UdeM guest researcher Claudine Gravel-Miguel working at the site of Arma Veirana in Liguria, Italy, in 2018.

Credit: David Strait

The baby girl was born roughly 10,000 years ago, after the end of the last Ice Age in what is now Liguria, northwestern Italy, but didn't survive more than two months. After she died, she was given a proper burial honouring her as a fully fledged person in her society - a remarkable testament to female equality in Mesolithic times.

That's the conclusion drawn today by a team of archeologists including Université de Montréal's Julien Riel-Salvatore and Claudine Gravel-Miguel, UdeM doctoral student Geneviève Pothier Bouchard and scientists in the U.S., Italy and Germany, in a study led by researchers at the University of Colorado and the University of Genoa, and published in Nature Scientific Reports.

Because the sex of infant skeletons is usually difficult to determine, the team's multidisciplinary analysis is unique, the scientists say: it reveals the oldest definitive instance of a burial of an infant girl ever documented in Europe, and the discovery opens a window into gender and inclusiveness in prehistory, say the scientists, who have nicknamed the girl 'Neve.'

"The way prehistoric people buried their dead gives us insights into how they thought about themselves and their universe," said Riel-Salvatore, a co-author of the study, who helped excavate the archeological site called Arma Veirana, a cave in the Ligurian pre-Alps, where the burial was discovered in 2017.

"Buried children, especially, provide a unique window into the age at which people in the past were considered full members of their societies. This discovery shows that in this Mesolithic group, even newborn girls were treated with the consideration afforded other people of their group."

Added Gravel-Miguel: "While archaeologists of prehistory usually deal with material remains that have accumulated over long time periods, burials provide very rare snapshots of the life of a few individuals, which is priceless to understand how they lived and how they perceived death."

Tools and remnants of meals

With a wife-and-husband team of U Colorado anthropologists - Jamie Hodgkins and Caley Orr - Riel-Salvatore and his colleagues at UdeM and other universities - Arizona State, Washington (in St. Louis, Miss.), Genoa, Bologna, Ferrara and Tübingen, initially uncovered tools and remnants of meals of wild boar and elk left by Neanderthals more than 50,000 years ago.

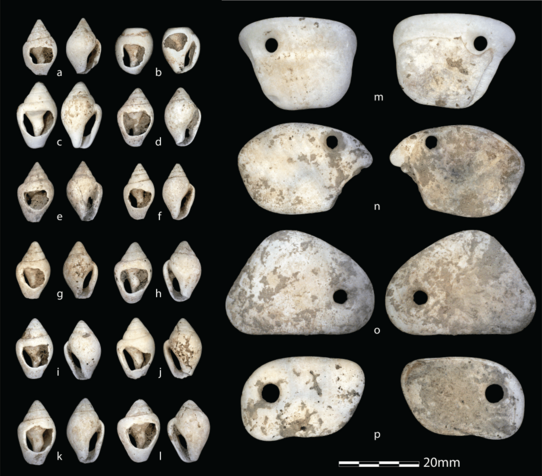

Exploring deeper into the cave where the layers were younger, they found pierced shell beads and remains of a tiny cranium. Through a process of studying its proteins, called proteomic analysis, Pothier Bouchard was able to confirm that the cranium that she had helped unearth was human. Further analysis gave more detail: baby Neve was about six weeks old when she died and had been stressed in the womb, twice interrupting the growth of her teeth.

But it was the discovery of the burial beads - more than 60 in all - along with four pendants and an eagle-owl talon, that particularly excited the researchers. They showed that Neve had been laid to rest with ritual and seeming equality with the hunter-gatherer adults. And the beads weren't new; they'd been worn by others before being sewn onto her clothing, suggesting a direct connection between the living and the dead.

"The fact those beads had been used before implies that Neve had links to the rest of her society and reinforces that she was considered a full-blown person in spite of her young age," said Riel-Salvatore.

About this study

"An infant burial from Arma Veirana in northwestern Italy provides insights into funerary practices and female personhood in early Mesolithic Europe," by Jamie M. Hodgkins et al., was published Dec. 14, 2021 in Nature Scientific Reports.