Cryptographic systems that even quantum computers cannot crack will soon be standard in the USA

Whenever you visit a website, send an email, or do your online banking in the future, in many cases algorithms developed with the participation of researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Security and Privacy in Bochum and the Ruhr University Bochum will be used to encrypt your data. The American National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) has now announced which cryptographic methods it will standardize to protect communications from future quantum computer cyberattacks. Peter Schwabe, Group Leader at the Max Planck Institute for Security and Privacy, was involved in the development of three of the selected procedures. Most online services use the methods standardized by the NIST.

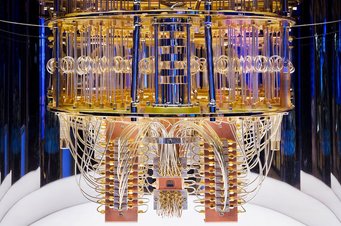

Threat to today's encryption: research institutions and companies are developing quantum computers, such as the IBM Quantum System One. As soon as the computers are as powerful as many hope they will be, they will be able to crack the cryptographic methods used in data traffic today. That is why the US National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) is already working on standardising new encryption methods. A Max Planck researcher has played a major role in three of the four candidates to be standardised.

© IBM Research

For many people - and certainly for many of the world's intelligence services - the quantum computer holds great promise. But online service providers that rely on secure data exchanges also see it as a threat. It is true that quantum computers are still being developed, and it is not yet foreseeable when the first powerful computers of this kind will come into service, but one thing is certain as Peter Schwabe, Research Group Leader at the Max Planck Institute for Security and Privacy and professor at the Radboud University Nijmegen explains: "As soon as the first quantum computers arrive, today's cryptographic protocols, which protect virtually all data traffic, will become obsolete because quantum computers will be able to solve the two mathematical operations on which today's cryptographic methods are based". They will be able to break down any large number into two prime factors in an instant. Conventional cryptography relies on prime number factorization because contemporary computers would need tens of thousands of years to do the necessary calculations and would also consume as much energy as the sun sends to the earth in the same period.

Four methods out of 69 were chosen - three with Max Planck participation

Peter Schwabe heads a research group at the Max Planck Institute for Security and Privacy. He was instrumental in the development of three of the four cryptographic methods that the US National Institute for Standards and Technology will standardize for future online communication.

© RUB, Michael Schwettmann

A total of 69 international teams from the cryptography community have submitted proposals for new cryptographic techniques to the NIST to protect data traffic against quantum computer attacks in the future - they are calling it post-quantum cryptography. After several rounds, the NIST has now decided to standardize four of these procedures because, as Eike Kiltz, professor at Ruhr University Bochum and spokesperson for the Bochum Cluster of Excellence Cyber Security in the Age of Large Scale Adversaries explains: "They will provide better protection for digital communications, because quantum computers would undermine current encryption methods and signature systems. These new algorithms show how important it is for researchers working in basic research to work together with their colleagues in the applied sciences to ensure that our data is securely encrypted in the future."

Two of the selected methods are used for authentication, namely the schemes Sphincs+ and Crystals-Dilithium, in whose development Peter Schwabe was involved: "For authentication, a signature in a so-called digital handshake ensures, for example, that a web browser is actually connected to the server it claims to be." Peter Schwabe was also part of the team that designed Crystals-Kyber and made this method fit for application. This procedure enables the secure exchange of cryptographical keys for the further communication. Amongst others, Schwabe cooperated closely with Eike Kiltz in the development of Crystals-Dilithium and Crystals-Kyber.

Post-quantum cryptography is based on mathematical operations which, given our present state of knowledge, are almost as difficult for quantum computers as they are for conventional computers. For example, both key exchange and authentication procedures use hash functions, i.e., algorithms that derive a small number from a very large input number whereby it is not possible to determine the original number from the small number, which in cryptography is called a fingerprint, which is an essential element of a digital signature.

The cryptography community is involved in the selection process

During the selection process, the NIST verified that the respective processes are secure in principle, and also whether they could be implemented in a secure and efficient manner and will now go on to write standards for the selected processes. These standards will explain the cryptographic basics and how to implement them, and will also formulate guidelines so that, for example, online service providers will be able to integrate them into their applications with comparatively little effort and, more importantly, without opening up loopholes in existing security safeguards.

Some people have reservations about the NIST's work, fearing that the agency could standardize encryption methods at the behest of the NSA, leaving backdoors open for the American intelligence service. As Schwabe admits: "We know for sure that this has happened in one case in the past". But, he adds, the authority in question presumably did not do so knowingly and has since admitted that it made a big mistake in doing so. "Unlike the current processes", says Schwabe, "the process with the backdoor loophole wasn't developed by academics, and the crypto community is now more involved in the selection process. So now it is not only the NIST that checks the potential security vulnerabilities of the available methods, but also more or less the entire global cryptography community". And, he continues, "the NIST has already framed the selection process for new cryptography standards twice as for post-quantum cryptography. And the resulting procedures have proven to be very secure and are now used all around the world."

European authorities are likely to adopt the standards selected by the NIST

So it is to be expected that the decision taken by the NIST will set the standards, at least for the USA and Europe. As Eike Kiltz, spokesperson for the CASA and one of the contributors to the proposal, says: "The new NIST standard will certainly become one of the most influential documents in IT security". Whilst the European authorities are still examining the procedures selected by the NIST, as Schwabe explains, experience has shown that, provided they do not find any security gaps, they will agree with the assessment of their US American colleagues, not least to enable encrypted data exchanges between services and computer programmes located in the USA and EU respectively. For Google, Amazon, Apple, and virtually every other company that provides online services, the need to communicate with each other is an incentive to rely on the encryption methods standardized by the NIST. "And, if security vulnerabilities do occur, they can then blame the NIST," says Schwabe, who thinks that the standardization process could be completed by the end of 2023. But some companies, such as Google and Infineon, are already trialling post-quantum cryptography alongside current standards, which are vulnerable to quantum computer attacks and car manufacturers too are already exploring post-quantum cryptography to ensure that they will still be able to reliably update the software in their current vehicles in 15 or 20 years' time without too much effort. "Our assumption", says Schwabe, "is that more and more services will use the new procedures once they have been standardized". The hope is that the encryption processes that Schwabe and his colleagues have helped to develop will then be able to make web surfing, email traffic, and banking transactions even more secure even before the first quantum computers are available.

PH