It started with a hacksaw and a multimillion-dollar instrument. Richard Caprioli, then a postdoctoral fellow, was given the hacksaw to cut the instrument in half during his first day in the lab of John Beynon, professor of chemistry at Purdue University and author of one of the earliest books on mass spectrometry. Caprioli installed a new detector in the cut-open instrument and developed a yearning to "do innovative things with instruments," particularly with mass spectrometry. This yearning has accompanied Caprioli throughout his career and has resulted in him becoming a pioneer of new mass spec techniques, such as imaging mass spec.

Caprioli, now the Stanford Moore Professor of Biochemistry at the School of Medicine Basic Sciences, didn't have a genuine science bent growing up, although he and his brothers had the notion of one day opening a pharmacy. After completing high school in his native Deer Park, New York, Caprioli got a fellowship from the National Science Foundation to do undergraduate research at the Columbia University College of Pharmacy.

Caprioli worked for a professor who was looking at different types of penicillin to figure out how to change its structure to make it just as effective but not have side effects. As an undergrad, Caprioli synthesized three or four new penicillins, including one that was extremely active-more so than the normal penicillin G, benzylpenicillin. "Sadly, it had really negative side effects, so it never got anywhere," Caprioli said. "But that was my exposure to real science and molecular science, and I loved creating something and then seeing if it would have a positive health effect." At Columbia, Caprioli caught the bug for using his hands to create something.

Medical school briefly beckoned before Caprioli focused his attention on basic science. In 1965 he was accepted into Columbia's Ph.D. program under the guidance of David Rittenberg of the Department of Biochemistry. Rittenberg pioneered the isotopic tagging of molecules and was a "fantastic mentor" who Caprioli credits for his own desire to teach and train students. "It came from him, there's no doubt," Caprioli said. "He would have said, 'If you want to label me a researcher or this or that, okay, but the one word I want is teacher.' That resonated with me."

