The next time you're on an office scavenger hunt or trying to find your way out of an escape room with your co-workers, just remember that every second of shared experience helps tighten cybersecurity within your organization.

That thought may never have occurred to you while on a team-building event, but research from a group of professors from the University of Virginia's McIntire School of Commerce shows a new, important benefit to organizational bonding.

McIntire's Brent Kitchens, Steven L. Johnson and Ryan Wright, with support from UVA Chief Information Security Officer Jason Belford, recently published the article, "Phishing Susceptibility in Context: A Multilevel Information Processing Perspective on Deception Detection." The article explains why employees fall victim to phishing email scams that compromise the security of their organizations, despite a heightened awareness of security. It's estimated that 70% to 90% of all cybersecurity breaches start with phishing emails.

They tested their hypotheses in a study where employees of the finance division of a large university encountered simulated email-based phishing attempts as part of their normal work routine.

Among their conclusions is that companies, in addition to investing in phishing training, should invest resources into creating collaborations and connections between employees. It's approaching phishing-attack prevention as a "team sport," Kitchens said.

"No organization," Kitchens said, "is thinking right now, 'Hey, we should do some team-building to increase our cybersecurity resilience.' But that's what they should be doing. That's exactly the type of thing that is going to create better resilience."

Phishing is a type of scam where attackers use deception to get people to reveal sensitive information. In a workplace, an employee's vulnerability to a phishing attempt could lead to severe consequences for an organization.

UVA Today caught up with Kitchens, Johnson and Wright to learn more about their research and the benefits of a more collaborative work environment.

Q. If you're socially isolated within an organization, how can that impact your susceptibility to a phishing attack?

Johnson: One of our findings was that an isolated person within an organization is more susceptible to a phishing email attack. It's as simple as, when a potentially suspect email arrives in the inbox, if that person doesn't have a lot of interactions with other people at work, they might not have someone easy to ask about the risk.

Or that person might be so focused on just getting tasks done that they don't question whether that's a task worth doing. If they see their job as just, "I'm going to sit here in the organization and respond to incoming stimuli and answer every email," then they're vulnerable.

But if you're plugged into an organization and plugged into the workflow, you understand the bigger objective and you might be like, "This little thing that I'm being asked to do in this email, like that just seems weird. It doesn't seem to me like it would be helpful."

Kitchens: The less you're connected, the less you're going to feel confident or comfortable making these decisions and you're going to make mistakes.

And so that's exactly the type of interaction that we would say, based on this research, you need more of: Having people have informal conversations, reaching out, being able to ask questions, go out, corroborate and collaborate when they get something that seems suspicious. It's certainly helpful.

Q. How difficult is it to guard against phishing attacks in fast-paced, high-pressure jobs?

Johnson: What we found was that if you're in a job with a lot of time pressure, that's going to increase the vulnerability. You might sit down in the morning, you're groggy, and you're like, "I got to go through these 30 emails before this meeting."

Well, in that case, you're not really thinking and asking yourself, "This request I just got in this email, is it legit?" And the next thing you know, you've given somebody your user ID and password.

