Right now, the world is subject to multiple challenges, including climate change, food and energy security, and environmental degradation.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which came to life in 2015, were intended to guide efforts to reduce poverty and inequalities, and improve wellbeing by 2030, while protecting the environment. All United Nations member states have explicitly committed to achieving them.

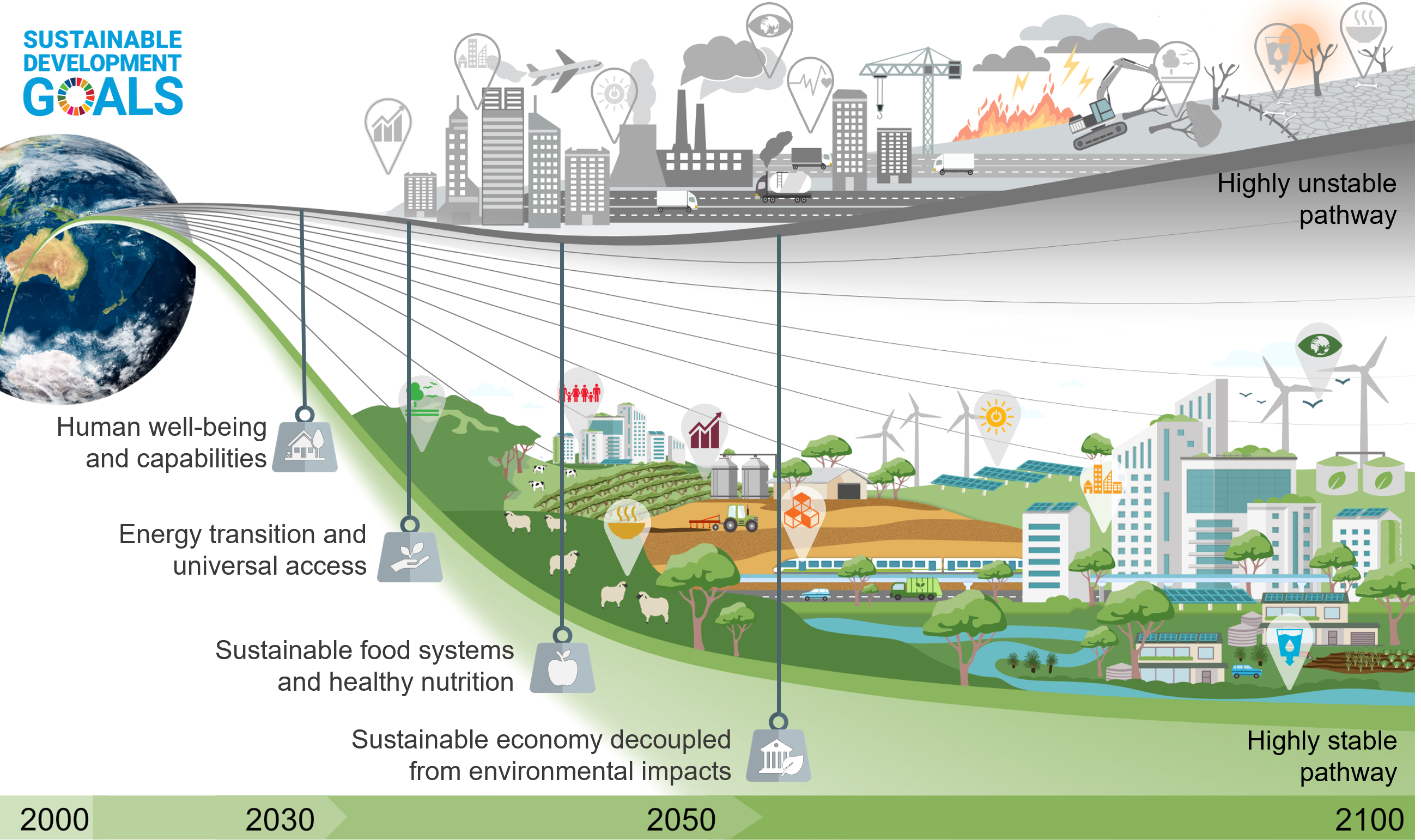

A comprehensive assessment of the SDGs led by researchers from Deakin University has found while measurable progress towards the 2030 SDG targets may be limited, strong immediate action to promote sustainable human and economic development is essential for better outcomes later on, by 2050 or even 2100. The research, published this month in the journal One Earth, identified the changes needed to accelerate longer-term progress towards a better future beyond 2030.

Using a global model that connects key interactions between people, the economy and the environment, the team showed that by following a greener path we can achieve ambitious 2050 and 2100 targets.

However, in order to get there, the team found that aggressive early action was required in four key areas: improving human wellbeing and development, adoption of healthy and sustainable diets, clean and accessible energy, and economic growth but without the environmental impacts. The researchers call this the Green Recovery pathway.

Green Recovery involves lower population growth rates, a growing economy, and better access to education.

Dr Enayat A Moallemi, from Deakin's Centre of Integrative Ecology, said a fast transition to renewable energy driven by lower production costs, higher investment, and technology improvements is also essential to a greener, cleaner future.

'Our future-state modelling showed that lower food demand, lower meat consumption and higher agricultural productivity slammed the brakes on deforestation and reduced greenhouse gas emissions,' Dr Moallemi says.

'Together with ambitious climate policies, the environmental and socio-economic benefits became increasingly clear over the longer term.'

The study puts new detail to the effort required and the likely benefits. For example, improving global access to quality education by 10% by 2050 and 40% by 2100 is necessary to create meaningful change in human development and wellbeing across the globe.

This could be achieved through a range of interventions such as improving local access to schools, ending social and legal discrimination to ensure gender equality in accessing school, and shifting mindsets around the role and benefits of inclusive education in less developed regions.

Dr Moallemi said the mounting evidence of limited SDG progress by 2030 required urgent action.

'Our research highlights the benefits of taking immediate action for sustainable longer-term futures, whereas further delays could lead to irreversible impacts,' he says.

'We specify what it would take across key aspects of society and the economy to fundamentally shift from a pretty bad business-as-usual situation to a more sustainable, green pathway over the course of this century.'

Project leader, Alfred Deakin Professor Brett Bryan, says 'our modelling and analysis highlights that changes that might appear to make a limited contribution to the SDGs in the short term are likely to become very important later on, as progress towards sustainability gathers pace after 2030.'

The team notes that although the study takes a global view, working at the local level is where meaningful change can be made.

'Focusing on local grassroots initiatives can better enable us to implement programs and actions that can scale up to global impact,' Prof. Bryan says.

'Turning our attention to community-led, place-specific efforts are often more effective as they are sensitive to local needs and priorities.'