A European team has confirmed the existence of four new exoplanets thanks to the CHEOPS space telescope.

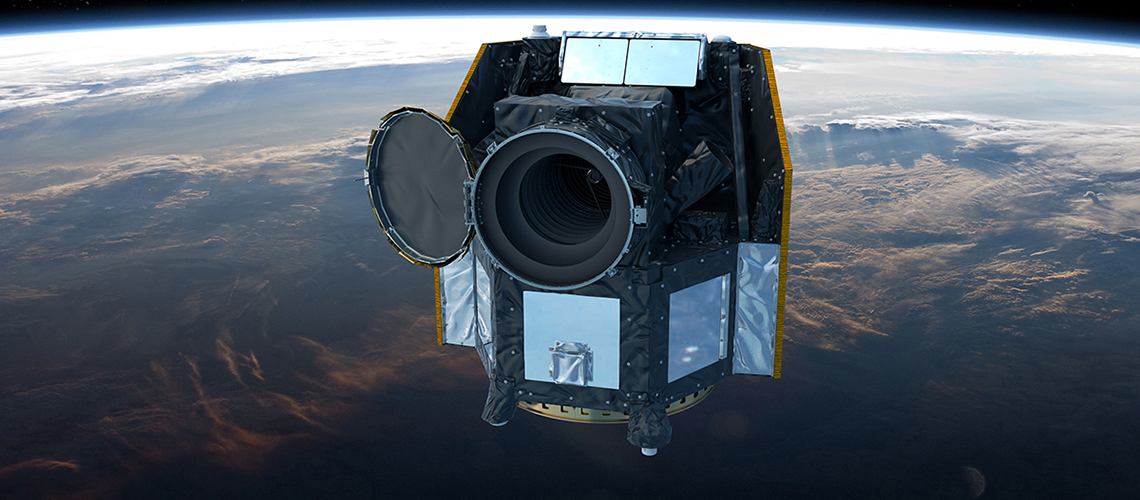

Artistic representation of the CHEOPS space telescope. © ESA / ATG medialab

With the help of the CHEOPS space telescope an international team of European astronomers managed to clearly identify the existence of four new exoplanets. The four mini-Neptunes are smaller and cooler, and more difficult to find than the so-called Hot Jupiter exoplanets which have been found in abundance. Two of the four resulting papers are led by researchers from the University of Bern and the University of Geneva who are also members of the National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS.

CHEOPS is a joint mission by the European Space Agency (ESA) and Switzerland, under the leadership of the University of Bern in collaboration with the University of Geneva. Since its launch in December 2019, the extremely precise measurements of CHEOPS have contributed to several key discoveries in the field of exoplanets.

NCCR PlanetS members Dr. Solène Ulmer-Moll of the Universities of Bern and Geneva, and Dr. Hugh Osborn of the University of Bern, exploited the unique synergy of CHEOPS and the NASA satellite TESS, in order to detect a series of elusive exoplanets. The planets, called TOI 5678 b and HIP 9618 c respectively, are the size of Neptune or slightly smaller with 4.9 and 3.4 Earth radii. The respective papers have just been published in the journals Astronomy & Astrophysics and Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Publishing in the same journals, two other members of the international team, Amy Tuson from the University of Cambridge (UK) and Dr. Zoltán Garai from the ELTE Gothard Astrophysical Observatory (Hungary), used the same technique to identify two similar planets in other systems.

The synergy of two satellites

The CHEOPS satellite observes the luminosity of stars in order to capture the slight dimming that occurs when, and if, an orbiting planet happens to pass in front of its star from our point of view. By searching for these dimming events, called "transits", scientists have been able to discover the majority of the thousands of exoplanets known to orbit stars other than our Sun.

"NASA's TESS satellite excels at detecting the transits of exoplanets, even for the most challenging small planets. However, it changes its field of view every 27 days in order to scan rapidly most of the sky, which prevents it from finding planets on longer orbital periods," explains Hugh Osborn. Still, the TESS satellite was able to observe single transits around the stars TOI 5678 and HIP 9618. When returning to the same field of view after two years, it could again observe similar transits around the same stars. Despite these observations, it was still not possible to conclude unequivocally to the presence of planets around those stars as information was incomplete.

"This is where CHEOPS comes into play: Focusing on a single-star at a time, CHEOPS is a follow-up mission which is perfect to continue observing these stars to find the missing bits of information," complements Solène Ulmer-Moll.

A lengthy game of "hide and seek"

Suspecting the presence of exoplanets, the CHEOPS team designed a method to avoid spending blindly precious observing time in the hope to detect additional transits. They adopted a targeted approach based on the very few clues the transits observed by TESS provided. Based on this, Osborn developed a software which proposes and prioritizes candidate periods for each planet. "We then play a sort of 'hide and seek' game with the planets, using the CHEOPS satellite," as Osborn says.

"We point CHEOPS towards a target at a given time, and depending if we observe a transit or not, we can eliminate some of the possibilities and try again at another time until there is a unique solution for the orbital period." It took five and four attempts respectively for the scientists to clearly confirm the existence of the two exoplanets and determine that TOI 5678 b has a period of 48 days, while HIP 9618 c has a period of 52.5 days.

Ideal targets for the JWST

The story does not end there for the scientists. With the newly found constrained periods, they could turn to ground-based observations using another technique called radial velocity, which enabled the team to determine masses of respectively 20 and 7.5 Earth masses for TOI 5678 b and HIP 9618 c. With both the size and mass of a planet, its density is known, and scientists can get an idea of what it is made off. "For mini-Neptunes however, density is not enough, and there are still a few hypotheses as for the composition of the planets: they could either be rocky planets with a lot of gas, or planets rich in water and with a very steamy atmosphere," explains Ulmer-Moll. "Since the four newly discovered exoplanets are orbiting bright stars, it also makes them targets of prime interest for the mission of the James Webb Space Telescope JWST which might help to solve the riddle of their composition," Ulmer-Moll continues.

Most exoplanets atmospheres observed so far have been from Hot Jupiters, which are very big and hot exoplanets orbiting close to their parent star. "The four new planets which we detected have much more moderate temperatures of 'only' 217 to 277ºC. These temperatures enable clouds and molecules to survive, which would otherwise be destroyed by the intense heat of Hot Jupiters. And they may potentially be detected by the JWST," as Osborn explains. Smaller in size and with a longer orbital period than Hot Jupiters, the four newly detected planets are a first step towards the observation of transiting Earth-like planets.

CHEOPS – in search of potential habitable planets The CHEOPS mission (CHaracterising ExOPlanets Satellite) is the first of ESA's "S-class missions" – small-class missions with an ESA budget much smaller than that of large- and medium-size missions, and a shorter timespan from project inception to launch. CHEOPS is dedicated to characterizing the transits of exoplanets. It measures the changes in the brightness of a star when a planet passes in front of that star. This measured value allows the size of the planet to be derived, and for its density to be determined on the basis of existing data. This provides important information on these planets – for example, whether they are predominantly rocky, are composed of gases, or if they have deep oceans. This, in turn, is an important step in determining whether a planet has conditions that are hospitable to life. CHEOPS was developed as part of a partnership between the European Space Agency (ESA) and Switzerland. Under the leadership of the University of Bern and ESA, a consortium of more than a hundred scientists and engineers from eleven European states was involved in constructing the satellite over five years. CHEOPS began its journey into space on Wednesday, December 18, 2019 on board a Soyuz Fregat rocket from the European spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. Since then, it has been orbiting the Earth on a polar orbit in roughly an hour and a half at an altitude of 700 kilometers following the terminator. |