Overview

In 2023, four Chinese nationals were charged with violating the International Emergency Economic Power Act (IEEPA) and the Iranian Transactions and Sanctions Regulations (ITSR) due to their involvement in an illicit scheme to procure dual-use items from U.S. companies for Iranian end users. The defendants, Baoxia Liu, Yiu Wa Yung, Yongxin Li, and Yanlai Zhong, for whom arrest warrants have been issued, remain fugitives. They are accused of being involved in a decade-long scheme in which a variety of Chinese front companies were utilized to acquire dual-use items from U.S. companies for the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), a branch of the Iranian Armed Forces, and the Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistic (MODAFL), Iran's defense ministry charged with the development and production of military weapons, such as ballistic missiles and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV). [1] Both the IRGC and MODAFL, along with their related entities, are listed on the Office of Foreign Assets Control's (OFAC) Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) and Blocked Persons list due to their involvement in weapons of mass destruction (WMD) proliferation. The U.S. companies from which the defendants acquired the dual-use items were distributors and manufacturers of a wide variety of products, from electronic equipment and telecommunications products to semiconductors.

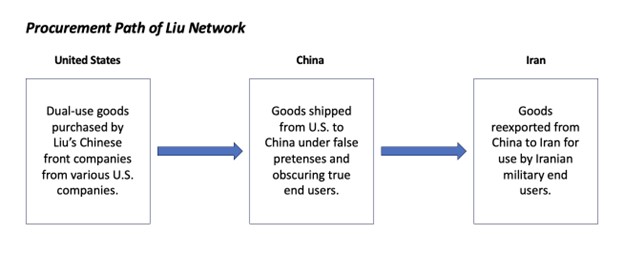

The defendants' illicit procurement activities involved actively deceiving U.S. companies as to the end users of the goods, unlawfully exporting the U.S. products to Iranian entities, as well as falsifying export documentation, obfuscating the true end user of the goods.

Legal Background of Charges

These charges stem from violations of regulations under the International Emergency Economic Power Act (IEEPA) and export/shipping regulations. Under the IEEPA and Executive Orders 12957, 12959, and 13059, a comprehensive trade and financial embargo was imposed on Iran. To implement the Executive Orders, the Iranian Transactions and Sanctions Regulations (ITSR) was created by OFAC, and prohibits "the export, reexport, sale, or supply, directly or indirectly, of any goods, technology, or services from the United States … to Iran." [2] Additionally, under export and shipping regulations, exporters are required to file Electronic Export Information (EEI), which includes information regarding the end user of the goods being exported as well as its ultimate destination. By falsifying EEI documents, obscuring the true destination of the dual-use goods, and by reexporting the goods from China to Iran, the defendants violated these U.S. regulations.

The Scheme

From May 2007 until at least July 2020, the group of defendants, led by Baoxia Liu, was involved in an illicit procurement scheme designed to funnel dual-use goods of U.S. origin to Iran for use in its ballistic missile and drone programs. [3] The scheme involved several China-based front companies, which were used interchangeably in Liu's procurement network. [4] Liu and her associates presented themselves as representatives of multiple Chinese entities, including Abascience Tech Company LTD, which was "advertised as a professional supplier of electronic components", Sunway Tech Co. LTD, which "claimed to be engaged in the sales of electronic devices, communication equipment … and other such products", Sunray Global Technology Company Limited, a "PRC-based global technology company registered in Hong Kong", as well as Raybeam Optronics Co., another "PRC-based corporation that claimed to specialize … in infrared thermal imaging products." [5] Two of these companies, Sunray Global Technology Company Limited and Raybeam Optronics Co., shared an Iranian director who simultaneously served as the Chairman of the Board of Rayan Roshd Afzar, an Iranian technology company which has been on the OFAC's SDN list since 2017. [6] Additionally, Abascience Tech Company has been on the SDN list since 2017. [7] A search for these companies, including variations of their names, in global trade databases yields no results. This might be partly because the database doesn't cover all of the years since the scheme began in 2007. However, the absence of data also highlights the possibility that once companies are identified and sanctioned, they can disappear and operate under different aliases or names.

These Chinese front companies facilitated the purchase of dual-use goods from 15 unnamed companies in the U.S. The items procured included "digital integrated circuits, a multi-filament winder, keypad interfaces, voltage suppressors, digital compasses, field effect transistors, resistors, dowel pins, military standard fasteners, heat shrink boots, circular connectors, flanges, toggle switches, a fixed ratio DC-DC converter and a non-isolated regulator." [8] Throughout the decade-long operation, the defendants never obtained the required export approval licenses from OFAC for these transactions. Additionally, the defendants intentionally concealed that the ultimate end users of the goods were Iranian entities, leading to the shipment of goods to China under false pretenses.

