Despite a dearth of funding, the Rutgers Health-led hotline remains the go-to well-being resource for New Jersey's law enforcement professionals

Michael Runyon ran through his options. Gripping the wheel of his Jeep Grand Cherokee one morning in July 2014, the Trenton police officer could either enter the liquor store he'd frequented countless times after overnight shifts, grabbing a bottle to blur the violent images racing through his mind.

Or he could do as a friend had urged him: Pick up the phone and call Cop2Cop.

"Speaking to Cop2Cop, having one of the peers support me in my desire to get better, led me to make the decision to go into rehab," said Runyon. "I haven't had a drink for 11 years because of that call."

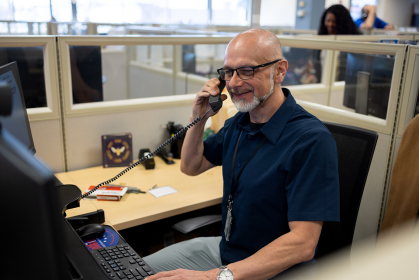

Runyon is among thousands of New Jersey law enforcement professionals who have leaned on the program since its founding in 2000. Operated by Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care (UBHC) and staffed exclusively by retired officers - including Runyon, who was hired as a peer support specialist after his retirement from Trenton in 2016 - Cop2Cop offers a confidential outlet where active-duty police can talk to peers without judgment.

On March 21, the program marked 25 years of service, a milestone both for its achievements and for its ability to persevere amid limited financial resources.

Cop2Cop fields more than 3,000 calls a year, and its direct interventions have saved hundreds of lives.

Cop2Cop fields more than 3,000 calls a year, and its direct interventions have saved hundreds of lives, according to program leaders.

Initially created as a suicide prevention hotline, the reciprocal peer support program - in which people with lived experience and trained in behavioral health help their peers - has evolved into the state's premiere resource for police and law enforcement officers needing help with job-related depression, anxiety, stress or other traumas. Direct support is available around the clock by phone, text, email, social media and live chat. With UBHC guidance and oversight, staff also conduct in-person de-briefings, sessions with officers to discuss anything that might be troubling them.

The most recent de-briefing was held in Newark, after city Detective Joseph Azcona was killed on duty by a 14-year-old assailant on March 8.

"We just give them a chance to talk about how they're feeling, what they're feeling and let them know that we're here to support them," said Sabrina Howard-Mills, a Cop2Cop peer support specialist and retired police detective.

As Cop2Cop's reach has widened, the workload has increased proportionally.

"When we first started, we simply picked up the phone," said Irena Guberman, director of call center operations at the UBHC National Call Center, which administers the Cop2Cop program and several other hotlines (including helplines for military veterans, firefighters and paramedics). In-person support is now a large part of the Cop2Cop programming, she added.

Every police academy recruit today receives mental health resiliency training - delivered by Cop2Cop. In 2019, the state launched a resiliency program, placing well-trained cops in departments to serve as well-being advocates.

Despite the need and its expanding scope, Cop2Cop's budget hasn't changed since inception. Created by legislation after a series of police suicides in the late 1990s, lawmakers wanted a telephone hotline. An annual budget of $400,000 was allocated to cover salaries - peer supporters are paid employees, not volunteers - equipment and training needs. The budget hasn't moved since.

What has changed over the past 25 years is New Jersey's response to police mental health. Every police academy recruit today receives mental health resiliency training - delivered by Cop2Cop. In 2019, the state launched a resiliency program, placing well-trained cops in departments to serve as well-being advocates. More than 1,400 of these officers currently work in police departments throughout the state, liaising with Cop2Cop on serious cases.

New state legislation introduced this session would create a Cop2Cop sustainability fund and add an additional $500,000 to the budget, bringing annual funding to $900,000. Mark Graham, a retired Army general and executive director of the National Call Center, said the funding - which would help ensure staffing levels keep pace with need and cover rising administrative costs - is long overdue.

"We scrape by every year," Graham said. "We really need this money."

One reason why: Police are encouraged to talk about stress, a shift from past generations when officers were expected to be stoic, suffering in silence. This shift has only deepened the state's reliance on the Cop2Cop network.

"It may be an officer who's transferred to special victims and has never dealt with a baby case, and they may be struggling," Howard-Mills said. "Or they may just be having a bad day and really need to talk to someone. We've all been there."

Runyon certainly has.

New state legislation introduced this session would create a Cop2Cop sustainability fund and add an additional $500,000 to the budget, bringing annual funding to $900,000. The funding - which would help ensure staffing levels keep pace with need and cover rising administrative costs - is long overdue.

For him, the journey from rock bottom to peer counselor began several years before he picked up the phone.

"I'd been in an ambush, sometime in 2012," Runyon recalled. "A guy with an assault rifle opened fire on me and my partner. Somehow, the bullets missed us, but they peppered our vehicle. That moment sent me into a downward spiral with PTSD and alcoholism."

Days after that shooting, Runyon returned to work. His department assigned him the same car, the one riddled with bullet holes - patched only to keep out the rain.

Two years later, the dam burst.

"It was a Sunday morning, 5:30 a.m., my last shift of the weekend before four days off," Runyon said. "Driving up a side street, we saw a man running toward us. There were gunshots. I saw him get hit. He spun, fell to the ground."

Runyon jumped out of the car.

"I did CPR," he said. "But there were six bullet holes in his back. I couldn't save him. For some reason, that failure broke me."

Three days later, after replaying the incident over and over in his head, Runyon found himself sitting in his car outside the liquor store. He wanted to go in, but something stopped him.

As a cop, Runyon kept everything bottled up.

"Now, I talk to everybody about my secrets," he chuckled. "Doing this, working for Cop2Cop, healed me more than anything else. Helping others is now my calling."