Key Takeaways

- The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument collaboration has publicly released the first 13 months of data from its main survey - a treasure trove that will help other researchers investigate big questions in astrophysics.

- Although DESI's Data Release 1 is only a fraction of what the experiment will capture, the 270-terabyte dataset holds a vast amount of information, including precise distances to millions of galaxies.

- DESI's data release contains more than twice as many unique objects outside our galaxy as in all previous 3D spectroscopic surveys combined.

The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) is mapping millions of celestial objects to better understand dark energy: the mysterious driver of our universe's accelerating expansion. Today, the DESI collaboration released a new collection of data for anyone in the world to investigate. The dataset is the largest of its kind, with information on 18.7 million objects: roughly 4 million stars, 13.1 million galaxies, and 1.6 million quasars (extremely bright but distant objects powered by supermassive black holes at their cores).

While the experiment's main mission is illuminating dark energy, DESI's Data Release 1 (DR1) could yield discoveries in other areas of astrophysics, such as the evolution of galaxies and black holes, the nature of dark matter, and the structure of the Milky Way.

"DR1 already gave the DESI collaboration hints that we might need to rethink our standard model of cosmology," said Stephen Bailey, a scientist who leads data management for DESI and works at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab). "But these world-class datasets are also valuable for the rest of the astronomy community to test a huge wealth of other ideas, and we're excited to see the breadth of research that will come out."

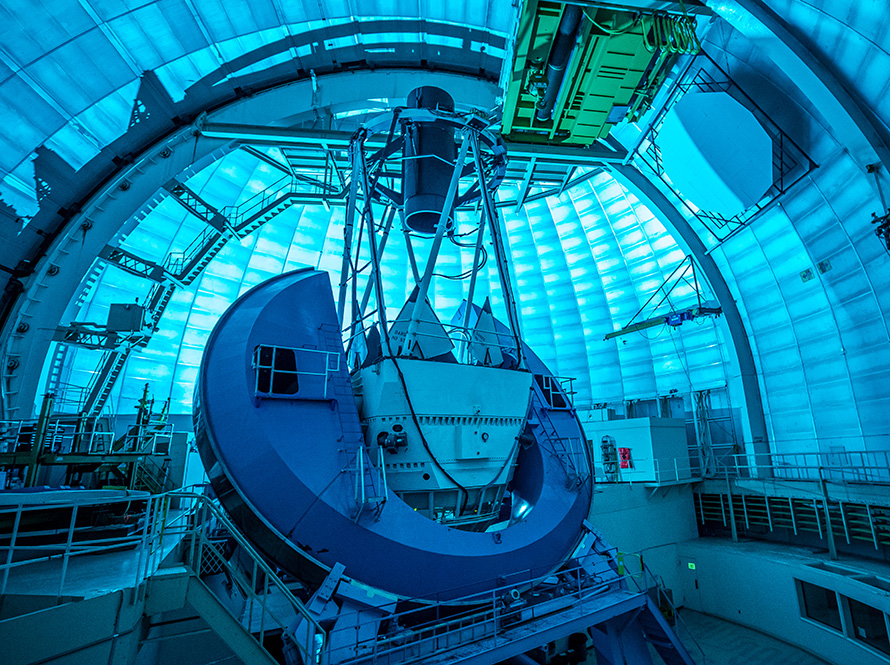

DESI is an international experiment that brings together more than 900 researchers from over 70 institutions. The project is led by Berkeley Lab, and the instrument was constructed and is operated with funding from the DOE Office of Science. DESI is mounted on the U.S. National Science Foundation's Nicholas U. Mayall 4-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory (a program of NSF NOIRLab) in Arizona.

DESI's data release is free and available to access through the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a facility at Berkeley Lab where DESI processes and stores data. Space fans can also explore some of DESI's data through an interactive portal: the Legacy Survey Sky Browser.

The new dataset vastly expands DESI's Early Data Release (EDR), containing roughly 10 times as much data and covering seven times the area of sky. DR1 includes information from the first year of the "main survey" collected between May 2021 and June 2022, as well as from the preceding five-month "survey validation" where researchers tested the experiment.

Objects in DESI's catalog range from nearby stars in our own Milky Way to galaxies billions of light-years away. Because of the time it takes light to travel to Earth, looking out in space is akin to looking back in time. DESI lets us see our universe at different ages, from the present day to 11 billion years ago.

Although DR1 is just a fraction of what DESI will eventually produce, the 270-terabyte dataset represents a staggering amount of information, including precise distances to millions of galaxies. The release contains more than twice as many extragalactic objects (those found outside our galaxy) as have been collected in all previous 3D surveys combined.

