If carbon emissions are curbed and local stressors are addressed, coral reefs have the potential to persist and adapt over time. That's according to a study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB). These findings suggest that coral conservation in a changing world is possible-but urgent action is essential.

This work was conducted by the Toonen-Bowen "ToBo" Lab, with partners at UH Mānoa and The Ohio State University.

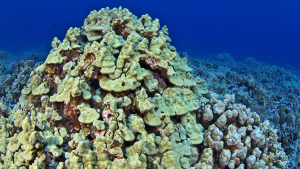

HIMB researchers created 40 experimental systems known as "mesocosms," which mimic the environment of a coral reef in the wild. The mesocosms included eight Hawaiian coral species, reef sand, rubble and marine creatures, representing one of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet. For two years, the team exposed the mesocosms to different scenarios of higher temperature, higher acidity or a combination of both ocean stressors to see how the reef communities would react to future climate scenarios.

"We included the eight most common coral species in Hawaiʻi, which constitute about 95% of the coral cover on Hawaiian reefs, and many of the most common coral types across the Pacific and Indian Oceans," said Christopher Jury, HIMB post-doctoral researcher and lead author of the study. "By understanding how these species respond to climate change, we should have a better understanding of how Hawaiian reefs and other Indo-Pacific reefs will change over time, and how to better allocate resources as well as plan for the future."

The team controlled levels of temperature and acidity in the mesocosms. They measured the calcification (where individual coral organisms build their own skeletons by secreting a salt known as calcium carbonate) responses of the coral reef communities and the biodiversity of these systems.

"These experimental reef communities persisted as new reef communities rather than collapsing," said Jury. "This was a very surprising result, since almost all projections of reef futures suggest that the corals should have almost entirely died, the reef communities should have experienced net carbonate dissolution, and reef biodiversity should have collapsed. None of those things happened in this study."

"Rather than focusing on just one or two species in isolation, we included the entire complement of reef species from microbes, to algae, invertebrates, and fish, under realistic conditions they would experience in nature," said Rob Toonen, HIMB professor and Ruth Gates Endowed chair, and co-senior author of the study. "These more realistic mesocosm experiments help us to understand how coral reefs will change over time."