First, the good news: after a couple of years, most Quebecers who use a food bank for the first time will no longer need to do so. Now the bad news: 40 per cent will, and will keep coming back regularly or occasionally.

That's the finding of a study by a team of researchers from the Centre for Public Health Research (known by its French acronym CReSP), led by Louise Potvin of Université de Montréal's School of Public Health and Geneviève Mercille of UdeM's Department of Nutrition.

For the study, called Parcours, the researchers followed 1,001 first-time food bank users in Quebec recruited from 106 community organizations in four regions (Montreal, Mauricie-Centre du Québec, Lanaudière and Estrie) between 2018 and 2022.

The results were published last summer in Lumière sur la recherche au CReSP and, since then, in a number of scientific journals.

Food insecurity means skipping meals

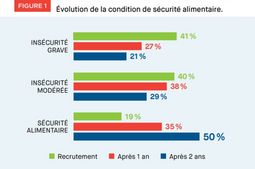

The study found that more than 80 per cent of users visiting a food bank for the first time were experiencing food insecurity, with almost half facing severe insecurity, defined as regularly skipping meals.

Seventy-five per cent of study participants had a household income of less than $20,000 per year. Their physical and mental health was worse than that of the general population. This group initially visited the food bank an average of 2.4 times per month.

The researchers identified five profiles of food bank users:

- Newly-arrived immigrants whose credentials haven't been recognized and who are unfamiliar with how things work in Quebec;

- People whose lives have been disrupted by physical or mental health problems and who have exhausted their resources (e.g. sold their investments or homes);

- Women, especially single mothers, who had been financially dependent on their spouse;

- People from backgrounds of intergenerational poverty who have faced difficult life circumstances since childhood;

- Elderly people who have been unable to accumulate sufficient savings for their old age.

The study tracked the first-time food bank users for two years and found that a third (33.1 per cent) stopped using food banks soon after their initial visit, and a quarter (24.9 per cent) gradually stopped using food banks.

But at the same time, almost a third (31.4 per cent) became chronic users, visiting food banks nearly every month, and 10.6 per cent continued using food banks occasionally, with breaks of varying lengths.

Montreal different from other regions

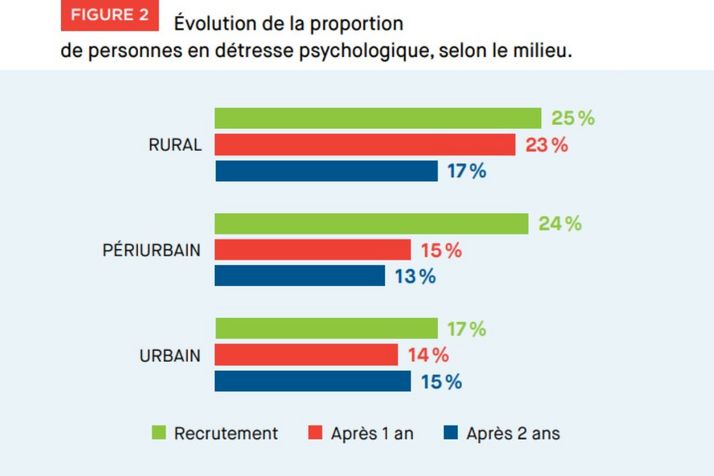

"The picture also varies by region," Potvin said. "In rural areas, among less educated people, there were more single-parent families and households experiencing severe food insecurity, whereas in Montreal there were more people from immigrant backgrounds, students and people living alone, and the level of education was generally higher."

The study found a correlation between increased income and the ability to stop getting food aid. This was true even when the higher income was still modest, in the $25,000 to $30,000 range. While only half of participants achieved food security over the two-year period, the rate of severe food insecurity decreased from 41 per cent to 21 per cent.

Prolonged reliance on food aid was associated with persistent food insecurity and deteriorating physical health.

"For people who are able to enter or re-enter the job market, food aid is a temporary support, but for very vulnerable people, such as the elderly or those with serious health problems, going back to work is virtually impossible," said Mercille.

"In these cases, getting access to social housing, getting recognition that they have a severely limited capacity for employment, or reaching retirement age are the only ways a person can improve their living conditions."

A growing concern

Statistics Canada data published in 2023 show that the rate of food insecurity in Quebec rose from 10.9 per cent of the population in 2019 to 15.7 per cent in 2022. Moderate and severe food insecurity increased from 8.9 per cent to 10.8 per cent.

"With higher inflation in recent years, the housing crisis and prevailing economic uncertainty, it is probable that an even greater percentage of people are food insecure today," said Potvin. "Community aid networks are overwhelmed and unable to meet the need."

She and Mercille believe it's important for assistance services to provide personalized support and a coordinated approach.

"A true ecosystem of support is needed, one that encompasses employability, immigrant support, women's and other social service agencies, along with broader strategies to strengthen the social safety net," said Mercille.

"When people go to a food bank for the first time, it's with a heavy heart," added Potvin. "If they have reached that point, it's because they've tried everything else and have no other alternatives. We need to continue documenting the ways in which people manage to get off food aid because food banks are not a sustainable long-term solution."

About this study

"Demande de l'aide alimentaire, et après?", by Louise Potvin, Geneviève Mercille et al., was published in the July 2024 issue of Lumière sur la recherche au CReSP.