In his role at Duke, Ryan Imperio focuses his camera on the eyes of patients, hoping to unlock ways to help them see.

Away from work, Imperio points his camera to the heavens, searching for some of the rarest images human eyes will ever see.

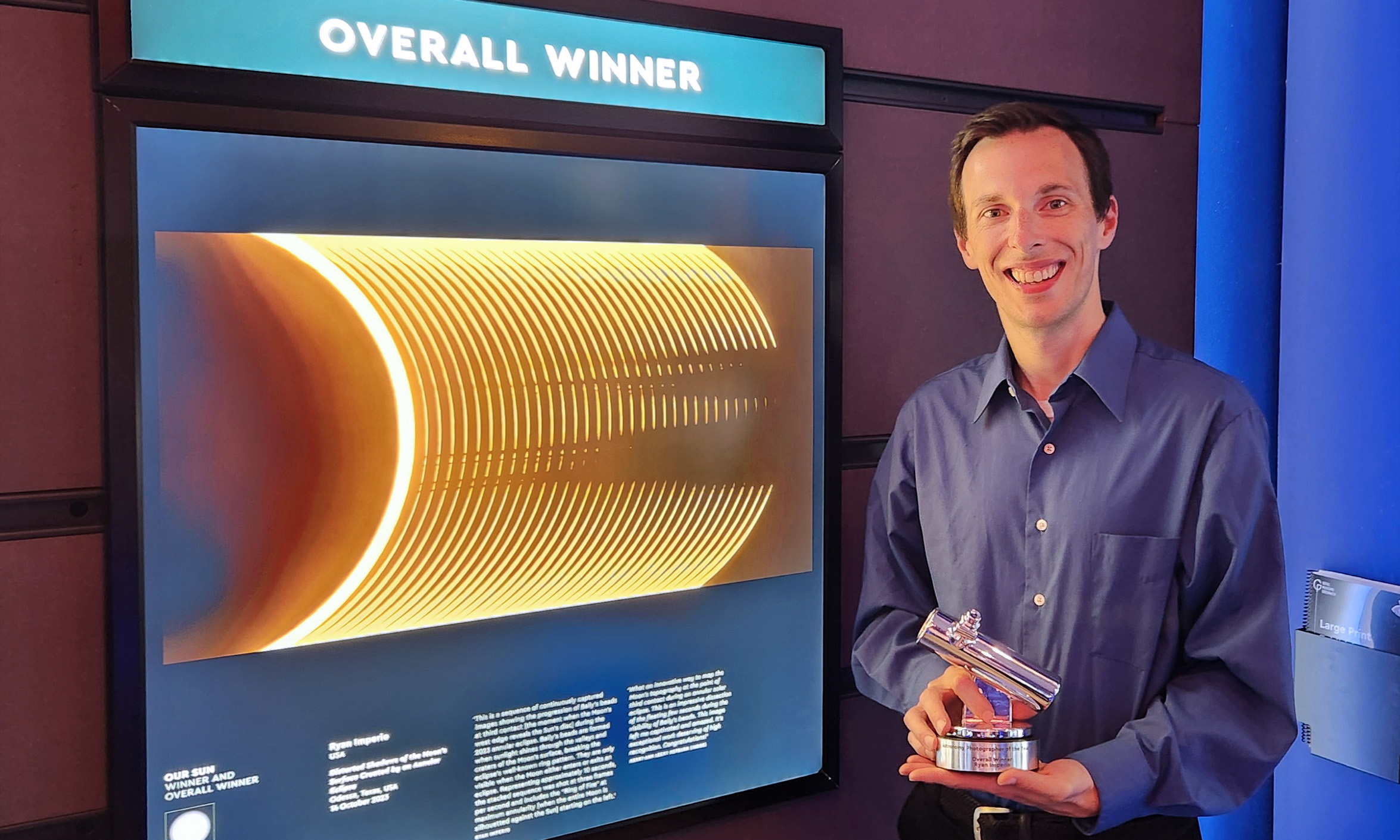

Since 2017, Imperio, 37, a Duke Eye Center Ophthalmic Photographer, has found a creative outlet in astrophotography, the pursuit of capturing images of celestial bodies and events. And this year, Imperio's images of a 2023 eclipse led to the Royal Museums Greenwich in London naming him the 2024 Astronomy Photographer of the Year .

