AUSTIN, Texas - In a research analysis to be published Friday in Science, scholars contend that a new federal water rule enacted in 2020 does not adequately account for transboundary pollution across state lines.

One of the government's rationales for enacting the new rule, which removed millions of acres of wetlands and millions of miles of streams from federal protection, was an assumption that states would fill gaps in federal oversight. The research analysis, co-authored by Sheila Olmstead of the LBJ School of Public Affairs at The University of Texas at Austin, suggests this may not occur.

In late March, President Joe Biden proposed a $111 billion investment in water infrastructure. He said his administration will also modernize regulatory review and revisit the Donald Trump-era decision to remove protections from wetlands and intermittent streams. But reversing that decision could be challenging: Thirteen states sued to block the Obama-era Clean Water Rule, 17 states and several environmental organizations sued to block the Trump-era replacement (the Navigable Waters Protection Rule), and defining the protected waters of the United States has been the subject of debate for decades.

The Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers in 2019 repealed the Clean Water Rule, which clarified what bodies of water fell under federal protection from pollution under the 1972 Clean Water Act. In 2020, the agencies replaced that rule with the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, which removes isolated wetlands and ephemeral and intermittent streams from federal protection.

The rule change reduces restrictions for developers, agricultural operations, oil and gas companies, and mining companies to dredge, fill, divert and pollute ephemeral streams and isolated wetlands. According to a 2017 staff analysis by the EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers, the new rule leaves more than half of U.S. wetlands and 18% of U.S. streams unprotected, including 35% of streams in the arid West.

As they developed the rule, the EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers considered water quality as a "local public good." This runs counter to scientific research that shows that even ephemeral streams and isolated wetlands are connected to larger watersheds, meaning what happens upstream affects waterways downstream, increasing the risk of flooding, diminishing water quality, and causing other problems that don't stop at state borders. The article finds that the narrower definition of water quality skewed benefit-cost analyses in a way that favored removing regulations.

The agencies based their benefit-cost analyses on the assumption that leaving streams and wetlands unprotected won't cause any harm to water quality in many states, because those states will rush in to protect waterways as needed.

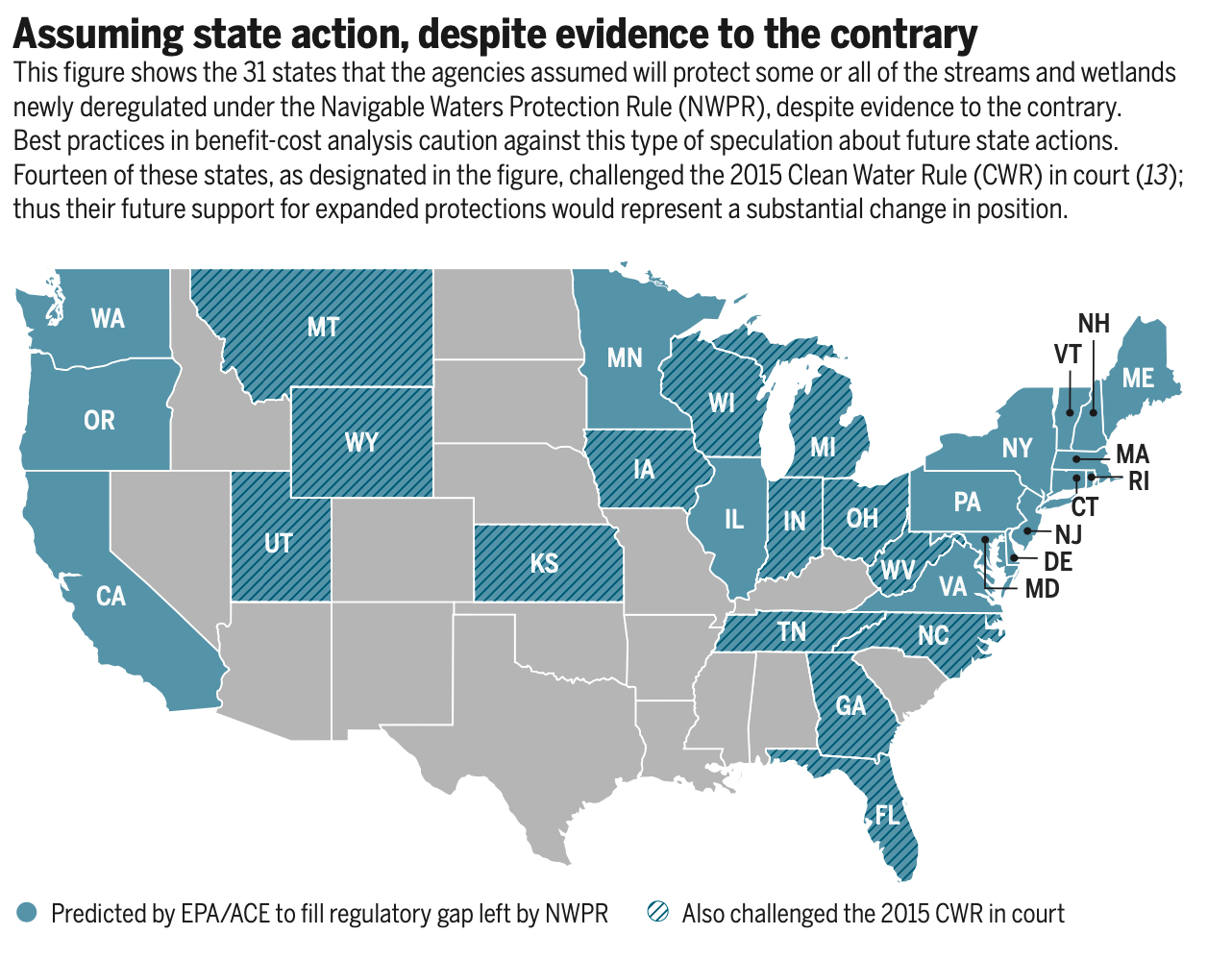

"We cannot speculate that states will fill gaps in federal oversight," said Olmstead, a professor of public affairs at UT Austin and co-lead author of the paper. "When the agencies zeroed out the benefits and costs of this action in 31 states, assuming those states would enact laws that do not exist, they violated best practices in benefit-cost analysis. The Biden administration has said it will review the practice of analyzing regulations' economic impacts, and this would be an important thing for them to look at."

The study also found that half of the states that the agencies said will protect the affected wetlands and streams sued to overturn the earlier Clean Water Rule, so these states' decisions to protect isolated wetlands and ephemeral streams going forward would be a 180-degree change in position.

The External Environmental Economics Advisory Committee, which commissioned the review that prompted the Science paper, is supported by the Luskin Center for Innovation at the University of California, Los Angeles and partially funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

In addition to Olmstead in the LBJ School, the article's co-authors are David Keiser, University of Massachusetts; Kevin Boyle, Virginia Tech; Victor Flatt, University of Houston; Bonnie Keeler, University of Minnesota; Catherine Kling, Cornell University; Daniel Phaneuf, University of Wisconsin; Joseph Shapiro, University of California, Berkeley; and Jay Shimshack, University of Virginia.