L'EPFL Spacecraft Team © 2023 EPFL

On January 29, the EPFL Spacecraft Team's onboard computer Bunny was launched in California, USA, hosted on a D-Orbit spacecraft as part of Starlink's 2-6 mission. This is the first time anything made at EPFL has been launched into space since 2009.

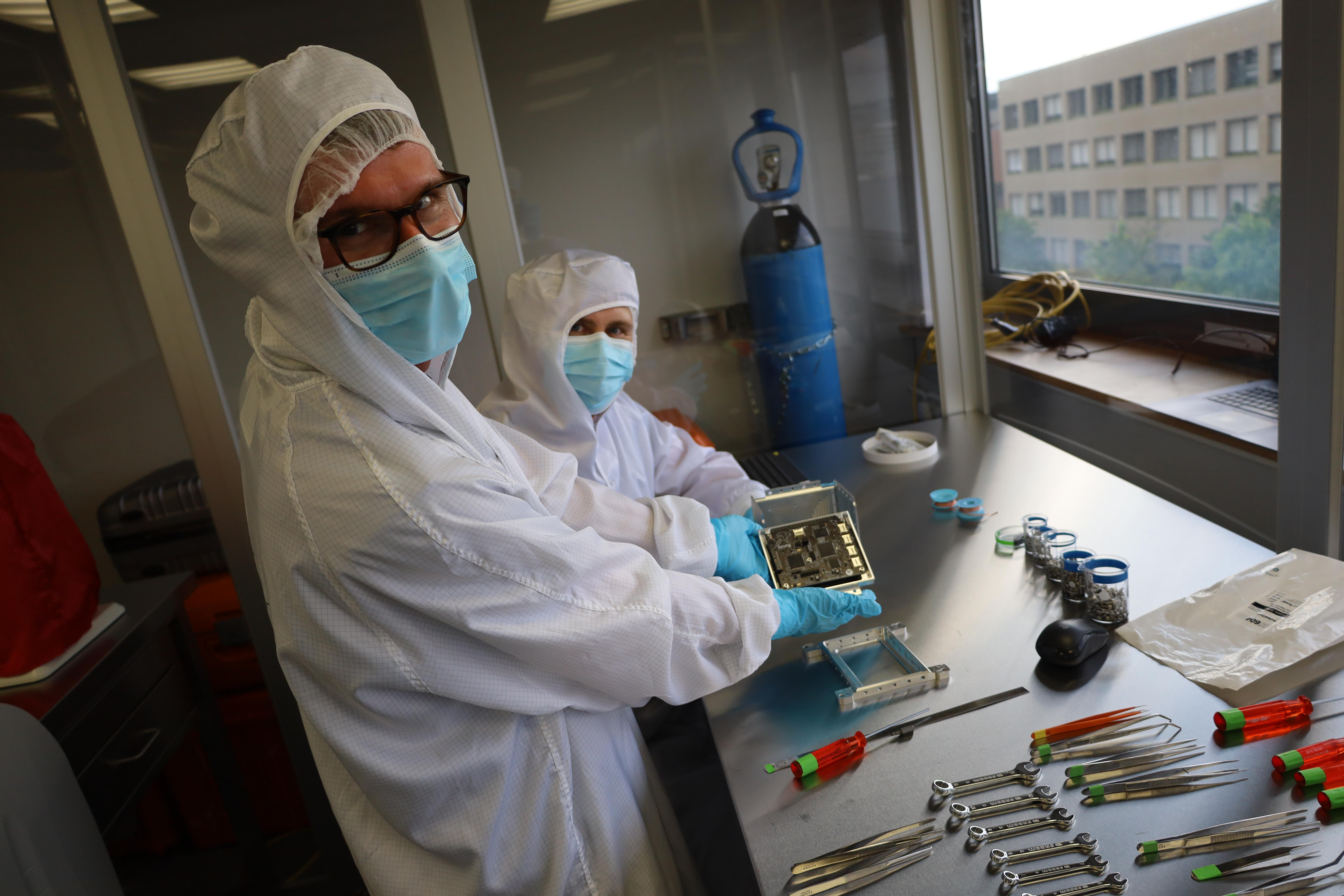

For many, this was just another Starlink launch. For us, this was the return of EPFL to space. A few months ago, we were holding Bunny in our hands, and now it is in orbit. However, the challenge is not over yet. Now we wait for the first contact and hope that our payload survives in the vacuum of space.

Nearly fifteen years after the launch of the SwissCube CubeSat, another piece of EPFL machinery has gone into space: an onboard computer named Bunny, built and designed by the student-run EPFL Spacecraft Team leading the CHESS mission. The aim of the CHESS Mission is to build and launch two CubeSats, miniature satellites in 10x10x30cm cubes, in 2026, and Bunny is a prototype of the onboard computer for that mission.

Initially, the team had been solely focused on that future launch, until Italian aerospace company D-Orbit came to them with an opportunity in April 2022: to fly their computer on an experimental mission inside an ION Satellite Carrier, D-Orbit's orbital transfer vehicle, in January 2023.