Breaking eggs to make omelets-and better instruments

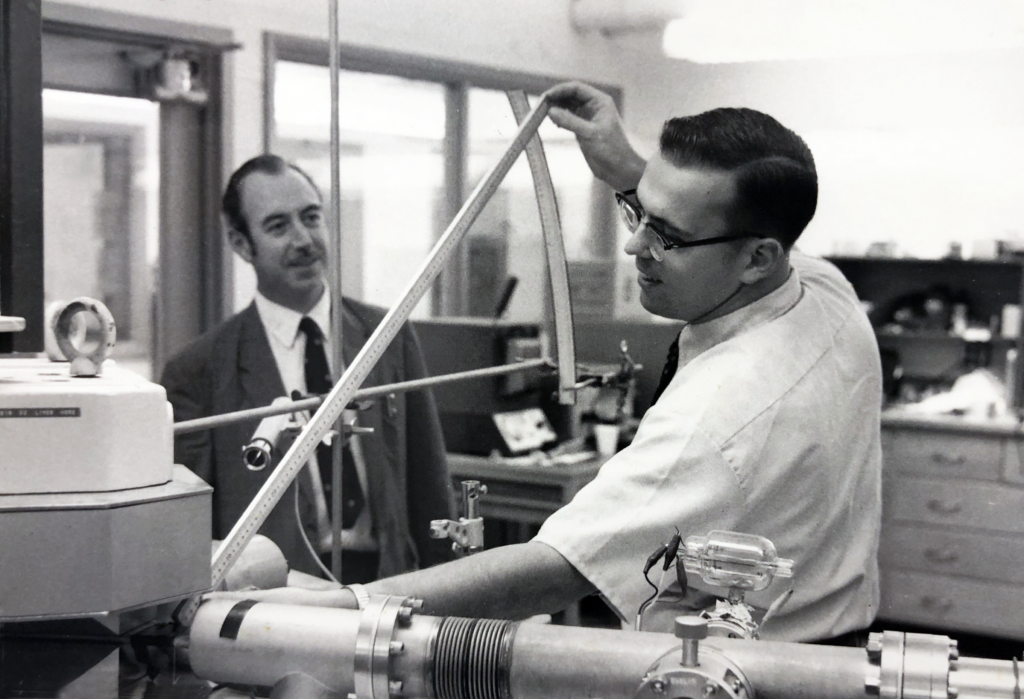

Caprioli's first experience with a mass spectrometer occurred in the Rittenberg lab. A mass spectrometer measures the mass-to-charge ratio of an ionized molecule, allowing its exact molecular weight to be calculated. Mass spectrometers are used to identify unknown compounds, to quantify known molecular compounds and to determine the structure and chemical properties of molecules. The instrument he used was an old-fashioned isotope ratio mass spectrometer made of glass that had a boiling mercury pump. "Every day I had to put dry ice and alcohol or acetone in this thing and hope that none of the boiling mercury got out," he said. But he was convinced that there was a larger role for mass spec in biology and biochemistry than was being explored solely through isotope ratio mass spec, so he applied for a postdoctoral position at Purdue with Beynon, a Welsh chemist and physicist known for his work in mass spec.

That's where the hacksaw story comes in. Caprioli produced a lot of papers thanks to the modified instrument, which allowed for "a whole new way of using a mass spectrometer" than was previously possible. Better yet, it taught Caprioli a valuable lesson: new equipment, even expensive equipment, could be modified.

Expertise pays off

One fateful day, Rittenberg and a redheaded stranger wearing boots, jeans, and a cowboy hat approached Caprioli. The cowboy, the renowned James "Red" Duke, best known for being the first surgeon to attend to President John F. Kennedy after he was shot in Dallas in 1963, was there to learn everything Caprioli could teach him about mass spec.

Several years later, Caprioli, by then an assistant professor of chemistry at Purdue, got a call from Duke inviting him to become part of a new medical school in Houston. "I don't want to go to Texas," Caprioli said to Duke, who offered to host him for a lecture and scientific discussions instead. Despite his initial reservations, Caprioli accepted an offer once he was on site and remained at the University of Texas Medical Center for twenty years, teaching biochemistry to medical students, running a research program, and serving as director of the mass spec-based analytical center

Vanderbilt beckons

In 1998, Larry Marnett, University Distinguished Professor and dean emeritus of Basic Sciences, led the search for a new director of the School of Medicine mass spec facility. One of the sources Marnett relied on was Bob Murphy, a distinguished mass spectrometrist, who recommended Caprioli as someone he should contact. By that time Caprioli had already made his mark on the field with micro-electrospray mass spec.

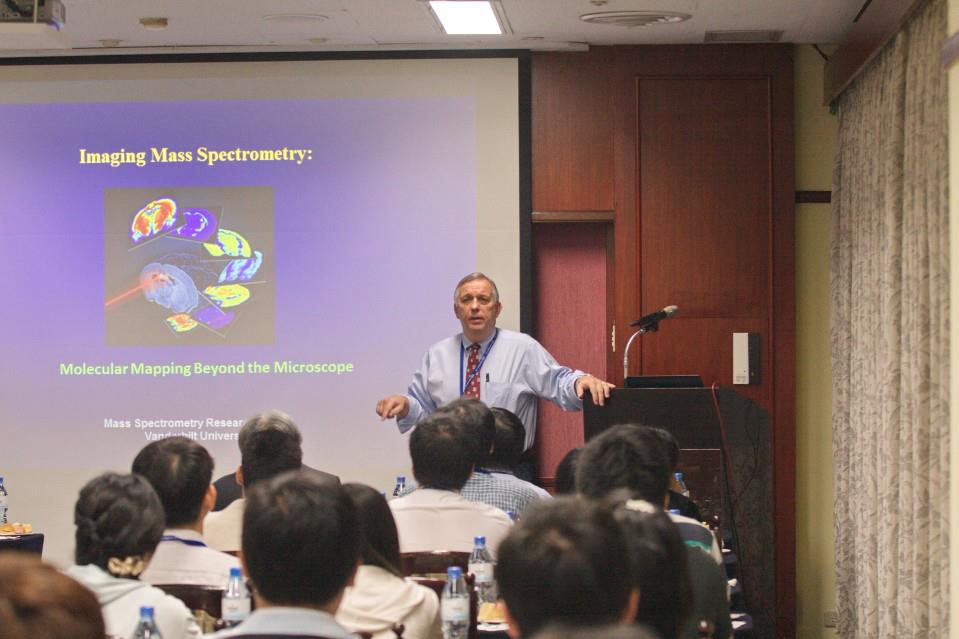

"Richard was doing cutting-edge research and had experience running a medical center-wide core facility," Marnett said. "He not only brought a capability for protein mass spectrometry that we didn't have, but he also introduced us to imaging mass spectrometry." Imaging mass spec retains information about where the molecules are located within thinly sliced tissue samples. At the time, imaging mass spec was just in its infancy and was poised to transform biological mass spec.

