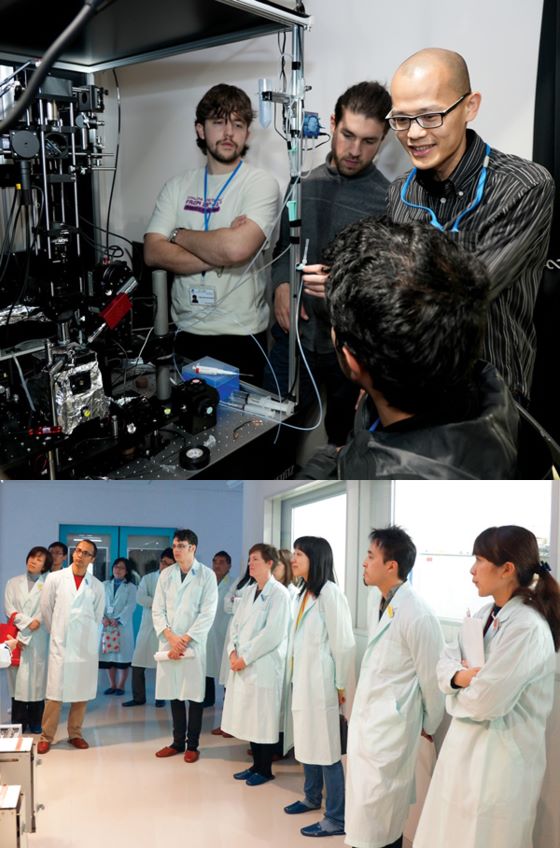

Students from a variety of research fields and countries interact during a RIKEN summer school. © 2024 RIKEN

I'm a strong believer that diversity is good for science. And I'm convinced that one big benefit of increasing the diversity among researchers at RIKEN will be enhancing the quality of science. That's because everyone brings a unique perspective to their research. The more varied the make-up of a team is in terms of gender, age, country and background, the greater the likelihood of coming up with innovative, 'outside of the box' approaches to solving challenging problems. And so, promoting this kind of diversity will have the flow-on benefit of enhancing RIKEN's excellent research.

We are currently focusing on three main diversity goals at RIKEN: ensuring a wider spread of nationalities among researchers; increasing the proportion of women researchers (especially principal investigators); and helping young researchers launch their careers.

An international blend

One strength of RIKEN's current effort is in attracting and supporting researchers from other countries. It is estimated that 27% of RIKEN researchers are from overseas. That's impressive when you realize that non-Japanese nationals account for only about 3% of Japan's general population.

I think it's a reflection of the strong support we provide to non-Japanese researchers, such as help with finding accommodation (including on-campus housing), Japanese language classes, assistance with paperwork, medical assistance and counseling. We also have programs to attract and hire young international researchers.

But there's still room for improvement in this area. We're working on achieving an even wider mix in terms of cultural perspective. Currently, many of our overseas researchers come from other places in East Asia, a fact that is understandable considering the geographical and cultural proximity. In future, we'd like to attract more researchers from further afield, such as Africa, South Asia, South America and Europe.

RIKEN attracts the attention of a variety of researchers, from those studying motor control with Terufumi Fujiwara (top, at right), to those who come to see its world-class labs (bottom). © 2024 RIKEN

Boosting women scientists

We are not so strong in achieving gender balance. We still have a lot of catching up to do compared with our counterparts in some other countries. Currently, only about 10% of our laboratory leaders-known as principal investigators-are women. That low proportion is probably a reflection of a longtime dominance of male researchers in Japan. In 2018, only 16.56% of the research workforce in Japan was made up of women, compared to 33.3% globally according to the UNESCO Science Report 2021.

But RIKEN has a long and proud history dating back to the early 20th century of showing that it is possible to challenge social norms and provide a supportive environment for women researchers (see box). We're intent on building on this legacy and leading the way in Japan in terms of gender equality. For example, we have introduced women-only appointments for some positions. In fact, we've named one of our programs after a former RIKEN chief scientist, and the third woman in Japan to receive a PhD, Sechi Kato. Launched in 2018, the Sechi Kato Program provides funding and support to recruit women into early career principal investigator roles at RIKEN.

I think it's especially important to encourage women in areas that have been dominated by men, such as physics, engineering, quantum computing and artificial intelligence. Our aim is to set up a virtuous cycle, so that, as more women researchers join RIKEN, they in turn will inspire other women to pursue ambitious careers in science.