"It still blows my mind," said Imperio, who has worked at Duke since 2013. "The images selected in that contest every year are taken by very talented people. It's very impressive work. I'm thrilled to have my image alongside them."

Working in the lab of Dr. Cynthia Toth , Imperio uses sophisticated cameras to scan patients' retinas, giving researchers valuable images detailing the small structures of the eye.

An ophthalmic photographer since 2010, Imperio said he only picked up photography as a hobby a few years ago.

"I never picked up a camera as a kid or had any interest in taking photos," Imperio said. "People would ask me if I take photos outside of work. I was always like 'No, I just do it for my day job.'"

Imperio began taking nature photos with his smartphone and reading basic composition techniques. In 2017, while on a camping trip to Idaho, he captured images of a solar eclipse with a Nikon D90 camera he bought from a Duke colleague.

"I got some decent images, but I wasn't satisfied," Imperio said. "At that point in time, I wasn't an experienced with astrophotography, or photography in general."

Fascinated by the process and potential of astrophotography, Imperio committed to improving his abilities. There would be other eclipses, and he wanted to be ready.

On clear nights, he traveled to places known for dark skies, such as the Jordan Lake State Recreation Area or Virginia's Staunton River State Park, taking photos of comets, meteor showers and the Milky Way.

In 2023, Imperio chose the annular - or not-quite-total - eclipse on October 14 as his next subject. He traveled to Texas, where the eclipse would be most intense. Finding clear skies in the West Texas town of Odessa, Imperio set his camera - he now used a Nikon D810 - on a tri-pod next to a building to block it from the wind.

"A lot of people shoot an eclipse and get the big ring, and that's basically all they get, or maybe they time lapse through the whole thing," Imperio said. "I wanted to go beyond that."

Using a 600-milimeter telephoto lens and a smartphone app that provided extremely precise timing, Imperio aimed for Baily's beads, a rarely photographed phenomenon occurring during eclipses. It's when light from the sun passes across the rugged landscape of the moon creating shadows visible, for just a moment, to observers on earth.

Calculating when the Baily's beads would happen, Imperio shot a series of 33 images in a span of 10.6 seconds.

When he first looked at the images, he saw where the clean arc of the eclipse was broken by the Baily's beads.

"I knew I got something," Imperio said. "But I didn't know the sequence I had until I got home and actually stacked the images together. That's when I realized what I had."

Once combined, Imperio's image shows the shadows of the lunar surface's mountain peaks gradually appearing as the moon slides in front of the sun.

Each year, thousands of photographers submit images to the Astronomy Photographer of the Year contest organized by the Royal Museums Greenwich in London. The best photos are collected in a commemorative book and one is chosen as the overall winner.

"They're basically the world's best images," Imperio said. "It's a big deal. I've been following it for many years and have taken inspiration from these photos."

Prior to this year, Imperio had never submitted a photo to a contest of this magnitude. But he felt the image sequence captured in Texas, which he titled "Distorted Shadows of the Moon's Surface Created by an Annular Eclipse," was worth entering.

After learning that he'd won the contest, Imperio flew to London in September for the opening of an exhibition of winning photos at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

"The whole experience was absolutely unbelievable," said Imperio, who earned a trophy and a cash prize of roughly $15,000 for the honor. "I couldn't have dreamed this."

His trophy sits on a shelf in his Durham home, not far from the commemorative book with his photo spread across pages 32 and 33.

Imperio now plans to dive deeper into his hobby by using some of his winnings to buy an astro-modified camera that can capture the pastel hues of the Milky Way and fund more trips to places where the dark, clear skies can reveal more wonders.

Send story ideas, shout-outs and photographs through our story idea form