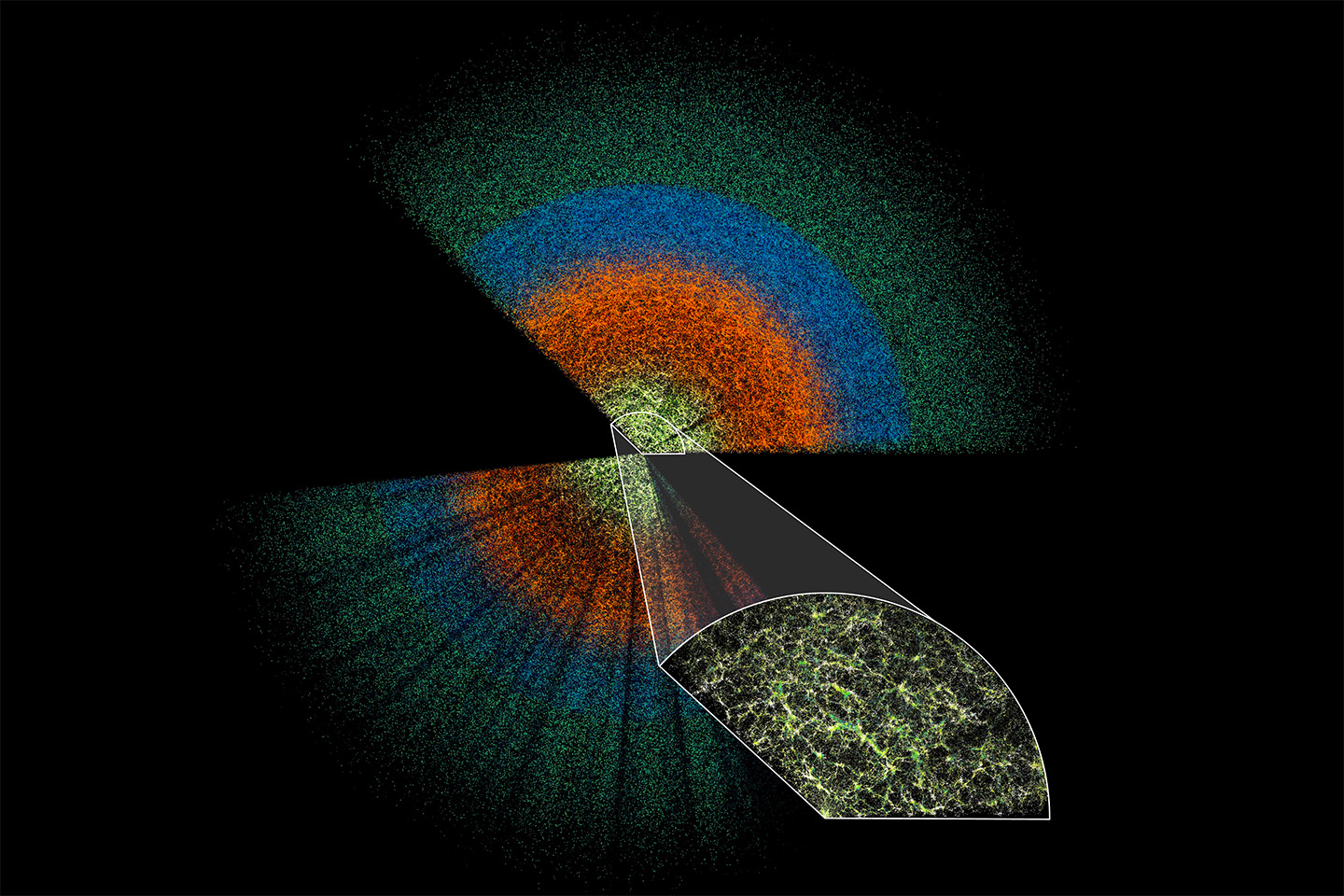

Within its first year of operations, DESI became the single largest spectroscopic redshift survey ever conducted, sometimes capturing data on more than 1 million objects in a single month. For comparison, its predecessor, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), collected light from 9 million unique objects over roughly 25 years of operations. In 2024, DESI researchers used the data in DR1 to create the largest 3D map of our universe to date and make world-leading measurements of dark energy.

"The DESI project has maintained the pace of making 3D maps of the universe that are 10 times larger every decade," said David Schlegel, one of the lead scientists at Berkeley Lab for both DESI and SDSS. "That's our version of Moore's Law for cosmology surveys. The rapid advance is powered by the clever combination of improved instrument designs, technologies, and analysis of ever-fainter galaxies."

Large-scale science for a large-scale audience

DESI collects light from distant galaxies by using 5,000 fiber-optic "eyes." Under clear observing conditions, the instrument can gather a new set of 5,000 objects roughly every 20 minutes, or more than 100,000 galaxies in one night. "DESI is unlike any other machine in terms of its ability to observe independent objects simultaneously," said John Moustakas, a professor of physics at Siena College and co-lead of DR1.

