When the Writing Seminars faculty reviewed Chris Childers' application for the MFA in creative writing, they shared what professor Mary Jo Salter remembers as "unanimous amazement." Occasionally, applicants already have poems in literary journals or even books under their belt, but Childers had something rare, if not totally singular: a contract with Penguin to translate a volume of Greek and Latin lyric poetry, a project requiring the translation of more than 80 poets from across eight centuries in two ancient languages.

Image caption: Chris Childers

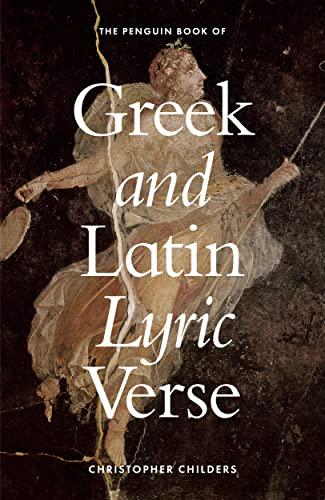

That was 2014; now, 10 years later, Childers' book, The Penguin Book of Greek and Latin Lyric Verse, has finally come into print (in the UK, at least; the U.S. edition will drop in 2025). To call it a collection of poetry would be to diminish it, for included in its 956 pages are a guide to Greek and Latin poetic meters, a note on the definition of lyric poetry, short biographies of every poet included, introductions to every time period covered in the book's 800-plus year span, an afterword by classicist Glenn T. Most, and, of course, lots of poetry. In her exultant review of the book for The Telegraph, poet and translator A.E. Stallings said the volume "practically amounts to a degree in classical literature in translation."

In the book's preface, Childers describes those 10 years as an "epic undertaking," or "a sort of personal odyssey." If his journey was less perilous than Odysseus', it was certainly no less arduous.

One might guess this project would require lifelong familiarity with the Latin and Greek languages, but Childers did not encounter either one until his undergraduate years at UNC Chapel Hill. He didn't make the decision to study classics until he met English professor Robert Kirkpatrick at summer orientation.

"I started studying the classics because … [he] told me, if you really want to learn to write well, you should study Latin or Greek," Childers says. "And I was just so impressed with him. He was a towering figure, a very large man with a soft and beautiful voice, and he just seemed to know everything. And I immediately understood I could learn a lot from him. So I started Latin my first year at UNC, and then I took up Greek my second year."

He started translating in a creative writing class during his sophomore year, where he recalls "making a botch" of Virgil's fourth eclogue. But everyone has to start somewhere, and that same eclogue appears in his book: "Sicilian Muses," it begins, "let's make a grander poem."

So he did, by the hundreds. After graduation, Childers was teaching at a boarding school when he contacted an editor at Penguin in hopes of translating either the Aeneid or Pindar. The editor turned down both proposals and offered up his own: Why not tackle the entirety of Greek and Latin lyric verse?

Despite feeling daunted by the project, Childers agreed to it, imagining a four- to five-year timeline. But building the table of contents alone took a year of reading and selecting candidates for translation. And then, of course, came the actual act of translation, a task Childers enjoyed but found required patience, especially since teaching made free time scarce. He translated when he could, comparing the effort—slow but steady—to swimming: "In 2018 I spent two weeks in Greece, in a town called Selianitika on the Gulf of Corinth. Every morning, I would go out before dawn and take a long swim towards this Ferris wheel on a headland jutting out way off in the distance, and it would take 40 minutes to swim there and 40 more to swim back. And while I swam, I thought about making the same kind of progress towards the end of the book. One stroke after the next. Every day, just a few more lines."

