People can contribute to Cyclone Alfred beach recovery efforts through a citizen science photo project founded by UNSW researchers called CoastSnap.

As parts of Australia's east coast get on with the clean-up from Cyclone Alfred, there's a simple way anyone can take part in coastal recovery, thanks to a project started by UNSW researchers.

There are more than 600 CoastSnap stations placed at beaches across the world. Many of these stations monitor pockets of Australia's eastern coastline affected by the recent weather event.

To participate, you place your phone in the cradle (pictured at the top), take a photo, follow some prompts and upload the picture to a database.

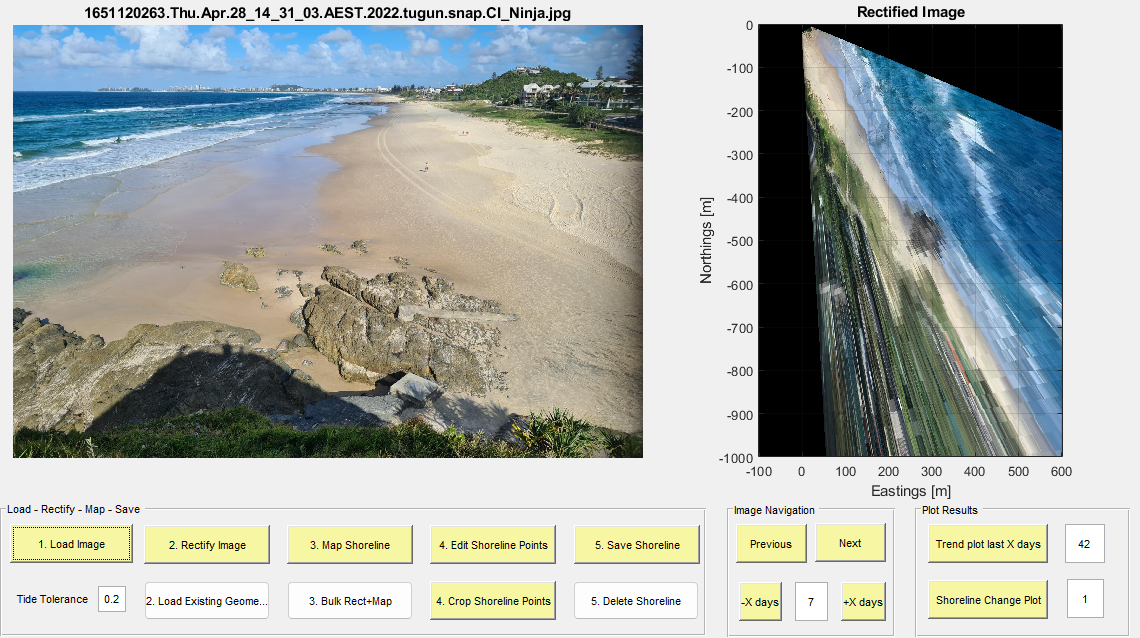

The photos are then modified by software to replicate photos taken from space and can be superimposed on actual satellite imagery.

(A photo taken from the Elephant Rock CoastSnap station edited into its 'satellite' form with the program its researchers use. Photo: Mitchell Harley/UNSW)

Even in their original form, the photos are valuable for monitoring the width of a beach.

YouTube: CoastSnapManly Community Beach Monitoring: May 2017 - Feb 2019

Mitchell Harley, Associate Professor with UNSW's School of Civil & Environmental Engineering and a co-founder of CoastSnap, says anyone with a smartphone can contribute and the more the merrier.

"Having these stations, where we can basically crowd-source and harness all of the smartphones that people have in their pockets, to get these eyes on the ground and get a lot more visual records of the changes up and down the coast, is really crucial."

A/Prof. Harley says the photos, once modified with the software, can be "equivalent to things you get from professional survey techniques".

Over 100,000 photos taken for CoastSnap since 2017 have helped provide a continuous picture of beaches for UNSW's Water Research Laboratory (WRL). The photos are open-source and placed on a world map on the CoastSnap website.

