An international team of researchers conducted the first comprehensive review of urban climate change responses and the positive effects that adjustment may have on human health and wellbeing. Image: Higashi Hiroshima Campus, Hiroshima University

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased attention on links between public health and the planet's health - areas traditionally addressed in separate science and policy circles. Now, an international research collaboration conducted the first comprehensive review of urban climate change responses and potential human health improvements.

Their results were made available online on July 20 in Sustainable Cities and Society and will appear in the journal's November print edition.

Working from the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC) definitions of co-benefits to adaptation in human systems, the researchers analyzed 245 papers that investigated the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and the positive effects that adjustment may have on human health and wellbeing. It's the first comprehensive review of such studies.

"While health co-benefits of climate change adaptation are acknowledged, they are not well studied and explored in the literature," said first author Ayyoob Sharifi, associate professor in both the Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences and the Graduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering, Hiroshima University, Japan. "Accordingly, through a systematic literature review, this study aimed to inform planners and policy makers of multiple co-benefits of different urban climate change adaptation measures for health and wellbeing."

In their 2019 search for papers on observed or modeled climate adaptations in cities, which continue to grow across the globe, the researchers excluded any climate-related studies that did not explicitly identify a health impact. According to Sharifi, relevant papers may have been published since their search, but the 245 studies they analyzed is a large enough sample to identify patterns and make conclusions.

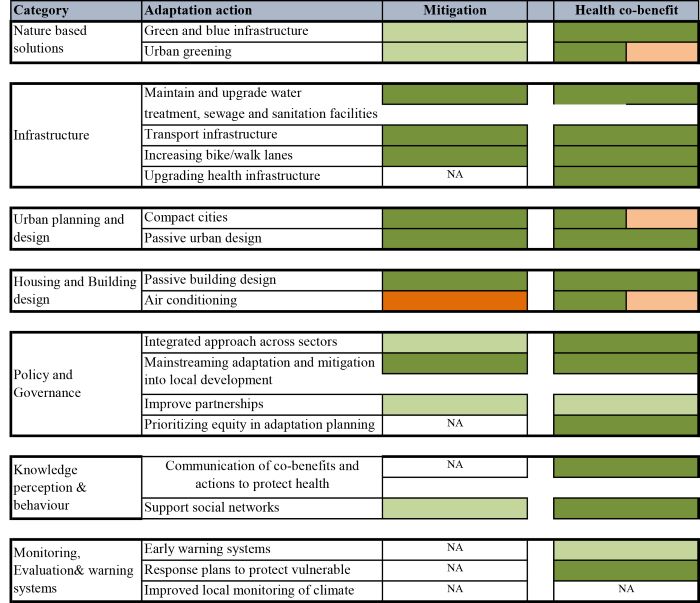

The researchers identified health co-benefits of seven categories of adaptation measures: critical and health infrastructure; nature-based solutions; housing and building design; urban planning and design; early warning systems; policy and management governance; and knowledge, perception and behavior. Of the studies analyzed, 105 papers verified the evidence of positive impact of adaptation strategies; 91 papers confirmed health as a primary co-benefit, and 48 papers highlighted health as a secondary co-benefit.

"Depending on the adaptation measure, different health co-benefits such as reduced cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, decreased heat stress, reduced exposure to food and water-borne diseases and enhanced mental health can be achieved," said paper author Minal Pathak, senior scientist in the IPCC Technical Support Unit of the Working Group III and in the Global Centre for Environment and Energy, Ahmedabad University, India. "The results showed that most adaptation actions lend themselves to positive health outcomes. Findings from this paper can provide insights to local policymakers on prioritizing urban policies and actions in the short-, medium- and long-term. For example, early warning systems, including heat warnings or flood warnings, can help deliver immediate benefits."

The researchers said they plan to conduct more empirical research on the nexus of health and climate change adaptation to better understand health co-benefits as a key outcome for mitigation in cities. They also plan to further investigate trade-offs between climate and health, such as the environmental cost of air conditioning, which reduces heat stress for people.

Other contributors include Chaitali Joshi, Global Centre for Environment and Energy at Ahmedabad University and the Department of Architecture at The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, India; and Bao-Jie He, School of Architecture and Urban Planning and Key Laboratory of New Technology for Construction of Cities in Mountain Area, Ministry of Education, Chongqing University, China.

The research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Major adaptation measures and their potential linkages to health and mitigation

Shades of green represent co-benefits while orange represent trade-offs. The intensity of colors represents the confidence attached to the finding. This is indicated by evidence from studies and agreement among authors. A darker color would indicate more confidence in the association. Blank boxes indicate insufficient knowledge/evidence.

About the study

Journal: Sustainable Cities and Society

Title: A systematic review of the health co-benefits of urban climate change adaptation

Author: Ayyoob Sharifi, Minal Pathak, Chaitali Joshi & Bao-Jie He