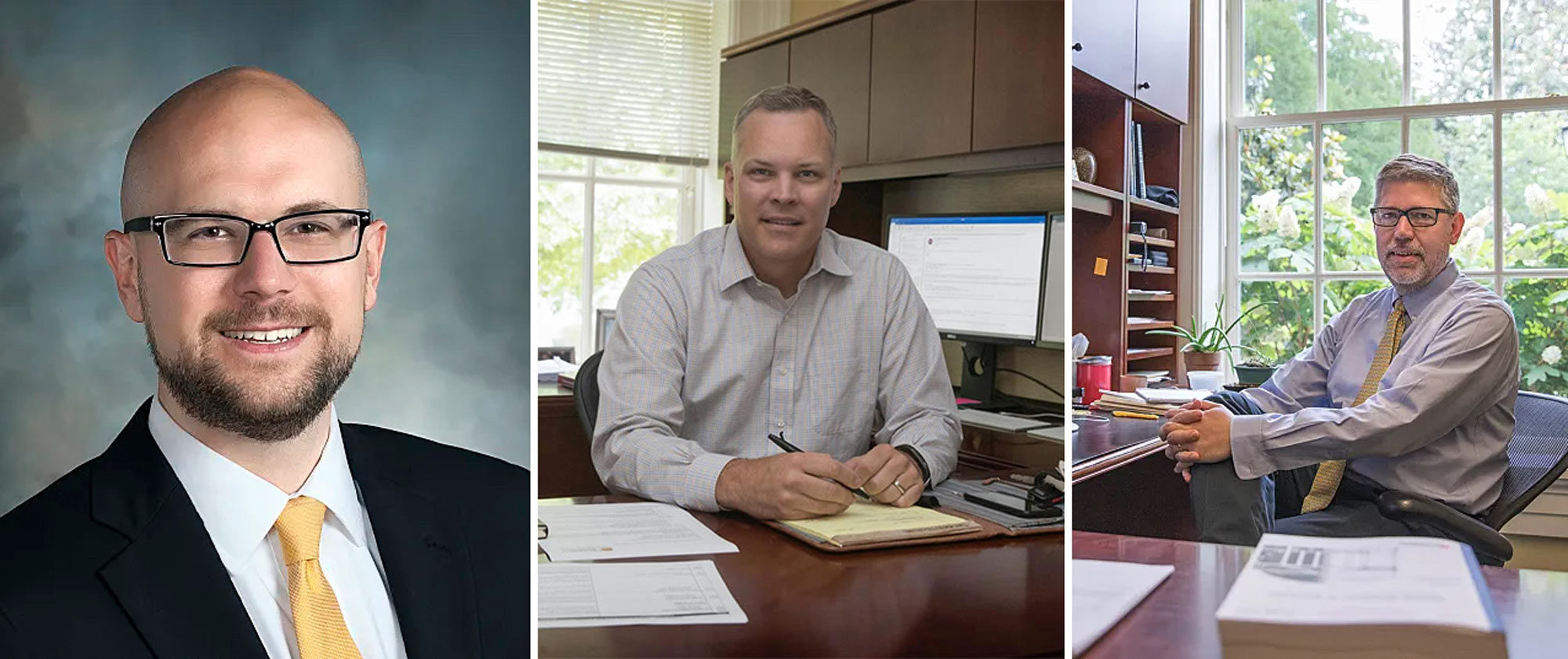

) McIntire professors, from left, Brent Kitchens, Ryan Wright and Steven L. Johnson found that employees with less connection to coworkers are more susceptible to phishing scams. (Contributed photos)

The key is to be more mindful. Just take that pause and say, "Is this really legitimate?" And, if you're really connected in an organization, that's the opportunity to ask your co-worker, "Hey, I got this request. Did you get this email?" Even in severe time pressure, you would feel comfortable taking a moment and checking in with a colleague.

Q. What surprised you most about your findings?

Wright: One of the most surprising findings in this study was that employees that are the heaviest users of the IT help desk are the most vulnerable to social engineered attacks.

You would think that employees that reach out to the IT professionals are more secure. We found the opposite happened. We theorize that employees that are the heavy help-desk users feel a sense of indemnification.

Essentially, they perceive cybersecurity as an external responsibility - specifically, the domain of the IT department. They adopt the belief that should they inadvertently click on a malicious email or engage in potentially insecure activities, the onus is on the IT department to safeguard them, absolving them of any personal accountability.

Johnson: If you have really high trust in technical support, and you got that because you use them a lot, then there's an indemnification that then you feel like, "Hey, if I do something wrong, they're going to bail me out."

While it's good to have a good relationship with tech support, it's an even better thing to have a good relationship with other co-workers who can help you understand how to use the systems to get your job done.

Q. Based on your findings, what recommendations do you have for organizations interested in heightening cybersecurity practices?

Wright: We recommend pivoting the focus of cybersecurity training from individuals to teams. Our findings show that team-based relationships make individuals less susceptible to social engineering attacks.

This principle aligns with longstanding knowledge from organizational behavior studies asserting that team performance significantly impacts overall organizational outcomes. As it turns out, the same holds true for cybersecurity - team dynamics greatly influence an organization's overall cyber resilience.

Kitchens: It's very effective to hear other people's war stories. An implication of our research, and a recommendation that I would make, is to have these group discussions and as an opportunity for people to share what has gone well, what's gone poorly. Like, what they're seeing as the typical kinds of requests they're getting that are clearly not legitimate.

And then maybe also requests that they get that, at first, they thought weren't legitimate and then they found out they were.