This article first appeared in the special feature Understanding the Impact of Climate Change.

15 questions for climate change researcher Dr. Tsuyoshi Watanabe (with subtitles)

Coral reef geo-environmental specialist Tsuyoshi Watanabe's research focuses on coral dating, the past global environment that can be reconstructed from this data, and the relationship between corals and human society. He spoke about what new value the unique properties of coral can teach us beyond its beauty.

The mysterious charm of corals

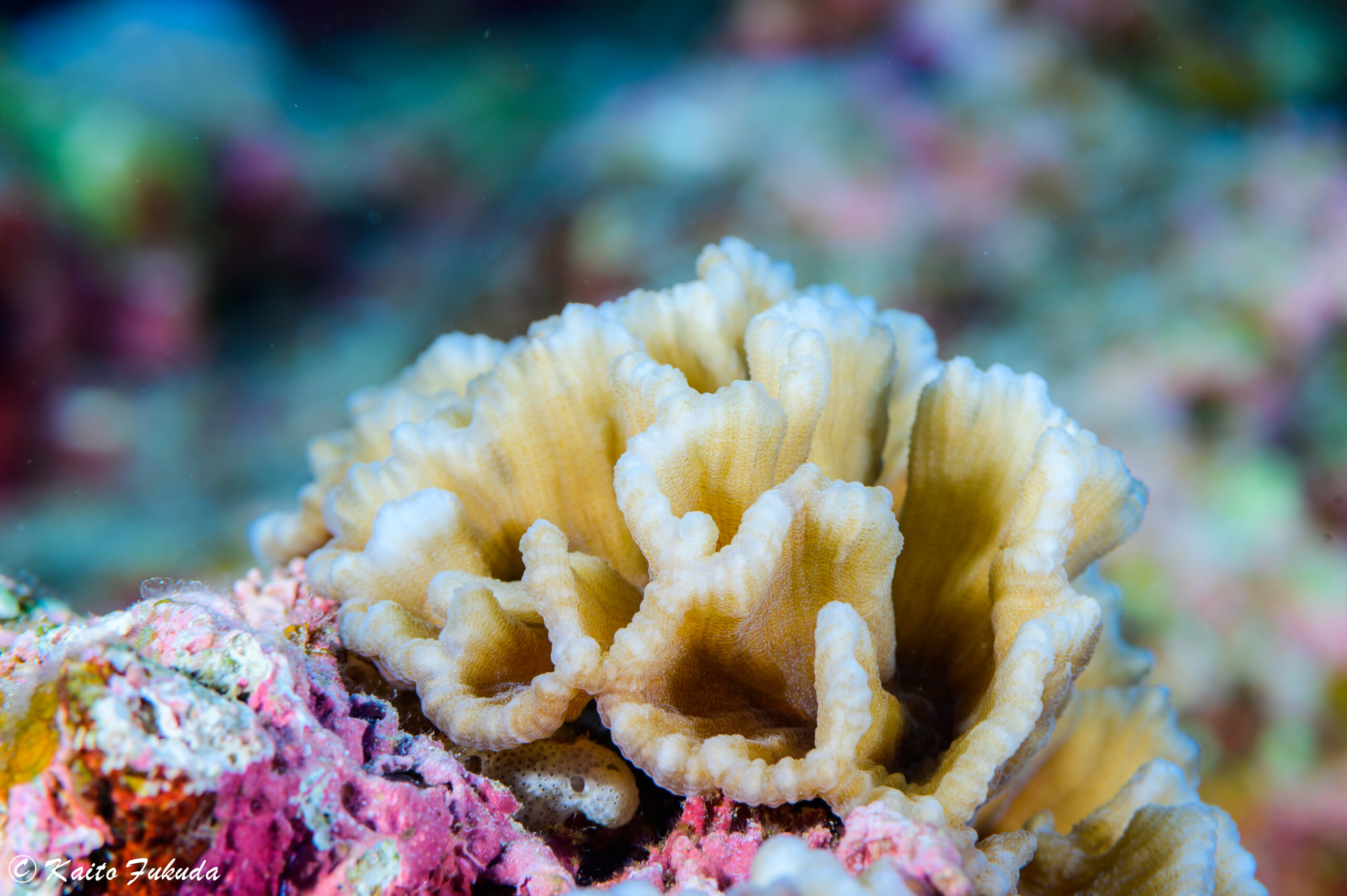

Corals are a type of animal classified in the phylum Cnidaria. They are mainly found in shallow waters in tropical regions and are very vivid and diverse in shape. I, too, feel soothed every time I see them during fieldwork and other activities.

