While Aussies tuck into calamari and chips at the beach, Flinders University researchers have taken a look at why the large Dana octopus squid, which can weigh up to 160kg and measure 2.3 metres long, is so popular on sperm whales' menu.

While rarely seen and relatively unknown, the new study of biochemical samples from the Dana octopus squid (Taningia danae) samples found floating in remote South Australian waters explains how these large animals capitalise on their deep-sea diet in the Southern Ocean and nutrient rich Great Australian Bight.

"While the tissues have very low amounts of calories per gram, their sheer size means they actually have more calories than all other fish in the Southern Ocean, aside from toothfishes," says marine biology researcher Bethany Jackel, from the College of Science and Engineering at Flinders University.

"This makes them a great food source for large predators like the sperm whale because, instead of having to hunt lots of smaller fishes or squids to gain calories, they could hunt a single Taningia danae and get the same amount or even more."

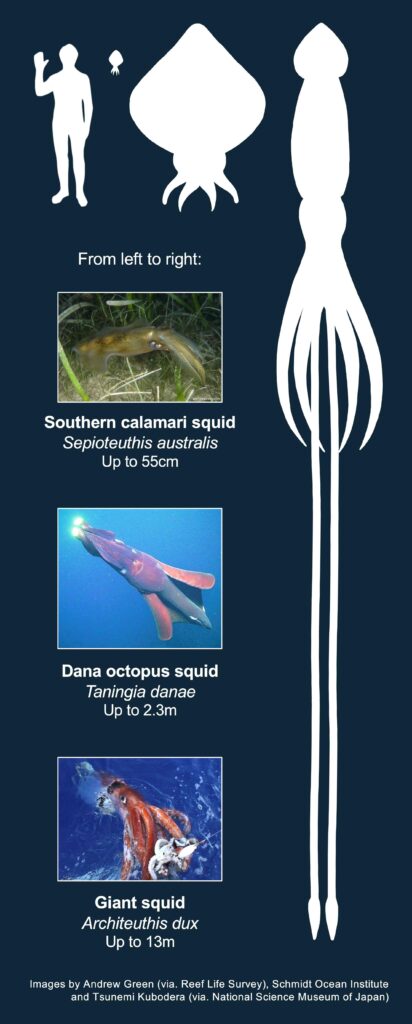

It also explains why the hard beaks of Dana octopus squid are often found in the stomachs of predators like the sperm whale or large sharks and seals. It compares in size to the legendary Giant Squid, which can measure up to 13m long.

Flinders academic Dr Ryan Baring, a coauthor of the new study published in Frontiers in Marine Science, says levels of nitrogen and fatty acids measured in the tissues confirm the octopus squid feed quite high in their food web, probably eating mostly small deep-sea fishes as well as possibly other squid.

"This relatively unknown species is an important part of the food webs of the Southern Ocean and the Great Australian Bight," says Dr Baring.

"They eat deep-sea fishes and squids and in turn become calorie-rich food items for large predators including sperm whales, elephant seals and deep-sea sharks.

"Their movements between the Southern Ocean and the Great Australian Bight might also be an important way for nutrients to move between these two areas, especially from the nutrient-rich Great Australian Bight to the nutrient-poor deep Southern Ocean.

"The Southern Ocean is relatively poor in nutrients compared to the continental shelf in the Great Australian Bight, so maybe they visit to feed on this more nutrient-rich food web."

While rarely found intact, the research team - including other Flinders University experts and the Australian Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry Association - were able to collect and analyse several deceased Taningia danae bodies collected from the eastern Great Australian Bight.

Southern calamari squid, common in human seafood menus, can grow to about 55cm, compared to the octopus which has a body section up to 1.7m.

The study - Towards unlocking the trophic roles of rarely encountered squid: Opportunistic samples of Taningia danae and a Chiroteuthis aff. veranii reveal that the Southern Ocean top predators are nutrient links connecting deep-sea and shelf-slope environments (2023) by Bethany Jackel, Ryan Baring, Michael P Doane, Jessica Henkens, Belinda Martin, Kirsten Rough (Australian Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry Association) and Lauren Meyer - has been published in Frontiers in Marine Science DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1254461 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1254461

Acknowledgements: Funding for this study was acquired by the Ecosystem Resilience Research Group, the Southern Shark Ecology Group and Flinders Accelerator for Microbiome Exploration (FAME) at Flinders University, as well as Australian Research Council DE220101409.