Key points:

- Feedlot input cost operating similarly to 2020 levels

- Feedlots no longer having to compete with restocker competition – allowing feeder prices to ease

- Days on feed are expected to shorten as feeder prices fall and grain prices rise.

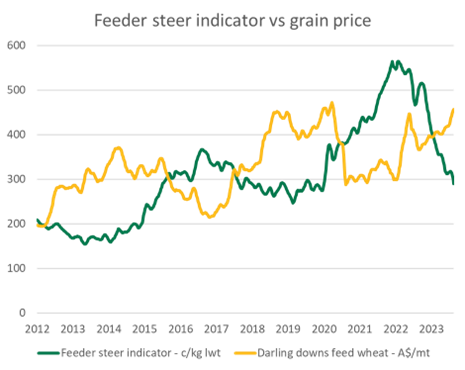

Feeder cattle and feed grain prices are usually inversely related, meaning when one increases, the other decreases and vice-versa. There are two main reasons for this.

Firstly, both these commodities react differently to weather conditions. In a drought, grain is scarce due to poor harvest yields. Whereas cattle turnoff increases during drought as producers sell cattle given the lack of available feed.

Secondly, they are the two largest cost inputs for feedlots, meaning that changes in the price of one can affect demand of the other, which in turn affects price.

The price relationship is now returning to similar levels to those last seen in early 2020. The national feeder steer price currently sits at 250¢/kg liveweight (lwt), and the Darling Downs feed wheat price sits at $465/metric tonne (mt).

Feeder steer prices were high relative to feed grain prices between 2020–2022, as the cattle herd rebuild restricted cattle supply, and strong demand from restockers meant that feedlots had to compete with more producers to fill their pens. Grain prices locally remained high but relatively stable due to good weather in crucial grain growing regions that produced record harvests.

These dynamics have partially reversed so far this year. Since January, feeder steer prices have fallen by 31%, while feed wheat prices have risen by 16%. This reflects the maturation of the national herd rebuild, increased cattle supply, and a poor harvest outlook for southeast Queensland, northern NSW, and parts of WA's Wheatbelt, pushing domestic grain prices up.

This increase in grain prices and fall in feeder cattle will likely affect future feedlot behaviour.

Between 2020 and 2022, the average time cattle were kept on feed was generally high, as feeding cattle to induce weight gain was usually cheaper than buying additional cattle. This is less true in 2023 than in 2022, so long feeding programs are becoming relatively less attractive, while shorter programs, with a superior cost of gain and less time holding cattle in a volatile market, would be more attractive.

Given that, we expect that feedlot turnoff will likely increase in 2023, while average days on feed will fall.

Attribute content to: Tim Jackson, MLA Global Supply Analyst