A decade-long analysis of nearly 1,500 supernovae sheds new light on the mysterious dark energy that makes up around 70 per cent of the universe.

Results from the Dark Energy Survey (DES) are consistent with the standard cosmological model of a universe that is expanding at an accelerating rate, but they hint at the exciting possibility that the density of dark energy may have varied over time.

If this is the case, it would change our current understanding of this mysterious force and require more complex models to understand how the universe works.

The results were announced today [8 January 2024] at the 243rd American Astronomical Society (AAS) meeting in New Orleans.

Dark energy was first discovered in 1998 when astronomers observed specific kinds of exploding stars, called type Ia (read "type one-A") supernovae. They made the Nobel-prize-winning discovery that the universe's expansion rate is increasing over time. This was unexpected, as conventional theories suggested that gravity should be slowing down the expansion. While matter (including dark matter) pulls other matter together through gravity, dark energy has a repulsive effect, pushing matter away, causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate.

"Twenty-five years after we first detected that it must exist, we still know very little about dark energy," says Dr Philip Wiseman from the University of Southampton, who presented the results at the AAS meeting. "That's part of what makes it exciting. All the data up until now have been consistent with dark energy being a constant but these results open up the intriguing possibility that the density of dark energy could have changed as the universe expands. Knowing whether it is or isn't a constant will help us to narrow down the theories as to what dark energy might be."

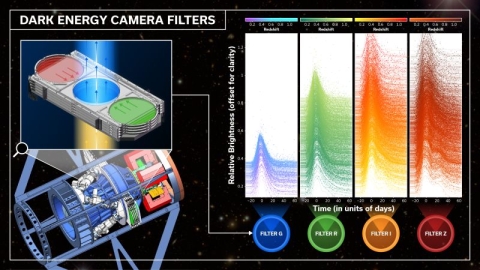

This diagram shows the filter system installed on the Dark Energy Camera used by DES to discover supernovae and monitor their brightness evolution. The method uses an unprecedented four filters: g (bluest filter), r, i, and z (reddest filter). Credit: DES

The Dark Energy Survey is an international collaboration comprising more than 400 scientists from institutions around the world, including the University of Portsmouth, the University of Southampton and the University of Surrey in the UK. DES has mapped an area of almost one-eighth of the entire sky using a Dark Energy Camera, capturing data from 758 nights over six years.

With these data, researchers used type Ia supernovae to measure distances far into the universe. This is the same technique used to detect the existence of dark energy back in 1998, but with a much larger, higher quality sample. Using pioneering new techniques, including machine learning and photometry with four filters, the team have analysed 20 times more data, over a wider range of distances.

If dark energy is constant - which means it doesn't dilute as the universe expands, 'w' (the parameter representing dark energy) should be equal to -1. Tantalisingly, the results of the Dark Energy Survey (DES) found w = -0.80.

Dr Or Graur, Associate Professor of Astrophysics at the University of Portsmouth's Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation, said: "At first sight, this is not the minus one that we expected, but our result is still consistent with that value within the margin of uncertainty. That means that we cannot rule out the standard cosmological model of the universe. At the same time, it shows how, the larger our datasets, the more we narrow down that margin of uncertainty, leaving less and less wiggle room. If a future, larger survey significantly agrees with our result rather than with -1, that would point to exciting, exotic new physics."

DES found several thousand supernovae and ultimately used 1,499 type Ia supernovae with high-quality data, making it the largest, deepest supernova sample from a single telescope ever compiled.

Researchers from the universities of Portsmouth and Southampton played a key role in identifying these type Ia supernovae and finding the galaxies in which each one exploded. This allows researchers to measure the speed at which the galaxy is receding and make subtle corrections to these measures, offering greater accuracy.

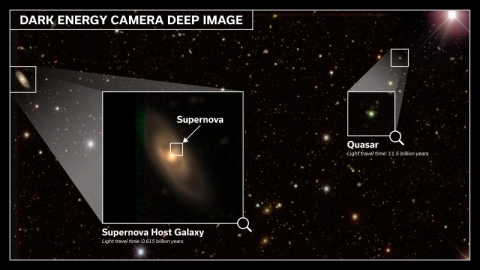

An example of a supernova discovered by the Dark Energy Survey within the field covered by one of the individual detectors in the Dark Energy Camera. The supernova exploded in a spiral galaxy with redshift = 0.04528, which corresponds to a light-travel time of about 0.6 billion years. In comparison, the quasar at the right has a redshift of 3.979 and a light-travel time of 11.5 billion years. Credit: DES collaboration

The DES offers the greatest insight to date on the nature of dark energy, but future projects aim to go even further.

The TiDES experiment is part of a European-led consortium called 4MOST which also involves the universities of Southampton, Portsmouth and Surrey, the three universities working together to lead the Space South Central regional cluster. TiDES will use the Vera Rubin Observatory's Legacy Survey of Space and Time to measure tens of thousands of supernovae.

Bob Nichol, Professor of Astrophysics at the University of Surrey, says "The Vera Rubin Observatory will revolutionise all sorts of different areas of astronomy. It will detect millions of new supernovae, allowing us to pick the very best ones and still have tens of thousands to study.

"This should allow us to definitively tell if dark energy is constant or not. Even so, once we uncover this piece of the puzzle, there will still be much about dark energy to discover, including a compelling theory for its very existence!"

DES was primarily funded by the US Department of Energy and National Science Foundation with some funding provided by the UKRI Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC).