Swiss cities are more likely to accept densification when densification projects provide affordable housing and green spaces compared to densification that is implemented through reduced regulations for housing construction. By prioritizing a socio-ecological densification, extensive planning procedures and delays might be minimized.

In brief

- A new white paper by ETH researchers explains how Swiss cities and towns can implement densification in an environmentally and socially sustainable manner.

- Acceptance of housing densification increases when it is developed by public-sector and non-profit organisations, and when it focuses on affordable housing with green spaces.

- These preferences are not only evident in the Swiss metropolises of Zurich and Geneva, but in all 162 Swiss cities and towns.

The housing situation in Swiss cities and towns is currently the subject of intensive debate in politics and the media. Housing and densification is a key topic for spatial and urban planners - because, ultimately, they are tasked with implementing compact, inward settlement development that is mandated by the Swiss Spatial Planning Act (external pageSPA) since 2014. One of the core planning tasks is to coordinate the different demands on urban space such as housing, work, transport, leisure and recreation so that they complement each other wherever possible and create synergies.

At ETH Zurich, David Kaufmann, Professor of Spatial Development and Urban Policy, focuses on the challenges when densifying cities. His research group (SPUR) investigates aspects of planning instruments and housing production, how densification can be implemented democratically and how densification is changing the socio-economic population composition of neighbourhoods and thus the urban fabric.

Example: new construction displaces low-income individuals around railway stations

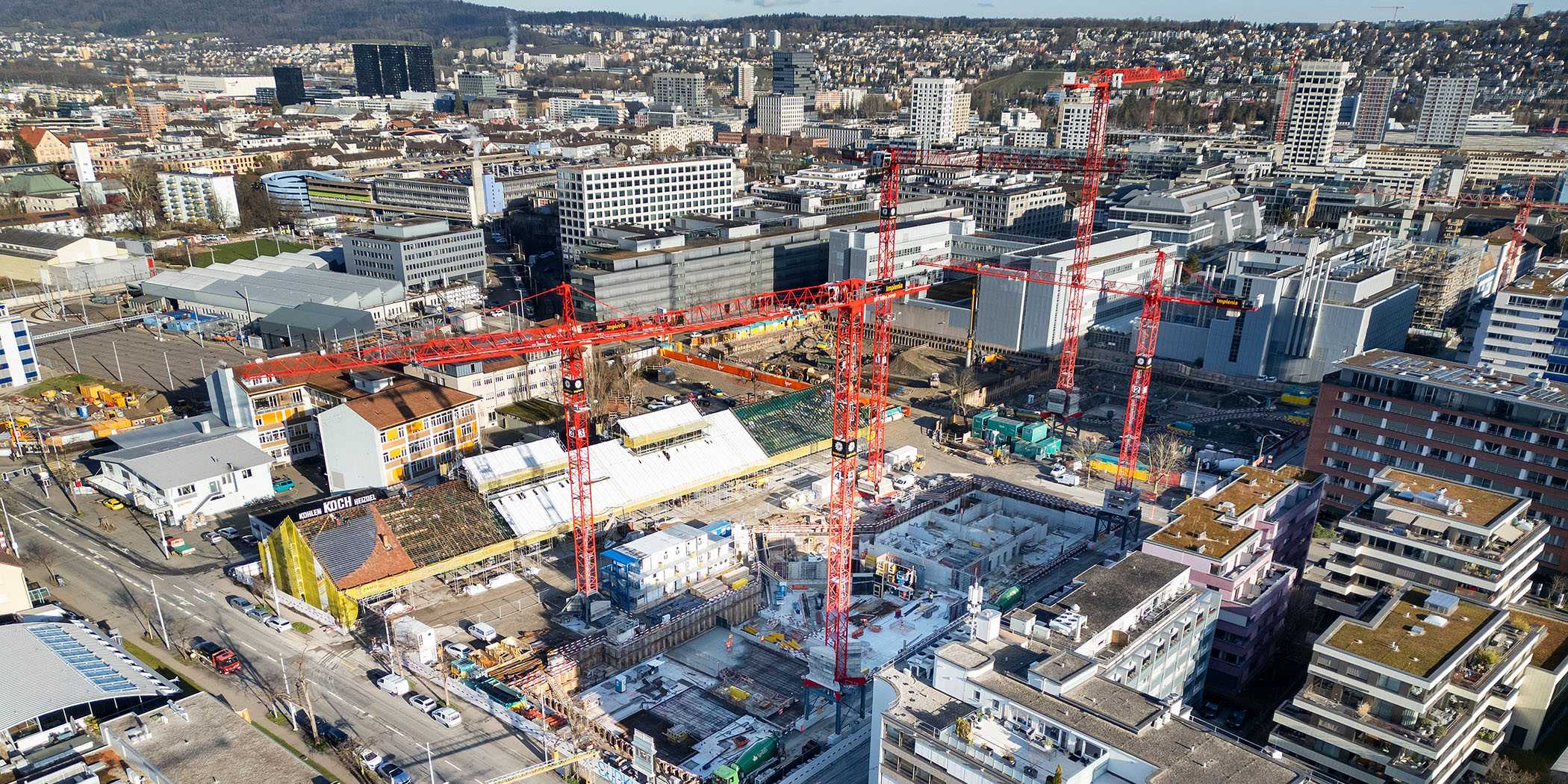

Across several publications, the group has shown how the demolition of old affordable housing (mainly the ones dating from the 1950s to the 1970s) and their replacement with new, usually more expensive housing leads to displacement effects. This is because people on lower and middle incomes that live in these buildings get evicted and can no longer afford the higher rents. Last week, the group published external pagea research paper in which it shows that these displacement effects occurred around the 49 major railway stations in the canton of Zurich between 2010 and 2020 (see references). They also published two reports last year on how the phenomenon of displacement through new buildings and renovations of buildings manifests itself throughout the canton of Zurich (see Zukunftsblog, 21.03.2023).