Recording Alfred and its aftermath

(A timelapse camera monitoring The Spit on the Gold Coast from Surfers Paradise during ex-Cyclone Alfred. Credit: UNSW Water Research Laboratory/City of Gold Coast)

Timelapse video taken by the WRL for the City of Gold Coast during the weekend Alfred hit, just after it was officially downgraded to an east coast low, shows a steady surge eating away at the coastline.

Photos from CoastSnap stations in nearby areas show the before and after.

(Before and after Cyclone Alfred at North Burleigh, 40 minutes' drive south from The Spit on the Gold Coast. Photos: UNSW)

A/Prof. Harley says continued efforts to use CoastSnap are important, even though Alfred is long gone.

"We're still in tropical cyclone season.

"As we go into April and May, we start to get extra tropical cyclones, the east coast lows… that's where we can see these really extreme effects… clusters of back-to-back storms that keep eroding the beach and there's no opportunity for that recovery phase to kick in."

He says documenting the recovery phase through CoastSnap is vital for preparation against the next event.

"Having those regular snaps really helps us understand how quickly beaches recover. Each beach is unique in that sense. Some beaches may recover in a matter of a few months. Others take a lot longer.

"You're contributing to a dataset without having to do much."

(Scenes before and after Alfred at Tallabudgera, 10 minutes' drive south of North Burleigh. Photos: UNSW)

CoastSnap's impact

CoastSnap started after massive storms in Sydney's north caused significant erosion at Collaroy Beach in 2016. Homes were damaged and left teetering on the edge of sand walls, with a council damage bill reported around $25 million.

"We had fixed cameras at certain locations … but [that event] really showed us we had lots of gaps," A/Prof. Harley says.

A pilot project, funded by the NSW government, monitoring that area was a success and became CoastSnap.

In a full-circle moment for the project, A/Prof. Harley says there hasn't been an erosion event on the scale of Collaroy until Alfred.

Now, a network of stations across the country gives the WRL a 'wealth of data' to assist its research, which informs policymakers.

Port Macquarie Council, in northern NSW, uses CoastSnap at Lake Cathie, a coastal lagoon, to detect when a sandbank has eroded far enough to let them legally dredge up sand from elsewhere and top it up.

(Lake Cathie, a coastal lagoon in mid-northern NSW near Port Macquarie. Photos: UNSW)

"That was all being informed by the community images, which I think is really nice, because it's kind of closing that loop. You have community collecting the data that are informing the decisions that affect the community."

One CoastSnap station, at the request of the NSW government, monitors a shipwreck that reveals itself after major storms at Woolgoolga on the state's mid-north coast. Alfred was the latest event to bring the 'Buster' wreck out into the open.

(A shipwreck revealing itself at Woolgoolga, near Coffs Harbour in NSW, after Alfred washed a lot of sand away. Photos: UNSW)

CoastSnap's journey out to international waters has also provided other uses for the cradles. The project monitors a harmful form of seaweed called sargassum in the Caribbean, West Africa and Mexico.

"It just comes in massive clumps, beaches itself and completely disrupts the tourism and fishing industry. [These places] are really interested in understanding these events," A/Prof. Harley says.

Expansion plans

Artificial intelligence is complementing CoastSnap in many ways, from speeding up processes to providing even more uses for the photos.

"There are new algorithms being processed which just allow us to do what we were doing a few years ago much faster and more accurately."

A/Prof. Harley is also working with Surf Lifesaving Australia on an app that uses CoastSnap photos to detect rips. The amount of images available through the project is a valuable asset for helping AI detect the currents.

While that's still in the works, A/Prof. Harley encourages people to be a part of CoastSnap where they find it.

"What we find is that once you build up that visual record, then forever more we have that record to inform policy."

(The view from CoastSnap's cradle at Cape Byron overlooking Byron Bay, NSW. Photos: UNSW)

Key Facts:

People can contribute to Cyclone Alfred beach recovery efforts through a citizen science photo project founded by UNSW researchers called CoastSnap.