An international team of scientists from UCL, the Swedish Museum of Natural History, the University of Florence and Natural History Museum have found a remarkable type of fossilization that has remained almost entirely overlooked until now.

The fossils are microscopic imprints, or "ghosts", of single-celled plankton, called coccolithophores, that lived in the seas millions of years ago, and their discovery is changing our understanding of how plankton in the oceans are affected by climate change.

Coccolithophores are important in today's oceans, providing much of the oxygen we breathe, supporting marine food webs, and locking carbon away in seafloor sediments. They are a type of microscopic plankton that surround their cells with hard calcareous plates, called coccoliths, and these are what normally fossilize in rocks.

Declines in the abundance of these fossils have been documented from multiple past global warming events, suggesting that these plankton were severely affected by climate change and ocean acidification.

However, a study published today in the journal Science presents new global records of abundant ghost fossils from three Jurassic and Cretaceous warming events (94, 120 and 183 million years ago), suggesting that coccolithophores were more resilient to past climate change than was previously thought.

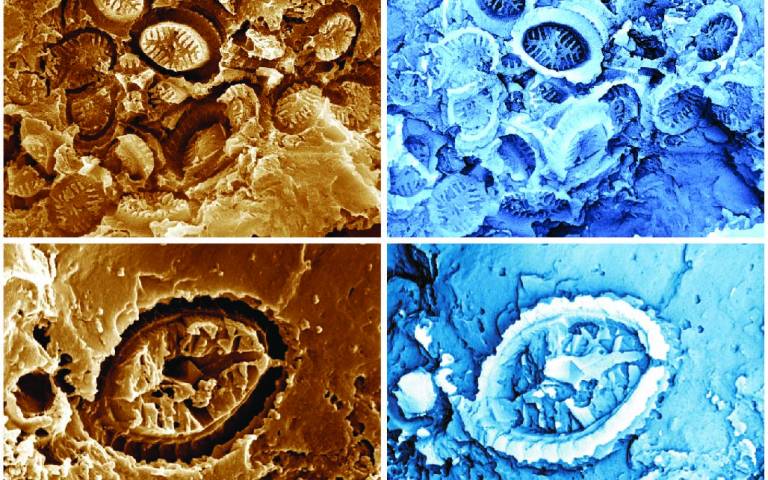

Co-author Professor Paul Bown (UCL Earth Sciences) said: "The preservation of these ghost nannofossils is truly remarkable. The ghost fossils are extremely small ‒ their length is approximately five thousandths of a millimetre, 15 times narrower than the width of a human hair! ‒ but the detail of the original plates is still perfectly visible, pressed into the surfaces of ancient organic matter, even though the plates themselves have dissolved away".

"The discovery of these beautiful ghost fossils was completely unexpected", said Dr Sam Slater from the Swedish Museum of Natural History. "We initially found them preserved on the surfaces of fossilized pollen, and it quickly became apparent that they were abundant during intervals where normal coccolithophore fossils were rare or absent - this was a total surprise!"

Despite their microscopic size, coccolithophores can be hugely abundant in the present ocean, being visible from space as cloud-like blooms. After death, their calcareous exoskeletons sink to the seafloor, accumulating in vast numbers, forming rocks such as chalk.

The ghost fossils formed while the sediments at the seafloor were being buried and turned into rock. As more mud was gradually deposited on top, the resulting pressure squashed the coccolith plates and other organic remains together, and the hard coccoliths were pressed into the surfaces of pollen, spores and other soft organic matter. Later, acidic waters within spaces in the rock dissolved away the coccoliths, leaving behind just their impressions - the ghosts.