Genetic analysis uncovers 300,000 years of cave occupation by ancient humans and ice age animals

In a landmark study, scientists from Australia, Germany and Russia have used ancient DNA recovered from sediment samples from Denisova Cave in Siberia to reveal a detailed occupational history of this unique site by three distinct groups of ancient humans and a variety of animals over the past 300,000 years.

In the foothills of Russia's Altai Mountains, Denisova Cave is famous as the site where fossil remains of an enigmatic group of archaic humans dubbed the Denisovans were first discovered. It is the only site in the world known to have also been inhabited by their close evolutionary relatives - the Neanderthals - and by early modern humans.

Over the past 40 years, Russian archaeologists have retrieved around a dozen Denisovan and Neanderthal fossils from the cave - including a bone from the daughter of a Neanderthal mother and Denisovan father - but no modern human fossils have been recovered from the deposits. The scarcity of human fossils has thwarted attempts to establish which humans occupied Denisova Cave at various times in the past and which group made the stone tools and other artefacts excavated from the deposits.

In this new study, an interdisciplinary team of scientists assembled by Professor Michael Shunkov from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography (Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences), including geochronologists from the University of Wollongong (UOW), reveals the sequence of human occupation of the cave - as well as other cave-dwelling animals, including bears, hyaenas and wolves - from the genetic analysis of more than 700 sediment samples.

The research, published in Nature on Thursday 24 June (AEST), is the largest analysis ever made of sediment DNA from a single site.

The entrance to Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains in Russia.

The identification of ancient human DNA in 175 sediment samples greatly expands our knowledge of Denisovans and Neanderthals at the site, and also provides the first direct evidence of modern humans at Denisova Cave.

The researchers discovered that Denisovans inhabited the cave, on and off, from 250,000 years ago until 60,000 years ago, and were responsible for the earliest stone tools found at the site.

Neanderthals first appeared about 200,000 years ago, with a particular variety of DNA that was previously unknown, and had disappeared by 40,000 years ago - similar to the time of their disappearance elsewhere in Eurasia.

The ancient DNA of modern humans first shows up in sediments deposited between about 60,000 and 45,000 years ago.

UOW geochronologists Distinguished Professor Richard 'Bert' Roberts, Professor Zenobia Jacobs, Associate Professor Bo Li and PhD student Kieran O'Gorman collected 728 sediment samples in a dense grid from the exposed sediment profiles in the cave.

"The analysis of sediment DNA provides a wonderful opportunity to combine the dates that we previously determined for the deposits in Denisova Cave with molecular evidence for the presence of people and fauna," Professor Roberts said.

"Just collecting hundreds of samples from all three chambers in the cave, and documenting their precise locations, took us more than a week, but we obtained a comprehensive set of samples spanning more than 300,000 years of Siberian history," Professor Jacobs said.

The new study builds on the detailed timeline obtained from optical dating of the Denisova Cave sediments at UOW, published in Nature in 2019.

"The chronology generated previously for the cave sediments allowed us to choose the best places to collect the DNA samples and make the most of the extraordinary insights from sediment DNA," Professor Jacobs said.

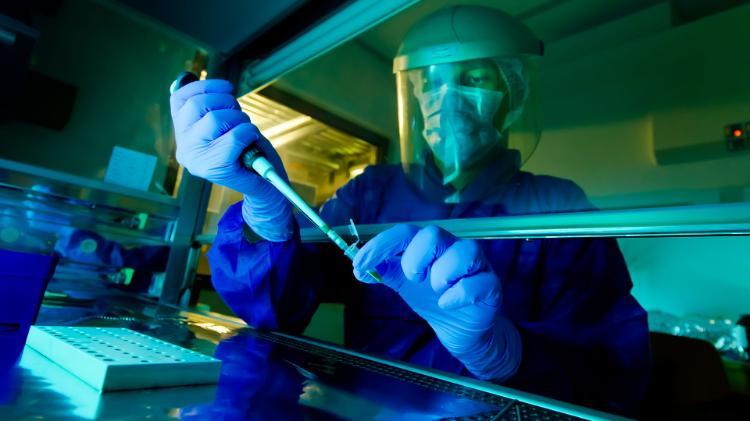

At the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, PhD student Elena Zavala, the study's lead author, extracted and sequenced small traces of ancient human and animal mitochondrial DNA from the huge collection of samples.

"These efforts paid off and we detected the DNA of Denisovans, Neanderthals and ancient modern humans in 24 per cent of the samples," she said.

When matching the DNA profiles with the ages of the layers, the researchers found the first humans to visit the site were Denisovans about 250,000 years ago, followed by Neanderthals about 200,000 years ago. Only Neanderthal DNA was found in sediments deposited between 130,000 and 80,000 years ago. Denisovans who came back after this time carried a different mitochondrial DNA to Denisovans who were there earlier, suggesting a different population had arrived in the region.

Modern human DNA first appears in the Initial Upper Palaeolithic layers, which contained pendants and other ornaments made from animal bones and teeth, mammoth ivory, ostrich eggshell, marble and gemstones. "This provides not only the first evidence of modern humans at the site, but also suggests that they may have brought new technology into the region with them," Ms Zavala said.

The scientists also found animal DNA in nearly all samples, and identified two time periods when changes occurred in both animal and human populations. The first, around 190,000 years ago, coincided with a shift from relatively warm to relatively cold conditions, when hyaena and bear populations changed and Neanderthals first appeared in the cave.

The second major change occurred between 130,000 and 100,000 years ago, along with a shift in climate from relatively cold to relatively warm conditions. During this period, animal populations changed again, Denisovans vanished, and Neanderthals were left as the only human occupants of the cave.

"The coincidence of these population turnovers with climatic transitions between interglacial and glacial periods suggests that environmental factors played a key role in shaping the human and faunal history of this region," Professor Roberts said.

Professor Matthias Meyer, leader of the Advanced DNA Sequencing Techniques group at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and senior author of the new study, said: "Being able to generate such dense genetic data from an archaeological site is like a dream come true. There is so much information hidden in sediments - it will keep us and many other geneticists busy for a lifetime."

about the research

'Pleistocene sediment DNA reveals hominin and faunal turnovers at Denisova Cave', by Elena I. Zavala et al. is published in Nature (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03675-0).

This project was funded by the Max Planck Society, the European Research Council and the Australian Research Council.