Overcoming unconscious bias

It is vital to proactively promote diversity due to the phenomenon of unconscious bias. My background is in psychology and one of the things that psychology teaches us is the pervasive nature of unconscious bias-when social stereotypes are applied to people that the individual applying the stereotype has formed outside of their own conscious awareness. We all have unconscious bias in some measure, and it's pernicious because we are usually unaware of it.

For example, you might think that having pursued a career as a woman in science for decades, I would be very conscious of gender inequality. But I had my eyes opened when I came to RIKEN.

In one of my previous posts at a Japanese university, I was a member of a department that had about 100 faculty members, of which only a couple were women. At the time, it didn't strike me a strange at all; I just accepted the situation as normal.

But after joining RIKEN with its emphasis on diversity, I realized in retrospect that it was perhaps an odd environment for me to have been working in. And so, it's crucial to create a culture where diversity is encouraged and celebrated.

Launch pad for new careers

One of RIKEN's four missions during the time span between 2018-2025 is to pioneer innovative programs to support cutting-edge research and the training of junior researchers. In other words, we want to create a nurturing environment that will give young researchers the support they need to kickstart their scientific careers.

This is especially important in Japan. Social expectations here sometimes place young researchers in the shadow of senior scientists, blocks their opportunities to develop autonomy and the independence they need to forge their own paths isn't built in culturally. RIKEN strives to provide the best and most exciting opportunities for junior scientists in the crucially important early stages of their careers.

To help cultivate the next generation of outstanding researchers, we've introduced a variety of short- and long-term programs that cater to researchers at every level: master and doctoral students, postdoctoral researchers, and principal investigators.

Another way that we help early career researchers is by hosting events such as the RIKEN Summer School and Discovery Evenings, which are designed to bring young researchers from different fields and cultures together. We also provide mentorship and career support programs for young researchers. Other ways that we are seeking to provide a supportive environment for everyone is by creating a bilingual work and social environment, offering special leave for family care and providing on-campus childcare at three of our biggest campuses (Wako, Yokohama and Kobe).

As part of the RIKEN Diversity Initiative, which was launched in 2021, we've also launched a dedicated website showcasing the various programs and initiatives underway to promote diversity (https://diversity.riken.jp/en/). It's a good place to discover our programs and stay up to date with the latest initiatives.

While there's much work still to be done in this area, I believe these programs demonstrate that we are serious about promoting diversity at RIKEN. Diversity really is critical, especially in Japan. Historically, Japan has seen less diverse immigration than many countries and the number of young people is dropping rapidly.

Greater diversity benefits everyone and will help to foster new levels of innovation in science and research.

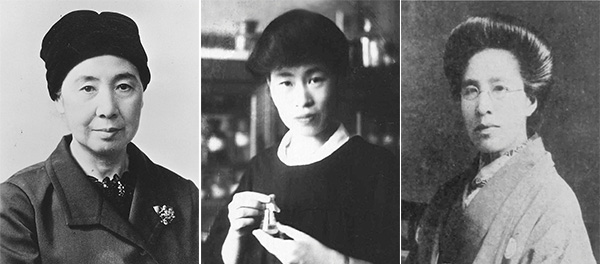

Box: RIKEN's women forebearers

Three names come to mind when we think about women in research at RIKEN: Sechi Kato, Chika Kuroda and Ume Tange. In 1922, Sechi Kato (1893-1989)-a chemist who developed a method for spectrometric analysis of organic materials-was the first woman employed at RIKEN. She wasn't a university graduate at that time, as, in the early 20th century, most women were not allowed to sit university exams in Japan. But Kato went on to become the third woman to receive a Doctor of Science in Japan. In 1951, she became the first woman scientist to lead a RIKEN laboratory as a chief scientist. In 1924, Chika Kuroda (1884-1968), an organic chemist, joined Riko Majima's laboratory at RIKEN as a research scientist, where she investigated natural pigments. In 1916, she had been Japan's first woman to earn a Bachelor of Science. Upon earning a Ph.D. in chemistry from Johns Hopkins University in 1927, Ume Tange (1873-1955) became one of the first Japanese women awarded a doctorate in science. Tange returned to Japan to teach and do further research at RIKEN on vitamins, especially vitamin B2. These three women were trailblazers, and they provide inspirational examples for us today. © 2024 RIKEN