The instrument separates the light from each galaxy into its spectrum of colors. This lets researchers determine how much the light has been "redshifted," or stretched toward the red end of the spectrum by the universe's expansion. Measuring the redshift of light from a distant object tells scientists how far away it is, meaning DESI can map the cosmos in three dimensions and reconstruct a detailed history of cosmic growth.

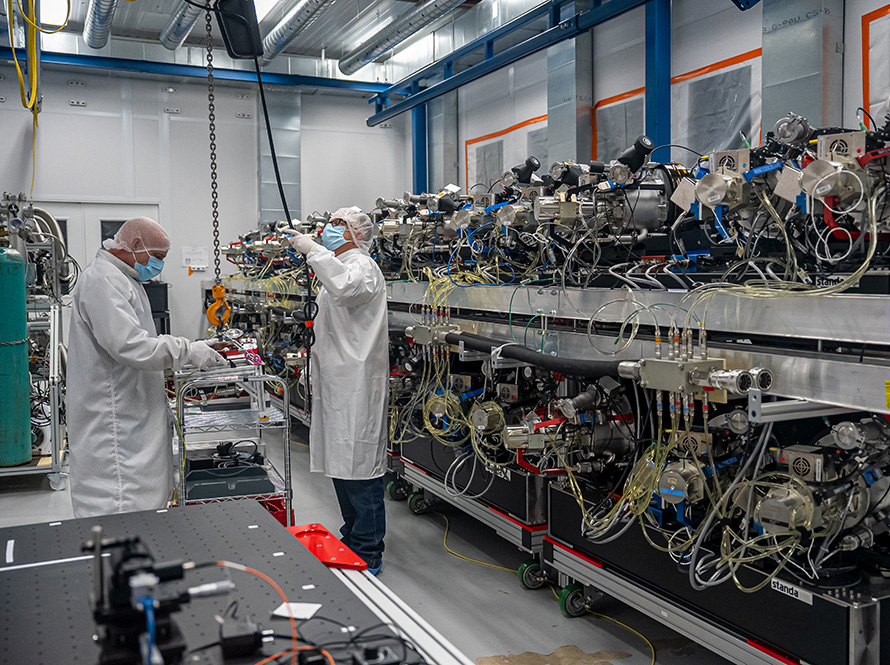

Every night, the images taken by DESI are automatically transferred to supercomputers at NERSC. The facility analyzes the data and sends them back to the researchers - a process they're proud to advertise as "redshifts before breakfast." This data transfer takes place via ESnet, the DOE's dedicated high-speed network for science. The approach represents a new way of doing research where experimental facilities and data analysis are tightly coupled. This ecosystem forms an integrated research infrastructure that drastically accelerates the pace of science.

"For this data release, we made it so DESI could run on our most advanced supercomputer, Perlmutter," said Daniel Margala, a scientific data architect at NERSC and part of the team that supports the DESI data processing. The transition to Perlmutter lets researchers take advantage of the supercomputer's powerful GPUs (graphics processing units), processing the data nearly 40 times faster than was possible on previous NERSC systems. "What would have taken months on Cori [a prior-generation supercomputer] takes only weeks on Perlmutter."

Even though they analyze data every night, researchers are always making improvements to their code to get the most possible information out of the light they collect. Once they hit a milestone, like collecting data for one year, they reprocess the full dataset with the best version of the code. It took about a month to crunch the DR1 dataset on Perlmutter.

That speed will be important as DESI collects even more data. The project is currently in its fourth of five years of data collection and aims to record spectra for more than 50 million galaxies and quasars before it ends.

Collaborators within DESI hope the experiment's data will benefit researchers and enable those without access to large telescopes to advance their work. A major component of the data release is documentation to support other scientists, even those unfamiliar with the project, in understanding its contents.

"We're still discovering all the things you can do with this dataset, and we want the community to be able to try out all their creative ideas," said Anthony Kremin, a project scientist at Berkeley Lab who co-led processing of the new data release. "There are endless kinds of interesting science you can do when you combine our data with outside information."

The DESI DR1 paper is available on the DESI Data website and will be posted on the online repository, arXiv. Videos discussing the data release are available on the DESI YouTube channel. Members of the collaboration presented the data release alongside DESI's newest dark energy analysis (which uses three years of data) in talks today at the American Physical Society's Global Physics Summit in Anaheim, California.

DESI is supported by the DOE Office of Science and by the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science national user facility. Additional support for DESI is provided by the U.S. National Science Foundation; the Science and Technology Facilities Council of the United Kingdom; the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation; the Heising-Simons Foundation; the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA); the National Council of Humanities, Sciences, and Technologies of Mexico; the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain; and by the DESI member institutions.

The DESI collaboration is honored to be permitted to conduct scientific research on I'oligam Du'ag (Kitt Peak), a mountain with particular significance to the Tohono O'odham Nation.