From dust-like orchid seeds to the massive double coconuts, the variation in seed size is one of nature's most striking features. Large seeds, such as those from oak trees, contain a wealth of resources essential for starting their growth. However, this abundance also makes them appealing targets for animals looking for a convenient snack. But what happens when animals eat part of the seed? Does losing some of their nutrient reserves affect the seed's chances of survival?

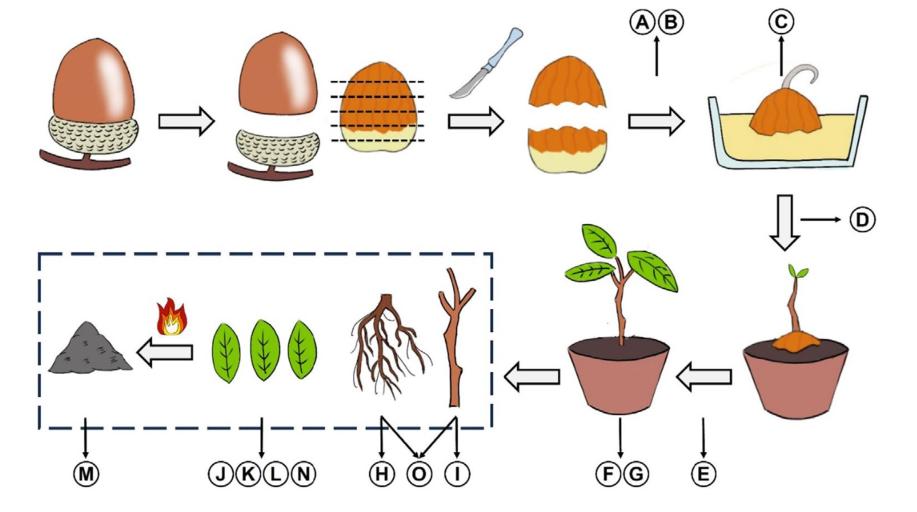

Researchers from the Wuhan Botanical Garden of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK, collected acorns from 20 Fagaceae species in the UK, Spain, and China during 2020 and 2021. They simulated the effects of animal feeding by carefully removing up to 96% of the acorns' nutrient reserves without harming the embryo. The affected seeds were then planted, and their development was monitored from germination to seedling growth. This study was published in the Journal of Ecology.

The researchers found that partial granivory did not significantly affect seed germination. Even when a large portion of the cotyledons was removed, many seeds still germinated successfully. This suggests that seeds contain more nutrients than just those required for germination, showing considerable resilience to partial consumption.

As for seedling growth, it was a different story. As the level of granivory increases, the seedlings have a harder time emerging and establishing. These seedlings struggle to grow with fewer and smaller leaves. They must invest the limited resources in photosynthesis by expanding leaf area as much as possible, thus compromising leaf mechanical defenses. This strategy, although clever, comes with a trade-off: thinner leaves become more vulnerable to herbivores.

Moreover, the size of the seed played a role. Large seeds have evolved their size not only to provide extra resources for seedling growth but also as a defense mechanism. By tolerating partial predation, these seeds can survive and germinate and still benefit from dispersal by animals. Interestingly, the larger the seed, the more likely it is to survive partial consumption. This makes large seed size an effective adaptation for balancing the competing demands of dispersal and predation.

This study sheds light on the relationship between seed size and defense against granivory. It shows that large seeds in the Fagaceae family have a strategy that tolerates partial consumption. Even partially damaged seeds still have a chance to germinate and grow, although the seedlings may face challenges. The study provides insights into the implications for forestry and conservation practices.

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Future Leader Fellowship in Plant and Fungal Science from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research MISTRA (Project BioPath), the Kew Foundation, and the CAS President's International Fellowship Initiative.

Flowchart of the study design: An acorn is separated from its cupule and pericarp, and then artificially deprived of varying amounts of nutrient reserves. The embryo and its remaining seed reserve are planted, and seed germination and seedling growth are monitored. Organs of the seedling are weighed or burned for measuring biomass allocation (Image by CHEN Sichong)