"This basically triggered a whole process of trying to rethink our strategy," says Robin Bonny, Vice President of Electronics for the EPFL Spacecraft Team. "At that point, we didn't really know how to go about this process because we weren't that far ahead in the mission. But we always had the onboard computer, the only system that was fully developed by EPFL students at that time. So we thought, let's try to take the design that we have now and get this to fly as soon as possible."

A tight timeline

After D-Orbit presented the opportunity to the Spacecraft Team in April 2022, they had around two months to redo the whole onboard computer in order to have sufficient time to test it and bring it to D-Orbit for integration into their spacecraft by September 2022.

Throughout the summer, the team did full testing procedures. While they understood the computer from an electrical point of view, they also learned how to integrate the electronics they have with something that can actually launch.

"We got this whole list of things that we had to test for and adhere to." says Bonny. "Then the rest of the summer was just testing, testing, testing."

They needed to test for the behavior of Bunny in a vacuum under different temperature ranges, which was something they could do at EPFL in collaboration witheSpace and Space Innovation using their vacuum chamber. To show that Bunny would survive launch with all of the accompanying conditions such as acceleration and vibrations, the team brought the computer to the facilities at the University of Bern, where they could shake the structure of the payload and make sure that nothing came loose. Along with testing the hardware, they also had to develop a robust and bug-free software with no framework.

"I joined the EPFL Spacecraft team to see my code sent to space," says Joaquim Silveira Francolino, a master's student in robotics and the team's Vice President for Software. "The pressure was intense. I found myself more stressed about the tests than my own exams, which were scheduled for the same time."

In September, they went to D-Orbit's facilities in Italy to integrate their piece of hardware and test it with D-Orbit's system. The team also learned about the paperwork side of going into space, completing and submitting all the qualifying documentation.

"Launching something in space is not a simple task," says Prof. Jean-Paul Kneib, Academic Director of the eSpace Center and Principal Investigator for the CHESS Mission. "It requires a lot of commitment and dedication, so these students have to be proud of their achievement!"

Real world experience

Bunny is a 1 Unit payload weighing 0.8 kg that is flying as a hosted payload on the D-Orbit spacecraft, which was on a rideshare Starlink launch along with multiple other Starlink satellites. The specific orbit where the D-Orbit ION spacecraft has gone is in LEO, to a high inclination orbit that is not very typical or highly used, but good for this trial run.

In a few years, a computer similar to this one will be integrated as part of the EPFL Spacecraft Team's CHESS Project to construct and launch two 3U CubeSats (10x10x30cm each) into Low Earth Orbit (LEO), the orbit between Earth and 1000km of altitude. Bunny is intended to be the flight computer of the CHESS CubeSat, responsible of controlling and operating the satellite.In this current mission with D-Orbit, the Spacecraft Team is essentially tricking Bunny into thinking it is in a CubeSat and executing commands. So any failure in this mission will not impact the D-Orbit satellite and will serve as feedback to improve the computer's design.

The future CHESS CubeSats will conduct scientific research such as measuring the chemical composition of Earth's atmosphere. However, this is a long-term project. Already, the team has been working on it for nearly four years and some of the students who worked on it or who are currently working on it won't witness the launch of the two CubeSats. Meanwhile, the Bunny project was done in just a couple of months, allowing a group of over a dozen students to see it through from beginning to end, experiencing the real-world experience of building and qualifying something to be launched into space.

"From an educational perspective, it is really interesting to the average student to actually see this process of having something that's going to fly," says Bonny.

"Integrating the software with the Bunny on the ION was the most stressful task I faced in my academic life," says Silveira Francolino. "The consequences of errors would have been catastrophic for the mission, so there was no room for deviation. But despite the pressure, it was a great experience, and I would recommend it to anyone interested in engineering."

The Bunny mission is also specifically designed to be sustainable, as the ION spacecraft has active deorbiting capabilities that enable it to reduce its altitude and clear the orbit once the mission is complete. Additionally, the satellite is equipped with a drag-sail developed by the German company HPS. This technology ensures that the satellite does not become space debris and pose a threat to other spacecraft, aligning with EPFL's strategy to promote space sustainability.

A future full of launches

"This project marks an important milestone for our association and EPFL", says Belkhiria.

Going forward, the Spacecraft Team hopes to operate a project similar to Bunny each year, so that all student members go through this process of developing and qualifying something for space on a subsystem level within one year.

"We are now aiming at performing multiple in-orbit demonstrations for our components and building a flight heritage before the final launch of CHESS," says Belkhiria.

While the 2009 SwissCube was a single CubeSat, CHESS will be two CubeSats, each three times the size of the SwissCube, and will carry high-grade scientific instruments into space for research. Regularly launching their technology on hosted payloads de-risks that final project, so that when the CHESS mission launches, it will be with flight-proven components. This is crucial as it will carry science payloads that cost over CHF 2 million.

"It seems like a logical progression that the SwissCube was more than 10 years and now we are leveraging this heritage and saying that we as a team of students want to demonstrate that we can go up in complexity," says Bonny.