Another feature of corals is their symbiosis with algae, called zooxanthellae. The zooxanthellae share the nutrients they produce through photosynthesis with the coral. The coral, on the other hand, provides a safe haven for the zooxanthellae in its cells-a mutually beneficial relationship. Corals also expel excess nutrients as mucus. This attracts micro-organisms and the fish and shellfish that prey on them to the surrounding area. In this way, a coral-based ecosystem is built up in the sea.

The lifecycle of corals is also very mysterious. They spawn around the time of the full moon. Once hatched, the larvae attach themselves to the seabed (called epiphytes) and begin to build a skeleton made of calcium. They then divide and grow larger, spreading out as a colony into various shapes. The resulting landforms are called coral reefs, which exist on a time scale of thousands of years after the coral has died. The famous Great Barrier Reef in Australia is the world's largest coral reef, with a width of over 2000 km.

The corals that have thus passed through the years are deeply engraved with the history of the global environment and human-created civilizations.

Tracing prehistoric climates through corals

We take the coral skeletons collected in the field back to our laboratory, where they are sliced into thin sections. When the resulting sections are radiographed, we can see the annual rings of the coral, similar to the cross-section of a tree. Samples from each ring are then ground into a fine powder and dissolved in phosphoric acid, which produces carbon dioxide. By ionizing this carbon dioxide and applying a magnetic field, the isotope ratios of oxygen and carbon (*1) can be determined. Ultimately, it is possible to estimate the environment-such as water temperature and precipitation-in which the coral was living at the time.

For example, ocean water (H2O) contains two isotopes, oxygen-16 (O16) and oxygen-18 (O18); O16 is more readily taken up by Antarctic ice sheets than O18; hence, the relative proportion of O18 in the ocean increases during glacial periods when temperatures are low and ice sheets are expanding. Corals take in oxygen from seawater when building their skeletons, so annual rings should contain more O18 when temperatures are cooler. This means that the isotopic ratio of oxygen can be used to determine the climate at the time.

*1 Isotope ratio: Isotopes are atoms that have the same atomic number but different numbers of neutrons. This ratio is strongly influenced by the environment of the time when the substance was created, so the isotope ratio can be used to infer the environment of the time.

The fall of the Akkadian Empire and climatic factors

It is not only the climate of the time that can be seen in coral. When combined with historical data, corals can also tell us about the lives of people in those times. Here is one interesting research result, regarding the fall of the Akkadian Empire, that we published in 2019.

The Mesopotamian civilization developed in West Asia and the country of Akkad was founded about 4,600 years ago. The Akkadian Empire flourished for about 400 years, but it was suddenly destroyed. Archaeological research and other studies have suggested that it was apparently related to climate change at the time, but the detailed causes were not known.

Chemical analysis of the coral fossils revealed what was going on at the time. The Akkadian Empire was located in a prosperous agricultural region, but isotope analysis of the coral shows that there was a period when the dry winter winds blew continuously for up to three months. We speculate that this prolonged dryness may have depleted irrigation water and made the area uninhabitable.

Kikai Island and the KIKAI Institute for Coral Reef Sciences

Kikai Island, where our research is based, is a small, remote island in Kagoshima Prefecture, with a population of approximately 7,000. The limestone soil made of coral reefs has a tendency to hold water, so there are springs all over the island and people live around them. Since ancient times, the island's inhabitants have eaten fish from the coral reefs and built walls and tombs out of coral. Each community has developed its own local songs and dances, and cultural diversity is very high. There is a sense as if the coral ecosystem in the sea has become an island where people live in harmony with nature.

