The sheer size of the Great Barrier Reef is difficult to grasp. In an area larger than New Zealand, the entire marine park spans almost 350,000km2 and is made up of 3,000 individuals reefs. One of the central questions in Reef conservation efforts is how and where to use the limited resources we have for maximum impact. For this reason, modern scientists are often called upon to see into the future using data.

Dr Catherine Kim, lecturer and marine scientist with the Queensland University of Technology, knows the difficulties of predicting the future well. Her research into coral rubble - dead coral skeletons and rock fragments that collect on the reef floor - uses spatial data and modelling to anticipate which of the 3,000 reefs are most likely to have high levels to coral rubble. While coral rubble is a natural and important habitat on reefs, too much rubble, caused by cyclones and bleaching events, can damage newly settled corals and prevent reefs from recovering.

"If we can accurately predict which reefs will have too much rubble, then we can efficiently manage and apply solutions to stabilise rubble and restore coral reefs," Catherine says.

"Assessing such a large ecosystem is very complex and makes it very difficult to monitor and manage, especially in a changing future. Imagine trying to predict what 3,000 people are going to be doing in 10 years' time - it would depend a lot on circumstances surrounding each individual: age, background, culture, health.

"We know that because of climate change, the future outlook of the Reef is not great, but figuring out how we should best manage, protect and help the Reef is a complex problem that a lot of researchers are trying to address."

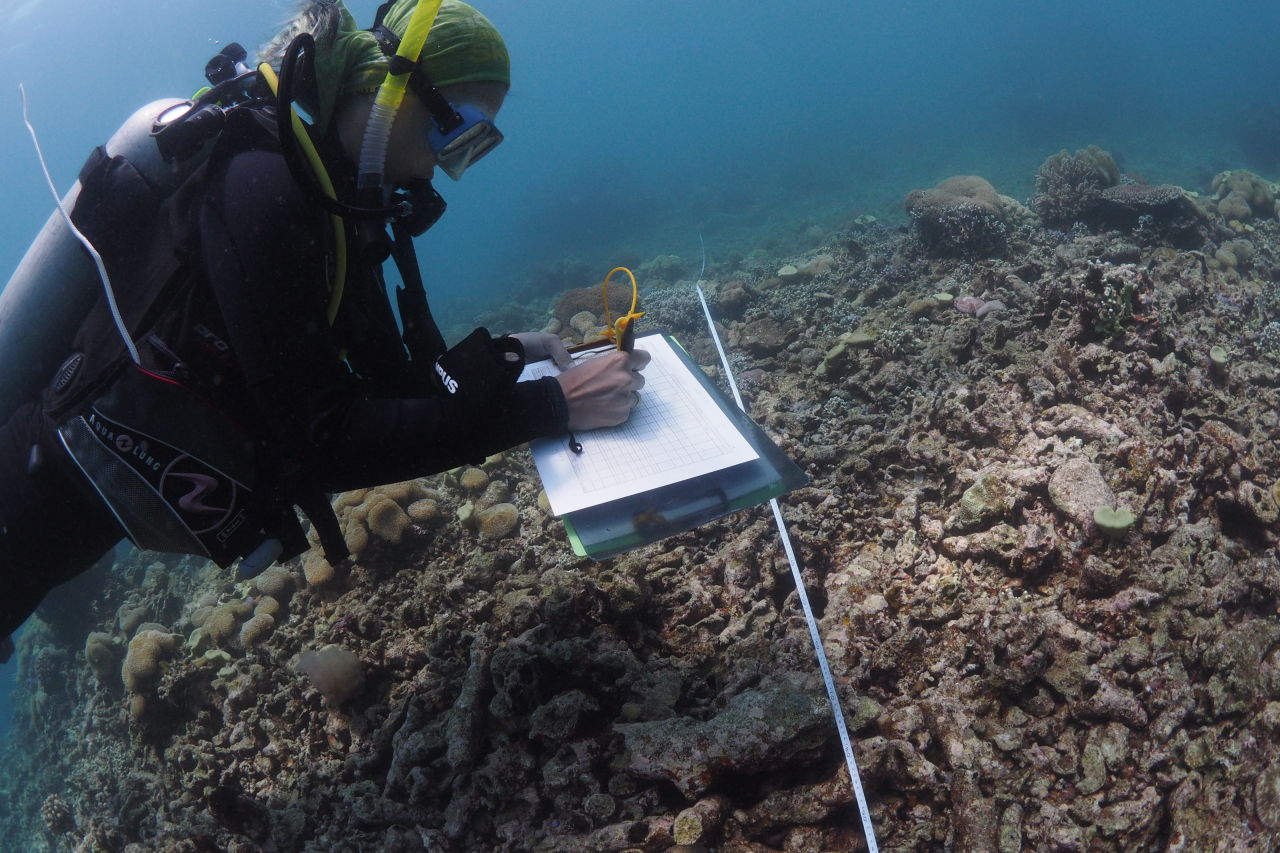

Catherine Kim conducting coral surveys in Timor Leste. Credit: Shakib Haron.

Catherine was recently recognised in the 2023 Queensland Women in STEM Prize and she is part of the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program's Rubble Stabilisation subprogram. Her research uses statistical models and machine learning to assist in maintaining the health of the Great Barrier Reef.

To conduct this work, Catherine needs to draw on a vast and unique skillset in the lab and the field. She admits she has learned to enjoy coding, which is critical for modelling.

"There was a big learning curve trying to do analysis for my PhD, but it's about breaking down a problem into smaller steps which can be very rewarding."

Catherine was recently recognised in the 2023 Queensland Women in STEM Prize.

Catherine says her greatest professional achievement to date is her PhD reef research in Timor-Leste.

"I learned that the context surrounding reefs is very important. The history, language, and culture all influence the environment. My ability to conduct research in Timor-Leste and present to the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries and the National University was very rewarding. The coolest discovery I made during my PhD was that the Indonesian Throughflow surrounding Timor Island significantly cools shallow reefs during the austral summer," Catherine says.

"I'm motivated by the sense of discovery that comes with oceans and reefs, by continuous learning, and by having a positive impact so everyone in the future can also experience the wonders of the ocean.

"The fact that we get to experience this truly amazing ecosystem in our lifetimes is special. It was not until I visited the Great Barrier Reef myself that I realised how remote it is. Even for Australians, it can be a trek to get to."