"I liked Texas, but when I interviewed at Vanderbilt, I could see a much more dynamic place, and I could see a better interaction with clinicians," Caprioli said. "I liked the collegiality that I saw here."

Crafting a place of excellence

Over the years, mass spec has been used to help diagnose genetic diseases in newborns, detect the use of steroids in athletes, monitor patients' breathing during surgery, locate oil deposits by measuring petroleum content in rocks and more.

"Richard has innovated multiple technologies, and his impact on the field of mass spectrometry has been enormous," Kevin Schey, Stevenson Professor of Biochemistry, said. Schey is also the deputy director of the Mass Spectrometry Research Center, which Caprioli leads.

Caprioli's work has created new possibilities for understanding the relationships between molecular and cellular organization in tissue microenvironments, ultimately providing a precision medicine toolbox for uncovering the molecular underpinnings of normal aging and disease.

Caprioli is best known for developing matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization imaging mass spec, for which he received the John B. Fenn Distinguished Contribution in Mass Spectrometry Award from the American Society for Mass Spectrometry in 2014. MALDI imaging mass spec allows proteins, lipids, metabolites, and drugs to be localized in tissues with near single-cell resolution. This technology has had a major impact on biomedical research by providing scientists with the ability to determine spatially resolved molecular compositions in tissues in a variety of disease settings or within the context of different drug treatments. The pharmaceutical industry has adopted this technology to track drugs and their metabolites within tissues and to clarify mechanisms of toxicity.

In 2015 Caprioli's group achieved the first fusion of mass spec and microscopy, allowing scientists to see the molecular make-up of tissues in high resolution, an advance that could drastically improve the diagnosis and treatment of cancer.

Caprioli and his staff have transformed Vanderbilt's MSRC into a world-class facility that houses dozens of state-of-the-art instruments and consistently recruits the brightest minds in the field. The MSRC provides mass spec services in proteomics, small molecule (drugs, metabolites, lipids) mass spec, and imaging mass spec to the Vanderbilt community. It also attracts scientists from around the globe who attend annual lectures and workshops to learn the workings of MALDI imaging mass spec.

The center has supported many individual federal grants as well as large center grants, including from the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center, the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Center, and the Vanderbilt Vision Research Center. In 2023 Bruker Daltonics-a manufacturer of scientific instruments for molecular and materials research, including mass spectrometers-established a strategic partnership with Vanderbilt by creating a Mass Spectrometry Center of Excellence, the first of its kind, housed within the MSRC.

"Through vision and leadership of the MSRC, Richard has led the way in developing imaging mass spectrometry, continually pushing the boundaries of what is possible to enable molecular imaging at cellular resolution," said Jeffrey Spraggins, associate professor of cell and developmental biology and member of the MSRC.

A culture of innovation

Passing on his knowledge to the next generation of scientists is a passion of Caprioli's. "I've always told my students that I don't give Ph.D.'s-they earn them," he said. Caprioli's mentoring philosophy involves letting his students decide on their own experiments, even when he doesn't think they will work. "When something works, a student might think, 'I understand it.' No, you don't-you were lucky. But things that don't work, you go back and do an autopsy on them. You learn all kinds of things."

His mentoring style appears to be working as his students usually have jobs waiting for them as soon as they graduate. The fact that every medium to large pharmaceutical company has an imaging mass spec laboratory-based on Caprioli innovations-also helps.

From hacksaw to band saw

Besides mass spectrometry and fast cars-Caprioli has driven a Ferrari since before coming to Vanderbilt-woodworking holds a special place in his heart. Five years ago, Caprioli built a 4,000-square-foot cabin atop a mountain surrounded by 30 acres of land in the Smoky Mountains. There, after retiring from Vanderbilt in August 2024, he will apply the same inventive mindset he brings to science in his woodworking shop.

"Innovation is the commonality with science and woodworking," he said. "You can make things that don't exist; they come out of your mind. It's innovation."

It's the Caprioli way.