This environment is also alive with the wisdom of the people who live on the island, and I feel that there are important clues in the search for a more sustainable relationship between people and nature.

In 2015, the KIKAI Institute for Coral Reef Sciences was opened on such an island of Kikai, using a closed primary school.

Here, our work is not limited to research alone, but also involves exchanging and disseminating information with a diverse range of people involved with the islands, and creating learning opportunities for children and young people. Coral reef research was originally conducted not only by natural science researchers, but also by archaeologists, anthropologists, sociologists and other researchers from various fields who took their own approaches. We thought it was important to make better use of the knowledge gained in this way.

KIKAI Institute for Coral Reef Sciences, built in an former primary school. (Photo coutesy of Tsuyoshi Watanabe)

Understanding the spirit of the past through theater

The story performed last year was set in September 1953, the year before Kikai Island was returned to Japan. At that time, Kikai Island, which was an American territory, was undergoing major social changes. In fact, we know from our coral skeletal records that there was no rainfall for about two weeks during that year, and September is just around the time of rice planting (*2). We created a historical narrative in theatre that interweaves the social changes in one settlement with our climate change data.

Researchers, artists and local people are working together to create it, but to do theater you need to express the images that are in each of our minds. If it were me, I would be thinking about the future based on coral analysis data, if I were an archaeologist, I would be thinking about ruins, and if I were an anthropologist, the history and culture of people would be at the base of my thinking. I am not a professional theater artist myself, so I sometimes get criticism from local people about my acting and dancing, or advice that their village has a different and more interesting culture. I feel that this creates opportunities for equal and rich dialogue that I cannot get from my everyday research alone.

I also realized that what we should interpret from the data is not just a prediction of the future, but also whether people's hearts and minds will properly follow this vision of society. It is important to think together about what kind of future we would like to achieve together or accept, rather than just slogans like 'stop carbon dioxide emissions' or 'stop the economy'.

Through theatre, we want to carefully look at what changes were made in the minds of the people who lived there in the past, and what kind of future the people who live here identify with.

*2 In the Amami region, rice is planted in two seasons, in spring and autumn.

A sustainable knowledge hub, following in the footsteps of coral

Coral larvae are only a few millimetres in size, and the time between spawning and attachement is about one week. However, some larger coral reefs can span thousands of kilometres and continue to exist on time scales of thousands of years.

We are all born alone. Then we start a family, get friends, establish settlements and countries, and so on. When you think about it this way, coral and people are very similar.

Both corals and people have gradually created the environment in which they live over time.

However, since the Industrial Revolution, people have been burning fossil fuels, which were created over a long period of time. This may be described as an alien movement that exceeds the original time scale of the natural world, including corals.

Corals have survived many of the cataclysmic changes that have occurred on the planet. Perhaps they may be able to adapt to some extent to the current global warming. However, if the rate of change that humans are bringing about is faster than the speed at which corals are adapting, we will still have a very tough future ahead of us.

I am now building a center for coral research and education on Kikai Island. I feel that what is happening here is a good cycle for both the researchers and the people living there. Recently, I have been approached to do this on other islands as well.

Eventually, we hope to gradually increase the number of locations and create an ecosystem that connects them. Just as Dr. Clark dreamed of an 'offshore university' where people could learn while travelling the world by ship. I believe that the wisdom gained from corals without borders will be the key to forming such a loose and sustainable knowledge base.

The Kikai Island Coral Reef Science Institute aims for sustainable development of coral reefs, people and natural science under the slogan 'For the next 100 years.'

The Kikai Island Coral Reef Science Institute aims for sustainable development of coral reefs, people and natural science under the slogan 'For the next 100 years.'

Research that not only thinks, but also practices and interactsSapporo Agricultural College, the predecessor of Hokkaido University, used to provide support by taking agricultural technology to Palau and Taiwan, which were then Japanese territories. When I was an undergraduate, my teacher at the time told me that the corals brought back from these exchanges were now being used for research. When I heard that, I thought it was interesting and that is when I started researching corals. This experience also informs my current approach to research. |

Written by Space-Time Inc.

Part of the special feature Understanding the Impact of Climate Change