An Alaskan town facing erosion and sea level rise had to abandon its airport and repurpose the runway for housing. While erosion is currently the biggest threat to Arctic coastal infrastructure, sea level rise will be a growing problem for communities like this one, according to a new study in Earth's Future. Credit: Grid Arendal

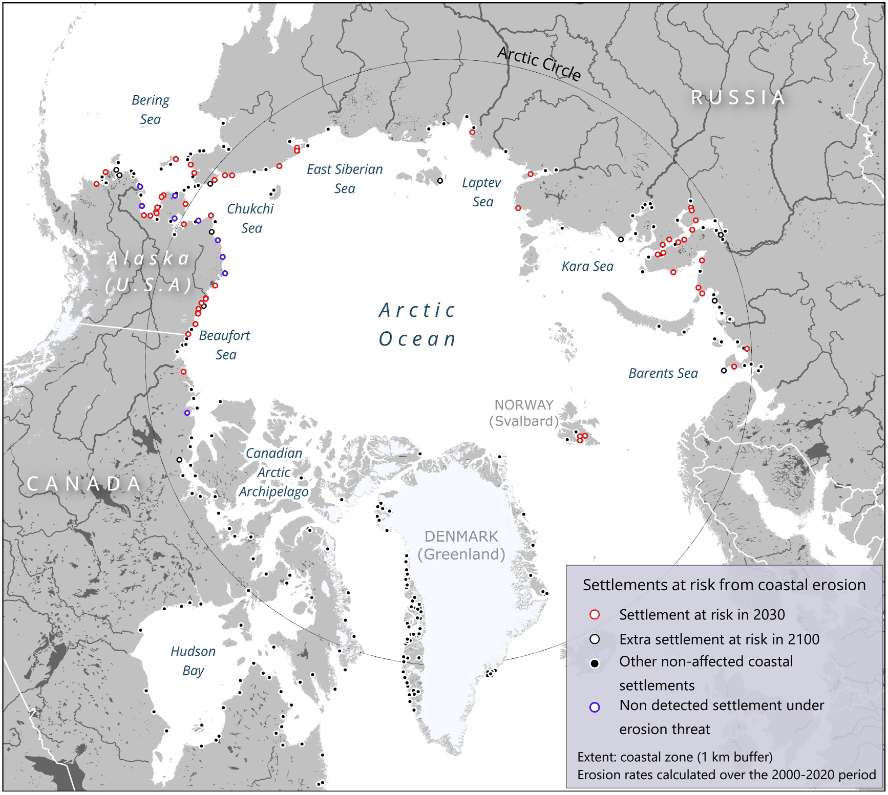

A new study has produced the first map of all coastal communities and infrastructure across the Arctic, showing the vulnerability of the built environment to threats from climate change. Erosion is currently the biggest threat to Arctic coastlines; some places are already experiencing erosion up to 20 meters (67 feet) per year. But rising seas and shifting storm patterns are predicted to emerge as threats in coming decades, accompanied by the ever-present threat of permafrost thaw.

The study finds that by 2100, 21% of the 318 settlements that now exist on Arctic permafrost coastlines will face damage because of coastal erosion; 45% will be affected by sea level rise; and 77% of the Arctic infrastructure potentially will sit on ground that is no longer frozen solid but crumbling and subsiding.

The work was published in Earth's Future, which publishes interdisciplinary research on the past, present and future of our planet and its inhabitants.

Many scientists monitor threats to the natural environment north of the Arctic Circle (66.33°N), but little attention has been paid to the human presence there, said Annett Bartsch, the founder of the Earth research and development company b.geos, who directed the study. "The number of people living along the Arctic coasts is comparatively small, but these people are highly affected by climate change, especially the Indigenous communities," she said.

To explore what kinds of infrastructure are in the Arctic and what threats they face, the researchers combined satellite and other data sources to map coastal erosion rates, sea level rise projections, and permafrost temperatures and thaw rates for 2030, 2050, and 2100.

Red dots indicate settlements at risk of instability due to erosion as soon as 2030, according to the new Earth's Future study. Black open dots indicate settlements that will be at risk by 2100. Credit: Tanguy et al. (2024)

Traditional communities with economies based on hunting and fishing make up 53% of Arctic settlements, the study found. Mining facilities make up another 20%, with military installations, tourist services and research stations rounding out the total. "A lot of this infrastructure serves people living farther south," rather than those living nearby, Bartsch pointed out.

The new map shows that today, erosion is the dominant threat to coastal communities, with coastlines near these settlements retreating an average of 3 meters (10 feet) per year across the Arctic. In some places, erosion rates are as fast as 20 meters (67 feet) per year.

"Settlements are already impacted by the increased rate of coastal erosion," Bartsch said. "More buildings and roads will be affected by 2030."

While the problem of coastal erosion is already apparent, the future impacts of rising sea levels was a surprise to the researchers. Relative sea levels are currently falling throughout the Arctic because of ice mass loss and post-glacial rebound, so relatively little research has been done on future sea level rise.

"People usually talk about sea level rise in other regions, not regarding the Arctic," Bartsch said. "But if one looks at the numbers, more Arctic settlements will be affected by sea level rise than by coastal erosion over the long run."

The hazards explored in the study can be compounded by other climate threats, such as changing weather patterns and land subsidence.

"That can result in very important shifts in the coastline in some areas," said Rodrigue Tanguy, a researcher at b.geos and first author on the study. "For example, along the coasts of Alaska, Canada and Siberia, there is a huge number of lakes on permafrost. If subsidence and erosion trigger breaches in these lakes, there will be a totally different coastal landscape."

#

Notes for journalists:

This study is published in Earth's Future, an open-access AGU journal. Neither this press release nor the study is under embargo. View and download a pdf of the study.

Paper title:

"Pan-Arctic assessment of coastal settlement and infrastructure vulnerable to coastal erosion, sea level rise, and permafrost thaw"

Authors:

- Rodrigue Tanguy (corresponding author), Annett Bartsch (corresponding author), Barbara Widhalm, Clemens von Baeckmann, b.geos GmbH, Korneuburg, Austria; and Austrian Polar Research Institute, Vienna, Austria

- Aleksandra Efimova, b.geos GmbH, Korneuburg, Austria

- Ingmar Nitze, Anna Irrgang, Pia Petzold, Julia Martin, Birgit Heim, Mareike Wieczorek, Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Potsdam, Germany

- Julia Boike, Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Potsdam, Germany; and Department of Geography, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany

- Gonçalo Vieira, Centre of Geographical Studies, Associate Laboratory TERRA, Institute of Geography and Spatial Planning, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

- Dustin Whalen, Geological Survey of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Dartmouth, NS, Canada

Guido Grosse, Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Potsdam, Germany; and University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

AGU (www.agu.org) is a global community supporting more than half a million advocates and professionals in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, AGU aims to advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.