The true Iranian end users were sanctioned companies associated with the IRGC and MODAFL. One of the end users, Shiraz Electronics Industries, advertised itself as "an appliance, electrical and electronics manufacturing company headquartered in Iran that produced radar and electronic equipment for the Iranian military, repaired Iranian military equipment and worked on products for Iran's avionics, naval radar and ballistic missile programs", but was owned and controlled by MODAFL. Shiraz Electronics Industries is sanctioned by the United States and European Union. [9] According to the E.U. sanctions listing, the company is associated with Iran's proliferation sensitive nuclear activities and development of nuclear weapon delivery systems. The other company, Rayan Roshd Afzar, was "a technology company with ties to the IRGC and MODAFL that was headquartered in Iran" that "produced technical components for Iran's UAV program, sought to repair Iranian military equipment and worked to produce software for the Iranian aerospace program." [10] The company was sanctioned by the United States on July 18, 2017, for providing material support to the IRGC. [11]

Figure 1. Figure illustrating procurement path of goods in Liu's illicit procurement network.

Lessons and Recommendations

Despite the implementation of federal export control laws to prevent WMD proliferation and the export of dual-use goods to Iran, Iranian related entities are still able to acquire these dual-use products and use them for military purposes via third countries, such as China. This case highlights how Iran is dependent upon complex illicit procurement schemes to acquire advanced Western dual-use materials it cannot produce domestically for its ballistic missile and drone programs. Although this case and many others have made transparent the extensive assistance to Iran' weapon programs by Chinese nationals and front companies based in China, the United States and its allies should continue prioritizing calling on China to enforce its national laws and crack down on illicit actors and front companies operating within its borders and its economy.

The long-standing nature of this illegal procurement effort highlights the ongoing need of the U.S. government to communicate with companies in industries which design and manufacture dual-use goods, informing them about the potential military uses of their products and the strategies which traffickers use to subvert U.S. controls. As traffickers intensify efforts to obtain sensitive dual-use goods and technology, in some cases trying to obtain the means to make the item themselves, the Disruptive Technology Strike Force (DTSF), formed in 2023, is a welcome development. The DTSF is a strike force consisting of several federal agencies such as the Department of Justice, Department of Commerce, Homeland Security, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Defense Criminal Investigative Service; it aims to prevent foreign states from illicitly acquiring U.S. sensitive technology. Its efforts to reach out to companies should be encouraged, particularly its efforts to identify the types of illicit procurement it is encountering.

The misuse of the Electronic Export Information system points out its dependence on honest exporters and the ease of falsely declaring the end user. One component that can be fixed is the requirement that exporters file accurate information in the EEI declaration about the end user, including its address. Often, exporters list shipping or logistics companies or trading companies, which are clearly not the end users. The U.S. government should police the declarations as they are being submitted electronically, perhaps using AI, and reject any declarations with obviously false end users.

