Our first batch of Coral IVF babies, which we grew from microscopic larvae and planted on the Reef in 2016, have reproduced for the first time, giving hope that this innovative technique could successfully restore damaged reefs.

In an exciting development, researchers revisited 22 large coral colonies around Heron Island that were born through the first Coral IVF trial on the Great Barrier Reef and noted they have survived a bleaching event and grown to maturity.

In this year's coral spawning event, they produced their first batch of coral larvae, or baby corals.

This is the first time a breeding population has been established on the Great Barrier Reef using this ground-breaking process.

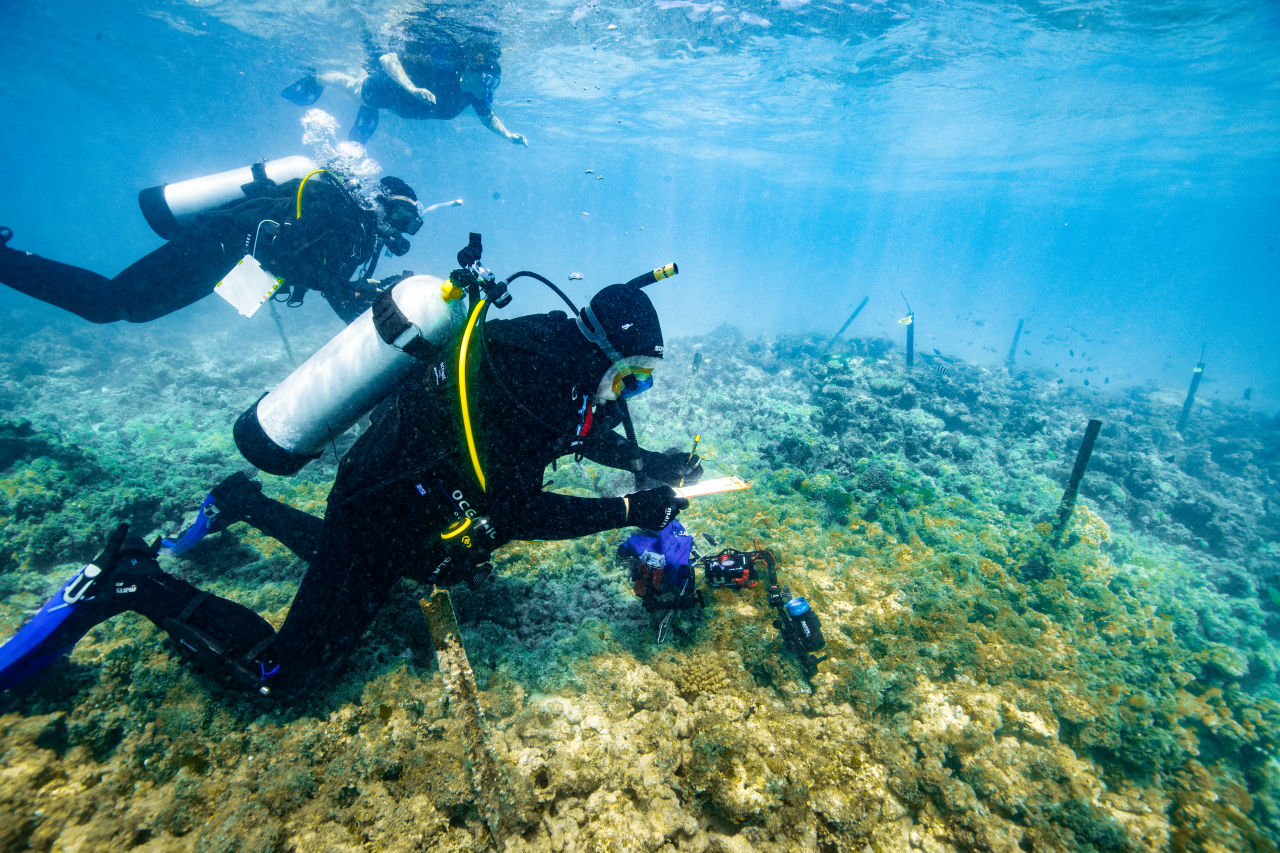

Peter Harrison revisiting the 2016 Coral IVF babies planted around Heron Island, which have reproduced for the first time. Credit: Southern Cross University

Coral IVF is a world-leading technique to grow baby corals and use them to restore damaged coral reefs. Our researchers capture coral eggs and sperm, called spawn, from healthy reefs and rear millions of baby corals in specially-designed floating pools on the Reef and in tanks. When they are ready, we deliver them onto damaged reefs to restore and repopulate them.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation Managing Director Anna Marsden said the results are promising.

"We couldn't be more excited to see that these coral babies have grown from microscopic larvae to the size of dinner plates, having not only survived a bleaching event but are now reproducing themselves - helping to produce larvae that can restore a degraded reef," she says.

"After seeing the potential of this game-changing technique, the Great Barrier Reef Foundation and its partners brought Coral IVF to the Reef back in 2016 - bringing together people and science to give nature a helping hand.

"Saving the Reef is a huge task, but having proof that this innovative, cutting-edge science works gives us hope."

The 2016 Coral IVF babies have grown to dinner plate size. Credit: Southern Cross University

Lead Researcher and Southern Cross University Distinguished Professor Peter Harrison said Coral IVF is the first project of its kind to re-establish corals on damaged reefs.

"The ultimate aim of this process is to produce new breeding populations of corals in areas of the Reef that no longer have enough live corals present, due to being damaged by the effects of climate change," Prof. Harrison says.

"This is a thrilling result to see these colonies we settled during the first small-scale pilot study on Heron Island grow over five years and become sexually reproductive.

"The larvae generated from these spawning corals have dispersed within the Heron Island lagoon and may settle on patches of reef nearby, helping to further restore other reef patches that have been impacted by climate change.

"This has given me and the rest of the team renewed enthusiasm as we research additional techniques on Lizard Island, through the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program in collaboration with CSIRO, QUT and with support from Australian Institute of Marine Science, that will enable us to scale up and optimise this technique."

The Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program is the world's largest and most ambitious effort to develop, test and deploy at-scale protection, restoration and adaptation interventions to ensure that the Great Barrier Reef and coral reefs globally can resist, adapt to, and recover from the impacts of climate change.