos-Cannabis, was a maltose and cannabis blend marketed as both nutritious and delicious, especially when mixed with cocoa.

With an aggressive advertising campaign, the company raked in nearly SEK 290,000 a year (around £775,000 in modern money), opening factories in Chicago, Helsinki, Brussels and Utrecht.

A particularly dramatic advertisement depicted the Grim Reaper fleeing from the light of science, shining from a lighthouse. Meanwhile, a mother and daughter raised their arms triumphantly, symbolising victory over death thanks to Maltos-Cannabis. The tagline boldly claimed that the product had "a big future".

However, questions swirled about its legitimacy. Newspapers debated whether the product was a groundbreaking remedy or "a pure scam product" . While some critics called the craze an "epidemic", others argued coffee was more harmful - a hot topic in Sweden's parliament at the time.

In response, Red Cross published a half-page rebuttal signed by its executives, defending the product's credibility. But scepticism persisted. After various lawsuits and growing concerns over its effectiveness and safety, sales of Maltos-Cannabis began to decline. By the 1930s, the product had disappeared entirely.

History repeats itself?

The 19th-century commercial cannabis market was able to thrive due to the absence of marketing regulations for both food and pharmaceutical products. Manufacturers freely advertised their products using pseudo-scientific claims and buzzword-heavy marketing - strategies we're seeing again today in the thriving CBD industry.

This is because CBD is a "borderline" product, existing in a regulatory grey area that allows for marketing strategies to flourish without stringent oversight. Much like in the past, brands tap into consumers' health anxieties with promises of a wellness revolution. Most worryingly, social media influencers are being used to endorse CBD, making it particularly appealing for younger audiences.

With the global CBD market valued at US$19 billion in 2023 and projected to grow by 16% annually until 2030, looking back at the broader, problematic history of commercial cannabis should serve as a cautionary tale.

![]()

Lauren Alex O'Hagan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.