For a few days once a year, when conditions are just right, our entire Great Barrier Reef bursts into new life with the synchronised release of millions of reproductive bundles. Spawning is truly one of nature's greatest spectacles, creating new, genetically diverse life on our Reef as baby corals form, settle and grow.

Yet, this unique reproductive behaviour can also be limiting for reef restoration efforts. Spawning events are a fleeting window of opportunity for research teams who work around the clock to collect spawn, and use it to grow new, resilient corals either 'on reef' or in special aquariums on land.

Building up a 'bank' of viable coral reproductive material during the spawning season can help to ramp up efforts outside of the short 'fertility window' - that's where cutting edge cryopreservation techniques could help. Precious samples of coral genetic material are collected during the annual spawning event and immediately 'put on ice'. These are then added to the world's largest frozen repository of living coral at Taronga's CryoDiversity Bank, where they are stored in chambers of liquid nitrogen at -196°C.

The aim is to not only protect biodiversity but also use cryopreservation to support a scaled-up coral aquaculture industry, meaning more corals can be grown and then deployed to help rebuild and restore damaged reefs. The work is part of the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP) which is the world's largest effort to help a significant ecosystem survive climate change.

Explainers ·

What is coral cryopreservation?

The RRAP Cryopreservation team have trillions of cells from a variety of Great Barrier Reef species in their CryoDiversity Bank and during spawning in 2022, for the first time, the team also froze and then reanimated Great Barrier Reef coral larvae.

The process is challenging, because coral larvae cells are full of fat, meaning ice crystals often form when they are frozen, which can pierce and damage the cells. Freezing and then reanimating these larvae aims to make a huge number of coral larvae available outside of the spawning window, further accelerating our ability to grow baby corals throughout the year.

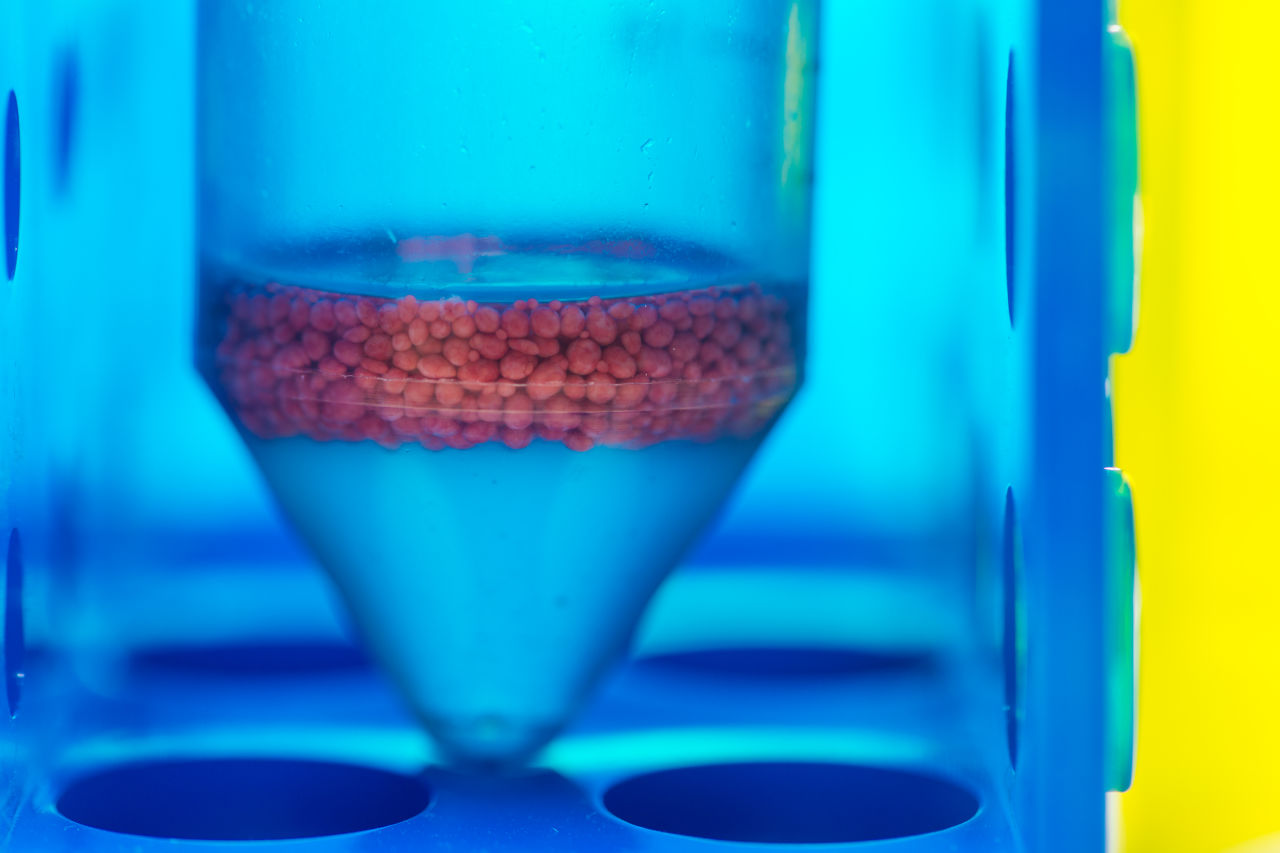

Gathering coral gametes in test tubes for the cryopreservation process. Photo: Gary Cranitch

A Trans-Pacific collaboration was critical to the breakthrough. Project lead Dr Jon Daly, from Taronga Conservation Society Australia, and his team collaborated with researchers from the Smithsonian Institution, and importantly, with an engineering team from the University of Minnesota who developed the low cost larval freezing technology known as 'cryomesh'.

Taronga Conservation Society researchers Jonathan Daly, Rebecca Hobbs and Justine O'Brien with collaborators from the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, Mary Hagedorn and Mariko Quinn.

Fast, easy-to-use and cheap solutions like this, mean that normally high-tech coral cryopreservation methods can be shared across regions that may not have the extensive scientific research facilities of Australia and the Great Barrier Reef.

As the team prepare for the 2023 spawning, they'll be bringing even more learnings from international collaboration to the table. Their visit to Florida Aquarium in mid-2023, in collaboration with the Smithsonian Institute and the University of Minnesota, saw the advancement of the larvae-freezing technique using a Pacific coral that has larvae similar in size to an important Great Barrier Reef coral species, often used for reef restoration here in Australia.