Because densification projects often face resistance, the SPUR group is systematically investigating how public opinion and policy decisions influence the acceptance of densification in cities and towns. For the Swiss National Science Foundation project "Densifying Switzerland" (2021-2025), ETH researchers are evaluating every referendum related to spatial planning from 2002 to 2020 external pagefor all 162 statistical cities and towns in Switzerland. Based on these local referendum results, they are examining the political acceptance of densification measures.

Lack of acceptance despite political approval

Since public opinion changes over time and may differ from referenda outcomes, the researchers are also conducting representative surveys with inhabitants of all 162 cities and towns. "This helps us recognise the differences between the political acceptance of urban densification projects and informal acceptance among the population," explains Michael Wicki, a senior assistant in Kaufmann's team with a background in public acceptance research.

For example, densification is politically accepted in principle among the Swiss population and enshrined in the Spatial Planning Act. In practice, however, the acceptance of densification projects generally decreases when the project are implemented in close spatial proximity and changes to the neighbourhood become foreseeable. "Where there is a lack of acceptance for densification, people are often concerned about the quality, suitability and long-term consequences of a construction project," says Wicki.

Recommendations for acceptance-oriented densification

David Kaufmann's group has now summarised its findings in the white paper "Public Acceptance and Policy for Green and Affordable Densification". It is available on the SPUR website and is aimed at spatial planners and urban policy-makers. The report includes discussions of ongoing housing debates, findings on the acceptance of densification as well as policy recommendations.

The key findings:

- Acceptance of densification projects varies depending on the developer. Public-sector and non-profit developers are favoured over private individuals and institutional investors. Accompanying social and environmental measures can also have a positive influence on acceptance.

- While there is no rejection for densification strategies that want to reduce regulations for housing construction, they are much less popular than "green and affordable" densification strategies based on affordable housing and an increase in the proportion of green spaces.

- Climate protection and climate-adapted urban development enjoy widespread acceptance among the urban population.

- These preferences are evident not only in the largest cities such as Zurich and Geneva, but in all Swiss cities and towns.

In general, the researchers recommend that cities and towns strengthen the capacity of their urban planning teams so they can act strategically in urban development and pursue an active land policy to achieve environmental and social development goals. According to the current study findings, becoming active does not just mean introducing new policy instruments or regulations (e.g. land pre-emption rights); cities can also use existing policy instruments (e.g. zoning plans, added land value capture) to implement a socio-ecological densification.

Active land policy could also involve an effective implementation of the municipal building regulations in favour of a socio-ecological densification, the purchase of land by public actors, or an active communication strategy with private landowners which raises awareness and knowledge around the relevance of the topic. This may help to prevent obstructions and delays in construction as well as local resistance so the overarching goal of densification can be implemented effectively.

The researchers formulate specific recommendations for the financial global centers of Zurich and Geneva; large Swiss cities such as Lausanne, Basel and St. Gallen; medium-sized agglomeration municipalities such as Opfikon, Spreitenbach and Carouge; and medium-sized regional centres such as Chur, where the pressure for density remains lower but is likely to increase in the coming years.

"It is important that cities pursue an active land policy for eco-social densification"

Why is public acceptance important for urban densification?

Michael Wicki: It is not the built environment that brings a city to life, but the people who use it. That is why public acceptance is crucial for the success of a sustainable densification.

What is the most urgent task for cities and towns in the area of housing?

It is important for cities and towns to integrate environmental and social aspects into urban planning, to pursue an active land policy, and to provide financial incentives for high-quality inward settlement development. For example, they could incorporate new types of zones into their building and zoning codes or revise existing ones that not only set the basic parameters of use, but also environmental and socio-political objectives that prevent displacement effects caused by more expensive new housing.

What do you recommend for new housing construction or renovations?

Currently, replacement constructions outnumber softer ways of densification by six and a half times in the canton of Zurich. Our group's research shows that in the case of replacement construction, rents tend to substantially rise because older existing housing got demolished. This often leads to the displacement of existing tenants, whereas softer densification measures are more socially sustainable because tenants can stay in their apartments. These softer densification measures include adding up storeys, conversions, retrofitting and extensions.

References

Wicki, M, Wehr, M, Debrunner, G, Kaufmann, D (2024). Public Acceptance and Policy for Green and Affordable Densification. ETH Zürich. DOI: external pagehttps://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000658390

Lutz, E, Wicki, M, Kaufmann, D (2024). Creating inequality in access to public transit? Densification, gentrification, and displacement. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 0(0). DOI: external page10.1177/23998083241242883

Debrunner, G, Hengstermann, AH. (2023). Vier Thesen zur effektiven Umsetzung der Innenentwicklung in der Schweiz. DisP-The Planning Review, 59(1), 86-97. DOI: external page10.1080/02513625.2023.2229632

Kaufmann D, Lutz E, Kauer F, Wehr M, Wicki M (2023). Erkenntnisse zum aktuellen Wohnungsnotstand: Bautätigkeit, Verdrängung und Akzeptanz. Bericht ETH Zürich. DOI: external page10.3929/ethz-b-000603229

Lutz E, Kauer F, Kaufmann D (2023). Mehr Wohnraum für alle? Bericht ETH Zürich. DOI: external page10.3929/ethz-b-000603242