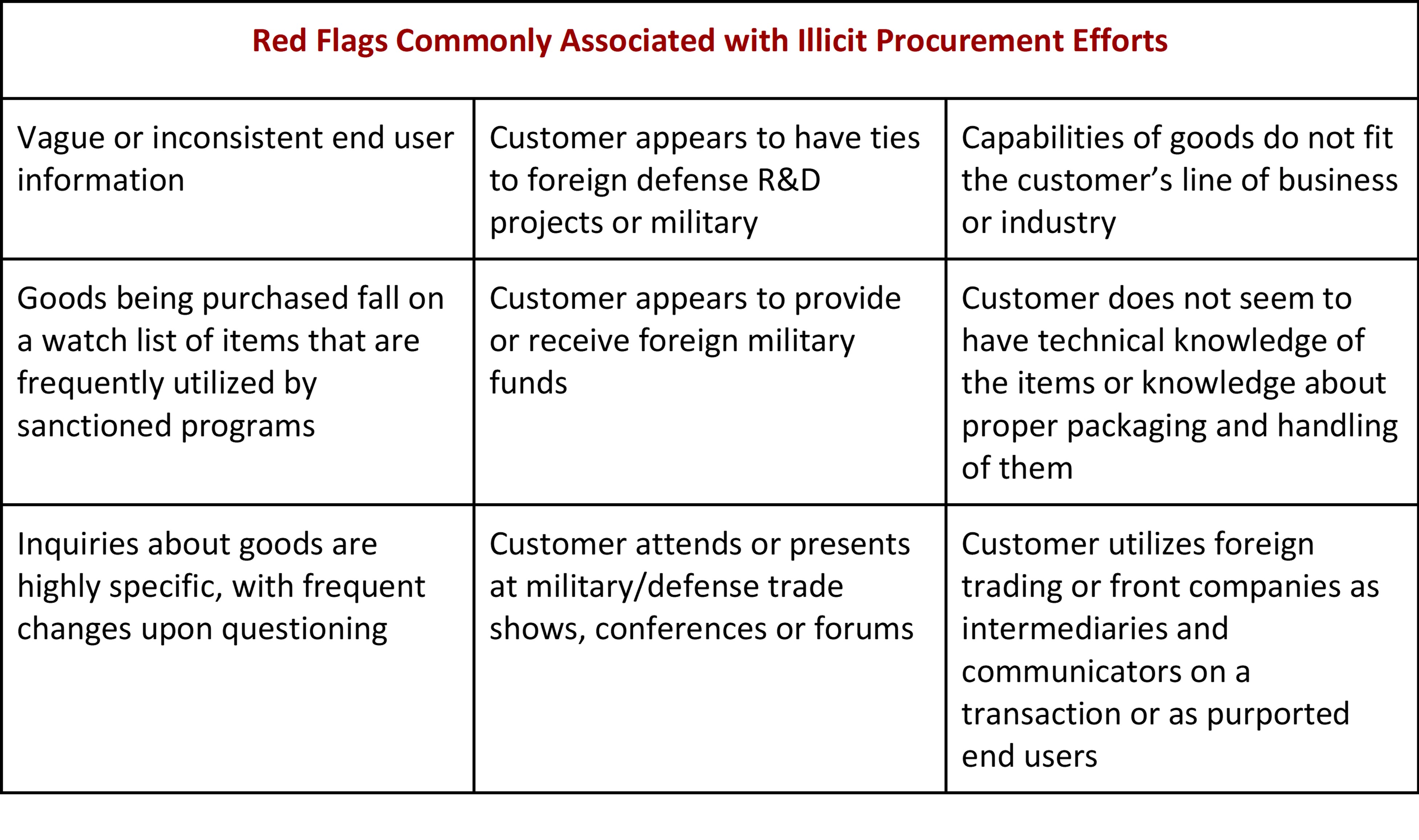

While government regulations, enforcement, and outreach are critical, ultimately, private U.S. companies need to do a better job detecting illicit trade. They are the first line of defense and have an obligation to conduct proper due diligence on their customers and potential end users. This involves verifying the identities and backgrounds of customers, understanding the intended use of purchased goods, and monitoring for any suspicious activities or inconsistencies. Additionally, companies should be not only aware of a list of red flags that indicate potential evasions of export controls and sanctions but also actively adding to this list (see Table 1). By identifying and acting on these red flags, companies can help mitigate the risk of illicit procurement efforts, such as the scheme conducted by Liu and her associates.

Western manufacturers should be wary of selling dual-use goods to obscure or little-known companies. Unknown new customers seeking dual-use goods should be properly audited by Western manufacturers to verify their identity and potential end use. Proper due diligence can include looking into company websites, verifying company addresses, looking for beneficial ownership information on companies (if any is available), researching whether the company has a track record of legitimate business (can be assessed by looking at import-export trade manifest data or communicating with other business partners and government officials), and verifying the identity of procurement agents and company staff members. Several of the companies involved in this illicit procurement scheme had little to no online presence, a clear red flag for any Western manufacturer to watch for. If customers refuse to cooperate and apply adequate end-use control, companies should terminate their contracts and report the matter to authorities.

Companies in key industries should ban the sale of the most sensitive and sought after dual-use goods to Chinese companies. As an additional precaution, Western companies should invest in moving supply chains and manufacturing centers out of China to prevent any unauthorized transfer of sensitive dual-use commodities, especially those associated with Harmonized System (HS) Codes found on the Bureau of Industry and Security Common High Priority List (CHPL). [12]

Table 1. Red flags and warning signs identified in the illicit procurement scheme. [13]

1. "Chinese Nationals Charged With Illegally Exporting U.S.-Origin Electronic Components to Iran and Iranian Military Affiliates," U.S. Attorney's Office, District of Columbia, January 31, 2024.https://www.justice.gov/usao-dc/pr/chinese-nationals-charged-illegally-exporting-us-origin-electronic-components-iran-and.[↩]

2. United States v. Liu (United States District Court for the District of Columbia September 15, 2023), 10. [↩]

3. "Emily Liu," Iran Watch. https://www.iranwatch.org/suppliers/emily-liu. [↩]

4. United States v. Liu, 6. [↩]

5. ld. at 5. [↩]

6. Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List. https://sanctionssearch.ofac.treas.gov/Details.aspx?id=22688. [↩]

7. Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List. https://sanctionssearch.ofac.treas.gov/Details.aspx?id=22684. [↩]

8. "Emily Liu". [↩]

9. Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 503/2011. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:136:0026:0044:EN:PDF. [↩]

10. United States v. Liu, 3. [↩]

11. John E. Smith, "Notice of OFAC Sanctions Actions," Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/07/21/2017-15364/notice-of-ofac-sanctions-actions. [↩]

12. "Common High Priority List," Russia Export Controls - List of Common High-Priority Items. https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/all-articles/13-policy-guidance/country-guidance/2172-russia-export-controls-list-of-common-high-priority-items. [↩]

13. For a more detailed list, see David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, Spencer Faragasso, Linda Keenan, and Andrea Stricker, Illicit Trade Networks - Connecting the Dots, Volume 1 (Washington, DC, Institute for Science and International Press, 2020), available at https://isis-online.org/books/detail/illicit-trade-networks-connecting-the-dots-volume-1. [↩]