A new study finds that cowbirds adjust the sex of their offspring throughout the nesting season. A female, left, and male cowbird perch on a wire fence. Both birds are adults.

Photo by Michael Jeffords and Sue Post

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Brown-headed cowbirds show a bias in the sex ratio of their offspring depending on the time of the breeding season, researchers report in a new study. More female than male offspring hatch early in the breeding season in May, and more male hatchlings emerge in July.

Cowbirds are brood parasites: They lay their eggs in the nests of other birds and let those birds raise their young. Prothonotary warblers are a common host of cowbirds.

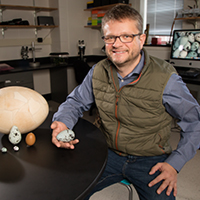

Illinois Natural History Survey researcher Wendy Schelsky uses molecular tools and ecological experiments to study life-history traits related to predation and parasitism.

Photo by L. Brian Stauffer

"Warblers can't tell the difference between their own offspring and cowbirds," said Wendy Schelsky, a principal scientist at the Illinois Natural History Survey and co-author of the study. "They do a really good job of raising cowbirds, even though cowbird chicks are larger and need more food."

The researchers studied the interactions between cowbirds and warblers for seven years to determine whether there was a difference in the relative number of males and females among cowbird offspring. They collected DNA samples from cowbird eggs or newly hatched chicks.

"Other scientists have not seen any difference in the sex ratios of brood-parasitic birds," said study co-author Mark Hauber, a professor of evolution, ecology, and behavior at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. "This is the first time anyone has detected a seasonal bias and we believe that it is due to our large sample sizes."

Mark Hauber, a U. of I. professor of evolution, ecology, and behavior and co-author of the new study, focuses on the evolution of sensory systems in birds to determine how individuals recognize themselves, their mates, their young, their prey and their predators.

Photo by L. Brian Stauffer

The researchers think their results may reflect the different developmental trajectories of male and female cowbirds.

"Male cowbirds take longer to mature and are unlikely to breed in their first year as adults," Schelsky said. "However, since most adult females breed in their first year, they have a better chance of being in good shape if they are produced earlier."

Although the eggs and newly hatched chicks both show the seasonal sex bias, it is unclear whether the differing sex ratios persist in birds that grow up and leave the nest.

"We have not looked at what happens to the chicks after they fledge," Hauber said. "We know that adult cowbird flocks are heavily male-biased, so perhaps increased mortality or dispersal by early-hatched female cowbirds impacts the eventual adult sex ratios."

More female than male cowbirds are hatched early in the nesting season, and the pattern is reversed in July, new research finds. An adult female cowbird, upper right, perches on tree stems above an adult male cowbird.

Photo by Michael Jeffords and Sue Post

The researchers hope to understand the molecular mechanisms that female cowbirds use to influence the sex of their offspring.

"It would be interesting to know if the females change their hormone levels across the season to influence the sex ratio of the eggs," Hauber said.

Cowbirds are successful in part because they leave the care of their offspring to other birds.

Photo by Michael Jeffords and Sue Post

The researchers report their findings in the Journal of Avian Biology. First author and former Illinois postdoctoral researcher Matt Louder is now at H.T. Harvey & Associates in Los Gatos, Calif.

The INHS is a division of the Prairie Research Institute at the U. of I.