To make more time for the project, Childers applied to study poetry in the Writing Seminars' two-year MFA program and was one of four poets chosen for the Class of 2016. Each semester, MFA candidates take two graduate seminars and teach one section of Intro to Fiction and Poetry or work on The Hopkins Review, leaving them with ample time to write. Childers wrote original poetry for his thesis on top of his translation project, joining a long tradition of poets translating other poets, a group that includes Seamus Heaney, Richard Wilbur, and Ezra Pound—to name just a few. The allure of translation for poets might be that it's the ultimate word puzzle. Some of us play crosswords; others labor over how to bring to life Ancient Greek poetry—its context, culture, rhythm, humor, and feeling—in another language.

Poetry professor David Yezzi explains, "The challenge for the translator, and it's a daunting one, is to create a musical poem in English. In other words, a poem that has all the emotional power and expressiveness of the original, as close as you can get to it, and as much as you can suggest it using an entirely different language."

Possessing a knack for writing original poetry certainly helps. Yezzi says, "[Childers'] original poems, like his translations, are quite fluent, quite musical. Chris has one of the best ears of any younger poet I can think of, and his translations really benefit from that."

Childers says he received feedback on his translations from professor emerita Mary Jo Salter and James Arthur, associate professor and director of graduate studies for the Writing Seminars, but neither of them would take full credit.

Arthur says, "I don't have any real reading knowledge of Greek or Latin myself, so I thought, what kind of advice can I offer here? I said to Chris, 'Look, I can't really comment on the quality or the fidelity of the translation, but I can talk about it in poetic terms and look at the rhetorical and rhythmical effectiveness of the translation as presented.' And that's what we did, and I enjoyed it."

Salter recalls Childers asking her to help decide which poems to leave out of the book: "He gave me a big sheath of Greek epigrams and said, 'The main thing I want you to help me with is to figure out which of these aren't good enough to include.' And I kept saying, 'I'm sorry, I'm trying my best, I'm trying to find something that I don't like, but I'm really finding this difficult.'"

In a talk earlier this year with Department of Classics chair Karen ní Mheallaigh, Childers compared the act of translation to acting as a medium. The poets speak, but through the distinctive voice of a 21st century American poet. The resulting translations feel timeless. The bawdy verses of Catullus, rife with profanity, brutal excoriations of ex-lovers, and lighthearted mocking of friends ("How's that? You're pale; your hygiene's sliding / from late nights in the saddle, riding"), aren't so far removed from today's diss track wordplay. One could imagine Sappho's expressive fragments ("Love's got me again, that impossible / limb-loosening, bittersweet animal") racking up reposts on Tumblr. It's easy to forget you're reading ancient poetry until a deity is invoked, such as in the beginning of Propertius 2.28: "My sweetheart's sick: Jupiter, show some pity! / Keep death off your hands—she's far too pretty!" Childers isn't afraid to place contemporary idioms alongside gods and goddesses, a reminder that the spectrum of emotion on display in Greek and Latin lyric verse, its heartbreak and anger and joy, is our own.

The narrative arc of this book is the evolution of a poetic tradition. Read cover to cover, the book's many parts converge into a portrait of two ancient civilizations bound by the craft of lyricism, the Italians learning and borrowing from the Greeks. Despite the clear link between the two, Latin and Greek lyric verse are typically packaged separately, rather than as one continuous movement. By bringing them together in one volume, Childers invites readers to consider Latin poetry's roots in Greek translation.

"When you're reading Latin," he says, "you're always aware of their Greek models and that they're using Greek meters. Horace [an Italian poet who wrote in Latin] boasts at one point that his greatest achievement is that he was first to have brought over Aeolian song into Italian measures. And so the Greekness of the meter, form, and style is essential to what Latin poetry is all about."

If Childers' project was rare for an MFA applicant, it's just as unusual for a translator. Ní Mheallaigh puts his achievement into perspective: "What makes Chris's translation distinctive is that he's translating such a disparate body of material," she explains. "This is an uncommon project, and one of the great things about it is that it brings together materials that would otherwise be difficult for the reader to find gathered in one place."

She adds, "I suspect this is going to make the world of ancient Greek and Latin lyric poetry much more accessible than it ever has been."